One Thing M*A*S*H Got Wrong Was Marvel Comics History

What do "Happy Days" and "M*A*S*H" have in common? Well, for one thing, they're both era-defining TV shows of the 1970s that took place in the 1950s. "M*A*S*H" was set during the Korean War (even if its satirical target was the more recent Vietnam War), which unfolded from 1950 to 1953. It's a well-known joke that thanks to its 11-season run (1972 to 1983), the series lasted longer than the war it was set in.

That's not the only historical incongruity in "M*A*S*H" — there's a small but telling one in season 4, episode 21, "The Novocaine Mutiny," as first noted in "TV's M*A*S*H: The Ultimate Guide Book" by Ed Solomonson and Mark O'Neill. In this episode, Major Frank Burns (Larry Linville) is left in command and predictably behaves like a tyrant (a la Captain Queeg in "The Caine Mutiny," the root of the episode's title). He begins searching officers' quarters for "stolen" (actually gambled) money. When he gets to Radar's (Gary Burghoff) office, he finds some comic books; the scene transition is a cut to Burns taking the comics out of drawers and stacking them one by one.

These floppy issues are only visible for a split second, but looking closely, they include copies of "Amazing Spider-Man" issue #81 and "The Avengers" issue #72. There's just one problem; the episode is in 1952, when these comics didn't exist yet.

The Marvel age of comics

Spider-Man debuted in "Amazing Fantasy" #15, published in 1962; he got a solo title, "The Amazing Spider-Man," the following year. 1963 was also the debut of The Avengers (as a team, at least) in, well, "The Avengers" issue #1. As for the specific issues featured in "The Novocaine Mutiny"? They were both published in 1969. Long story short — neither comic in "M*A*S*H*" existed until more than a decade after the Korean War had ended.

Moreover, Marvel Comics wasn't even Marvel Comics yet. The company existed, but from 1951 to 1957 (a timespan including the Korean War's duration and end), it was known as Atlas Comics. It also wasn't publishing superhero books at this time — those were largely verboten thanks to the moralistic crusade of child psychiatrist Dr. Fredric Wertham. Instead, the publisher specialized in monster and sci-fi books, taking the premises of B-movies and rendering them as eight-page stories in the funny books. Atlas Comics changed its name to Marvel Comics in 1961, which coincided with their reentry into publishing superhero stories.

By 1976 (When "The Novocaine Mutiny" first aired), Marvel Comics was fairly well-known (if still not the cultural juggernaut they are today). Grabbing a few spare issues as minor props would be easy, and it communicates to the 1970s audience that Radar is a nerd. It's still anachronistic to the world of "M*A*S*H," but it's too minor an oversight to be immersion-breaking (the comics are barely visible). It's also not a complete historical aberration.

Soldiers reading comics

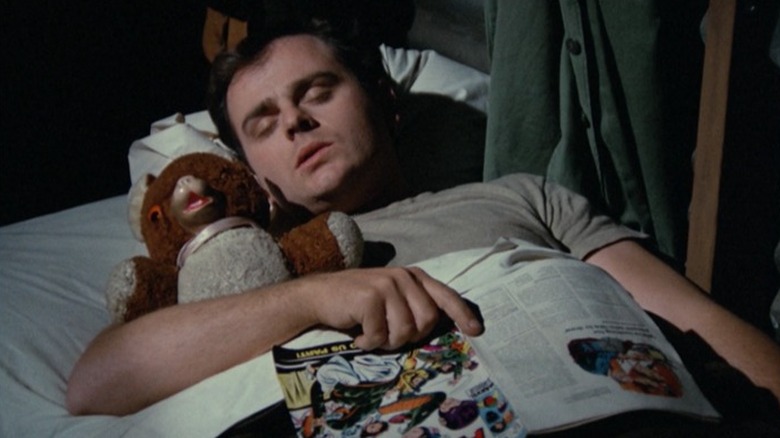

"The Novocaine Mutiny" isn't the only time on "M*A*S*H" that Radar is shown to be a comic reader. In "Der Tag" (season 4, episode 17), he's shown sleeping with a copy of "The Avengers" issue #60 (published in 1968) ... though in a later shot, it changes to issue #72 (probably the same copy then used as a prop for "The Novocaine Mutiny").

While the timeline doesn't add up, "M*A*S*H" is right about one thing; during the 20th century, comic books were read by American soldiers overseas. It goes back to World War II; after all, superhero comics took off in 1938 with the creation of Superman, a few years before America entered that conflict. In 1940, Jack Kirby and Joe Simon (two Jewish boys from Brooklyn) created Captain America in support of anti-Nazi sentiment; there's a reason Cap's first appearance has him punching Adolf Hitler.

Once the U.S. entered the war in 1941, they started shipping comics to their soldiers fighting overseas. After all, comics were cheap (so easy to buy in bulk), while for the soldiers, they were escapism, even easier to read than pulp novels, and disposable. Comic creators understood their audience, so the contemporary adventures of Captain America, Wonder Woman, and Superman were patriotic, with Nazi villains and support for the war effort.

Not everyone who wears a cape is a hero, but everyone who punches Nazis is.