Charlie Chaplin Vs. America Review: The Detailed Chronicle Of A Real-Life Hollywood Rise And Fall

Author Scott Eyman is the foremost chronicler of Hollywood's first century, with 16 nonfiction books to his name. His previous book, "20th Century-Fox: Darryl F. Zanuck and the Creation of the Modern Film Studio," was a "biography" of the titular studio. With his latest, Eyman narrows his focus again to a particular star – one of Hollywood's first, in fact: Charlie Chaplin.

"Charlie Chaplin vs. America: When Art, Sex, and Politics Collided," published on October 31, 2023, is titled as such because it was that collision that got Chaplin exiled from his adopted homeland. His enemies, who included the FBI, Senator Joseph McCarthy, and Tinseltown columnist Hedda Hopper, branded him a communist (he was not), Anti-American (also false), and a sexual deviant (on that one ... they had a point). An English immigrant who'd never bother becoming a citizen of America, his U.S. re-entry permit was stripped in 1952 and he and his family lived out his remaining 25 years in Switzerland.

Eyman's experience chronicling Hollywood is an asset in providing a cumulative view of this story. "Chaplin vs. America" offers an extensively researched inside look at these events and Chaplin's soul. Eyman makes it clear his position is pro-Chaplin (he closes his prologue with the sentence, "It's time to see Charlie clear"), but he writes as a journalist, not an evangelist.

Woven in through Eyman's writing and framing are countless quotes from people who knew Chaplin offering their thoughts on the man (the concise ninth chapter is largely an unflinching summation of Chaplin by his friend Tim Durant) — not to mention from the man himself. This gives the book a personal touch and objective framing; the reader can absorb first-hand accounts from people within their proper context and draw their own conclusions about Mr. Chaplin from them.

A biography worthy of Chaplin

"Charlie Chaplin vs. America" is structured like many biographies (or biopics). It opens in media res when Chaplin has his re-entry permit taken away in 1952, then stretches back to explain how he got to that point.

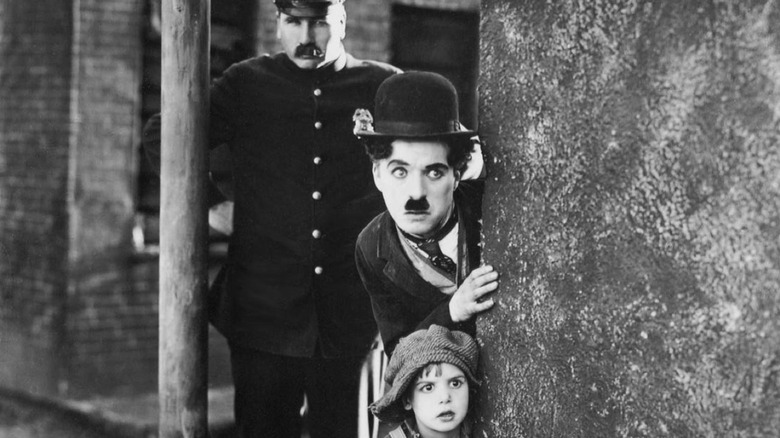

The book covers its subject's early life — Chaplin's poor childhood in England with his brother Sydney, his touring with the Karno company, making his way to America and then stardom — but marches through it in about 80 pages. The remaining 270 are focused on Chaplin's later life, not his silent movie heyday as The Tramp, and it's his post-"Modern Times" films that get the most attention and critical analysis.

Those later films, after all, represent the goalposts of his peak and decline: "The Great Dictator" (the film that got the Right thinking Chaplin might be a Leftist, not just an antifascist), "Monsieur Verdoux" (a flop and sign the public had turned against him), "Limelight" (semi-autobiographical and his failed attempt to win back public support via emotional honesty), and finally "A King in New York" and "A Countess from Hong Kong" (both fish-out-of-water stories, made in Europe during Chaplin's exile).

"Charlie Chaplin vs. America" is not lean in sheer page count, but it is in its storytelling. There's not a wasted word and if the book ever lingers, it's only to add useful context — for instance, why Eyman feels "Modern Times" and "The Great Dictator" are the most enduring of Chaplin's filmography, while "Monsieur Verdoux" was an indecisive misstep — or amusing anecdotes. (Did you know Walter Matthau's expression at the end of "The Taking of Pelham One Two Three" is an imitation of his son's own imitation of Chaplin?)

Chaplin, communist?

The book describes Chaplin as both "[potentially] the single most important figure in motion picture history" and the greatest victim of the Red Scare. How did one become the other? Eyman believes it was inevitable, for Chaplin always marked himself as an outsider, even onscreen. As an immigrant, he was bound to be othered by nationalistic Americans, and this escalated as Chaplin refused to become an American citizen (he disliked patriotism of all sorts and saw himself as a citizen of the world) or refute rumors he was Jewish (apparently he felt the latter would be playing into the antisemites' hands).

As for the man himself, Chaplin was apolitical, though not in the modern, ignorant sense. Rather, he was "too much of a free-thinker for politics" (the book cites people who described him both as an anarchist and a libertarian) and didn't wish to be tied down to any ideology, party, or nation. His principles were self-rooted: A fear of poverty, yearning for artistic freedom, and simple empathy for people who lived under society's boot as he had as a child. Thus, he hated authority, especially authoritarians like Hitler or Hynkel; Eyman notes the closing speech of "The Great Dictator" is Chaplin espousing the gospel of our better angels, a call for "evolutionary change" away from hatred.

During World War II, Chaplin saw the Soviet Union as true allies against fascism — not "enemies in waiting" as the American Right did — and made public speeches in support of their war against Hitler's Germany. Rumors swirled he was a communist, especially since he sometimes employed some (such as Rob Wagner) or kept their company, and the FBI investigated him as such. Conservative lawyers, politicians, and journalists were all too eager to play their part in the anti-Chaplin crusade, too.

'A sexual libertarian'

The book repeatedly points to Chaplin's wealth as self-evident proof against him being a communist, as Chaplin himself also did. To be sure, Chaplin spent his time in Switzerland mostly in the company of other celebrities. For as much as Chaplin stood with the little guy onscreen, his childhood spent in "the horror of poverty" left him determined to never fall into it again. It's inferred his desire for control influenced his art, making him a star, auteur, and mogul (he co-founded the studio United Artists) all in one.

However, not all of Chaplin's enemies despised him as only a "Red" in disguise. Hopper, though a conservative and House Un-American Activities Committee collaborator who counted Richard Nixon as a friend, was just as disgusted by Chaplin's ephebophilia.

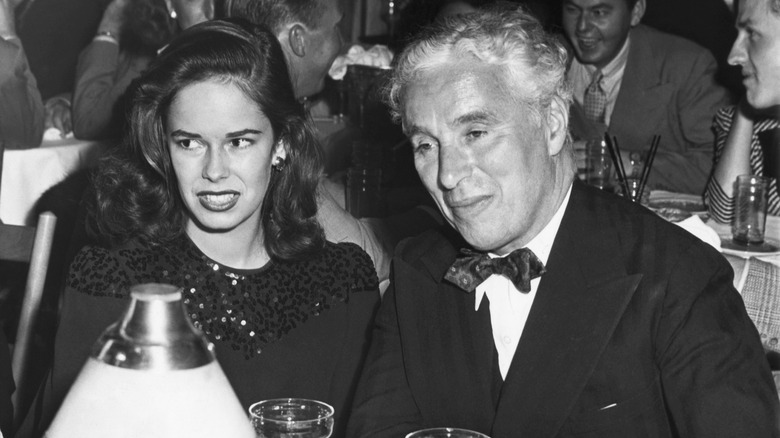

In 1943, Chaplin was the subject of a paternity suit by his former muse Joan Barry (31 years his junior) and found legally to be responsible for her child, despite a paternity test proving he wasn't the father. Reading Eyman's account of the lawsuit, it feels like Chaplin's moral character is what was on trial. Chaplin, evidently unable to help himself, also married his fourth and final wife Oona (daughter of Eugene O'Neill) that year — she was 18 and he was 54. Despite that, Eyman's book refers to this marriage as a happy one that kept Chaplin semi-contented during his twilight years; his final role was a doting husband. The book concludes that Chaplin felt his love-hate relationship with America was worth it for the chance to meet Oona. Looking in from the outside, though, it's certainly understandable why some would frown on their relationship.

A canceled star

Speaking of a modern lens, "Charlie Chaplin vs. America" has been advertised as a story about early "cancel culture." I, for one, was worried the book would make the false equivalence of comparing modern "canceling" with the truly life-destroying consequences of the Red Scare or outright defend Chaplin's fetish for young girls as overblown indiscretions. I'm relieved to say this is not the case.

Outside of a few allusions, the book is far more concerned with history than the present; though one can draw a line between how the press shaped the public perception of Chaplin to the post-truth flow of information today, the book leaves doing so in its readers' hands. Eyman's declaration in the prologue that "Charlie Chaplin had been canceled" reads more sardonic with the benefit of hindsight.

When you finish "Charlie Chaplin vs. America," you probably won't have many lingering questions about what the book sets out to answer, but you'll be tempted to watch Chaplin's films with a new eye and deeper understanding of the man who made them. As Eyman writes in his epilogue, "There has only been one Chaplin."

"Charlie Chaplin vs. America: When Art, Sex, and Politics Collided" is available at bookstores and digital retailers through Simon & Schuster.