Unforgiven Ending Explained: Deserve's Got Nothing To Do With It

Nearly 30 years after its release, 1992's "Unforgiven" remains the benchmark by which other revisionist westerns are judged. It's a movie that even its prolific director and star, Clint Eastwood, has never quite topped as a filmmaker, although his most recent offering, "Cry Macho," made for a surprisingly decent thematic epilogue to the brooding, melancholic tale of William Munny.

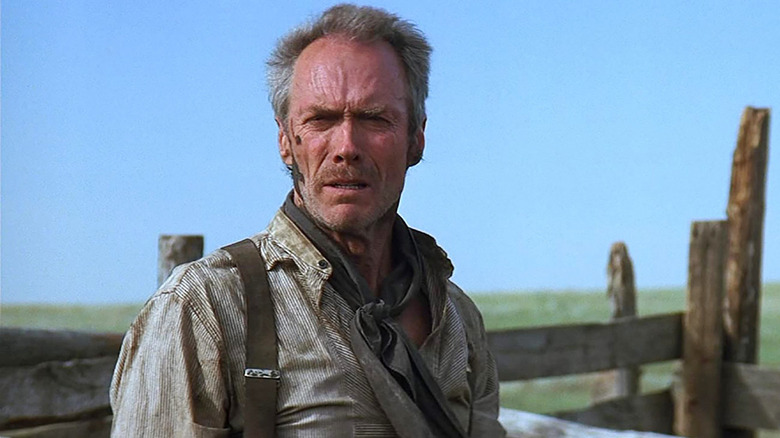

Munny, as played by Eastwood, is an aging former outlaw who's living as a humble Kansas hog farmer and raising two kids when "Unforgiven" begins in 1880. The meta nature of this casting has never been lost on anyone; Eastwood famously made his name playing morally flexible (if not outright unscrupulous) cowboys in the 1960s and '70s, most notably in Sergio Leone's spaghetti westerns. Yet, even by his standards, Munny is a violent man, having killed "just about everything that walks or crawled" (as Munny puts it during the film's climax) before he gave up drinking alcohol and settled down with the help of his late wife.

Simple redemptions and happily-ever-afters don't exist in the Old West of "Unforgiven" either, as Munny comes to realize when his farm begins to fail. Driven to do right by his children, he reluctantly recruits his old friend Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman), a fellow ex-outlaw, to join him and a young gunslinger who goes by The Schofield Kid (Jaimz Woolvett) to collect a bounty for the deaths of two ranchers who attacked and disfigured a sex worker in the small town of Big Whiskey, Wyoming.

A World of Grey Hats and Deceit

In many westerns made before the 1950s, heroes wore white hats, and villains wore black hats to reflect their intentions. Tellingly, out of Munny and his allies, only the boastful, naive Schofield Kid adheres to this tradition. Munny and Ned, on the other hand, wear brown hats, as does Big Whiskey's sheriff, "Little Bill" Daggett (Gene Hackman).

Even without any literal "grey hats," the subtext in "Unforgiven" is clear: things aren't so black-and-white in the film's setting. Neither Munny nor Ned are the heartless monsters their reputations suggest, nor is Little Bill someone to admire, as the movie establishes when he viciously beats his old rival, English Bob (Richard Harris). But as much as Little Bill knows the dirty truth about the lies and exaggerations that Bob and his kind like to spin about their exploits, he fails to see through his own delusion: that he's a noble lawman shaping Big Whiskey into something better (an idea he feels is symbolized by his building his own house).

The deceit doesn't begin and end with the men, either. Delilah Fitzgerald (Anna Thomson), the sex worker whose face was permanently damaged, didn't suffer the grievous injuries that others are led to believe, yet her peers spread the rumor, knowing it's the only way to get anything close to the justice Little Bill denied them when he let Delilah's assailants off easy. They can only afford to be as decent as the men around them allow.

"It's a Hell of a Thing, Killin' a Man."

When the time comes to shoot Delilah's attackers, Ned realizes he's no longer capable of killing other people, forcing Munny to step in and slay one of the men for him. While Ned flees, Munny and The Schofield Kid then track down their other target, with the latter ambushing and shooting him while he's in an outhouse. It's an inglorious, horrible reality compared to whatever fantasy The Schofield Kid imagined, prompting him to admit to Munny that he never killed anyone before that and give up the gunslinger life when the pair receive their reward.

For Munny, however, fleeing isn't an option when he's told Little Bill learned his identity after catching and torturing Ned to death. This is also when he finally drinks alcohol for the first time since his wife died, to steady his nerves for what needs to be done. Tonally, though, his action is presented as a moment of failure (which it is), not triumph.

Likewise, Munny's final showdown with Little Bill is anything but a battle with honor. Instead, he catches Little Bill and his crew off-guard in the local saloon at night while they're preparing to hunt him and The Schofield Kid the next morning. Munny then calmly shoots the saloon's unarmed owner before taking down Little Bill's posse and wounding Bill. When a disbelieving Little Bill insists he doesn't deserve this humiliating fate, Munny coldly replies:

"Deserve's got nothing to do with it."

What the Ending of Unforgiven Means

Munny's retort acts as a thesis statement for "Unforgiven," a film that argues the wild west was an unjust place where might made right and that those who walked away from gunfights weren't, per se, decent or even expert marksmen but the ones who could keep their cool. It was far from the first western to de-glamorize the genre and its typically romanticized portrait of America's past, but it meant something coming from Eastwood: a Hollywood icon who came to fame starring in films that glorified the violent Old West, purposely or not.

"Unforgiven" doesn't pull any punches making this point, even after Munny delivers his iconic line. When Little Bill fires back, "I'll see you in Hell, William Munny," Munny merely growls, "Yeah," before shooting him dead and making his way out-of-town, warning the locals he will return to kill them if they don't give Ned a proper burial or harm any sex workers again. He then vanishes into the cold, rainy night, looking more like a specter of death than a righteous avenger whose actions solved anyone's problems but his own.

The film's epilogue thereafter closes with a mournful shot (accompanied by Lennie Niehaus' equally sorrowful main leitmotif) of Munny standing aside his wife's grave. And while on-screen text mentions rumors that Munny later prospered in dry goods, everything about this scene suggests this glimmer of a "happy ending," like the myths of the wild west, is surely some kind of lie.