The War Terry Gilliam Fought Over The Ending Of Brazil

"But I'm not guilty," said K. "there's been a mistake. How is it even possible for someone to be guilty? We're all human beings here, one like the other." "That is true" said the priest "but that is how the guilty speak" –Dialogue from Franz Kafka's "The Trial"

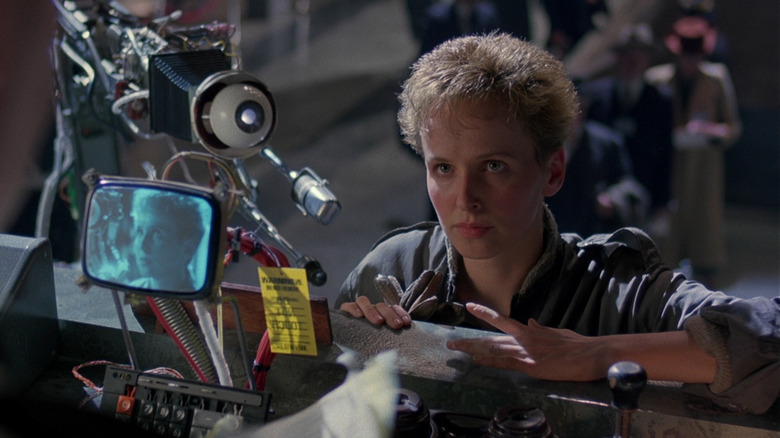

Terry Gilliam's 1985 film "Brazil" is frequently compared to the works of Franz Kafka. In "Brazil," Jonathan Pryce plays a pencil-pushing office wonk trapped in a red tape labyrinth so complicated that even the minotaur has starved. The System — a character unto itself, represented by a rotating bevvy of soulless, smiling office drones — demands conformity and refuses to acknowledge error; when someone is arrested and killed because of a mistyped document, there is no way to demand justice. There are armies of protestors and resistance fighters operating outside the system (represented by Robert De Niro), and when a terrorist attack strikes the scene of a posh restaurant where the wealthy canoodle, the wait staff merely sets up screens so that the diners need not look. Pryce fantasizes of escape via dreams wherein he is a flying White Knight rescuing a Damsel in Distress from an evil giant. By the end of the film, just like in a Kafka story, the main character has been swallowed by the System, unable to escape its dark automation or demand for a bureaucratic blood sacrifice.

An unhappy ending is the logical ending for a film like "Brazil." As anyone who has visited the DMV or anyone who has tried to call the IRS knows, bureaucracy is a creature unto itself, a blind, hungry octopus that feeds on stress and demands to memorization of senseless, convoluted rules that have no place in logic. Boldly standing up to bureaucracy will only lead to misery and death.

In a grand sweep of ultimate irony, Gilliam's story of a bureaucracy run amok would, itself, become mired in bureaucracy.

The release

Gilliam was in production on "Brazil" throughout 1984, and one of the working titles of the film was "1984 1/2," alluding to both Orwell and Fellini. Wanting to tap into the spirit of Orwell's 1948 dystopian novel, Gilliam ideally wanted "Brazil" to land in theaters that year, hoping to invite comparison. Gilliam submitted a 132-minute cut of "Brazil" to Universal Pictures, complete with a very tragic ending wherein (and not to give too much away) the Pryce character triumphs over the machine, but only in his mind. The plan was to release "Brazil" in Christmas of '84, but Gilliam realized he had to re-write his script, as it was getting too complicated. Even though production shut down for several weeks — ensuring a delay in release — Gilliam still submitted his completed film under budget.

Universal, reportedly, did not like Gilliam's cut and simply sat on the movie for a longer time than expected. Universal head Sid Sheinberg demanded a shorter cut and a happier ending. Gilliam said he'd be happy to release Sheinberg's cut ... if he took his name off the film. Gilliam recapped the conversation thus: "'Listen, Sid, the film we made is the film we all agreed to make. If you want to make another film, you have my support. Just put your name on it. 'Sid Sheinberg's Brazil.' Very simple." This conflict between Sheinberg and Gilliam only cause more delays. Gilliam, upping the antagonism, also infamously put out ads in Variety demanding that Universal release his film already.

Sheinberg and Gilliam became increasingly acrimonious over the course of the year, giving conflicting interviews, threatening legal action and, at one point, Sheinberg threatening to sell the movie to another studio for a pittance. Gilliam, in a fit of rebellion, started screening the movie himself. An unnamed collaborator — Gilliam has always been coy as to their true identity — hosted screenings of "Brazil" in their Beverly Hills mansion, allowing critics to see and write about "Brazil." When LAFCA declared "Brazil" to be the best film of 1985, Universal finally released the film to the public ... but wanted it cut to 94 minutes.

The three versions

The version of "Brazil" audiences got to see was different from the one that LAFCA had called the best film of 1985.

The version Gilliam showed to critics was his own cut that ran 142 minutes. This was also the version released into international markets, and was being handled by 20th Century Fox, who had no issues with a long, bleak movie. Universal, meanwhile, was working on the 94-minute version without Gilliam's input. Now dubbed the "Love Conquers All" version, the 94-minute film had cut many key scenes, removing elements of the film's darkness, and excised an ending that made clear the dark fate of the Pryce character. The Love Conquers All version only featured a triumph over evil and a placid dream of an ending where everything worked out for the main characters.

Gilliam, meanwhile, began to capitulate, and, after "Brazil" had received its critical acclaim, started shaving down his own version, trying to tighten in to the best of his abilities. Universal suggested that they test both the Love Conquers All version and Gilliam's version, but Gilliam refused. Eventually, Universal — begrudgingly — released a 132-minute version of "Brazil." It was finally free. The 94-minute version still snuck its way out there, used for television broadcasts. As far as I have been able to discover, Gilliam has never seen "Brazil" on network TV.

The fight, won

"Brazil" went on to be an enormously celebrated and inspirational film. The works of Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro are clearly influenced by the blustery chaos of "Brazil," and most urban dystopian nightmares owe it a debt, from "The Hudsucker Proxy" and "Dark City" to "Super Mario Bros." and "Meet the Hollowheads." Gilliam even appeared in "Jupiter Ascending" as a pencil-pushing notary with a coveted notarizing stamp, a nod to his most famous film.

Gilliam would continue to make movies, although almost each one of his films has been beset with horrendous production problems. For Universal, he would make an adaptation of Hunter S. Thompson's book "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas," with a conflict as to which version of the script was to be used. Alex Cox ("Repo Man") wrote an unused draft, but was still a credited screenwriter. The trials of making an unfinished "Don Quixote" film are detailed in a 2002 documentary called "Lost in La Mancha" (although Gilliam would eventually finish that film ... in 2018). "The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus" saw the untimely death of its lead actor.

"Brazil," however, has been given the A treatment for years. In 1999, The Criterion Collection put out a 5-disc Laserdisc set will all three cuts of the movie, followed by a three-DVD, and a Blu-ray which all exhaustively talk about the battle over the film, the hot attitudes behind the scenes, and the ultimate decisions that led to Gilliam's final cut.

Gilliam has renounced his American citizenship, and now, at age 81, lives in Italy.