Ferrari Ending Explained: Time Trials

Throughout his 40-plus year career, filmmaker Michael Mann has accumulated and proliferated many colorful phrases and bite-sized poetic philosophy. One of his most favored (turning up in his director's cut of "Manhunter" and, most notably, his film version of "Miami Vice") is the phrase "time is luck." The sentiment refers to how every second one can breathe — to ambulate and interact with the world around them, to manipulate and change it and, in turn, be changed by it — is an opportunity and a blessing.

Mann's personal and professional philosophies were heavily influenced by his time researching and befriending men who operated on both sides of the law, and he found that law enforcement officers as well as lifelong criminals tend to have an innate sense of a ticking clock in their lives. While the bulk of Mann's filmography deals with cops, criminals, and crime, there are several notable outliers — "The Keep," "The Last of the Mohicans," "The Insider," and especially "Ali" — that point the way to his latest film (his first in eight years!), "Ferrari."

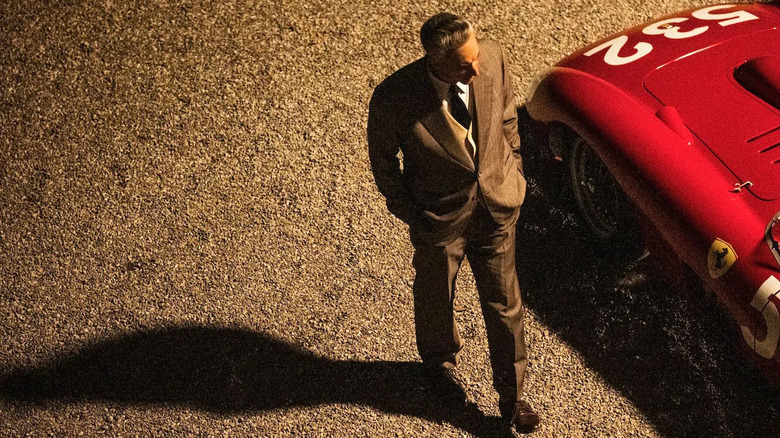

Although Mann's no stranger to telling stories about real-life figures (even "Heat" was based on the actual exploits of Chicago cops and criminals), he's never made a capital-B Biopic before, tracing a person's life from the cradle to the grave. Instead, he enjoys hyper-fixating on a specific section of someone's personal history, and "Ferrari" is no exception. This is no mere reflexive artistic tic, however — the events of 1957 in the life of Enzo Ferrari (played by Adam Driver) are shown by Mann and writer Troy Kennedy Martin (based on the 1991 biography "Enzo Ferrari: The Man, the Cars, the Races, the Machine" by Brock Yates) to encapsulate the near-totality of the man, his ambition, and the way he was seemingly haunted by death. Or, put another way, lost time.

The haunted mansion

For those who only know about Enzo Ferrari casually, the existence of "Ferrari" may seem odd on the surface. After all, most movies about the sport of racing — "Grand Prix," "Le Mans," "Days of Thunder," and even "Ford v Ferrari" (which Mann co-executive produced) — focus on the drivers, not the owners.

"Ferrari" explains this potential confusion directly from the cold open, which depicts a young Enzo in his days as a race car driver during the 1920s, the footage treated to look like it was taken during that era. With this elegant opening, Mann announces that "Ferrari" is indeed a movie about a racer; despite that part of his life being behind him, it's clear that his mentality was formed from his days behind the wheel.

The bulk of the film takes place in Modena, Italy in 1957, a decade after Ferrari and his wife, Laura (Penelope Cruz) founded Ferrari S.p.A. 1957 also marks the first anniversary of the death of Laura and Enzo's only son, Alfredo aka Dino, who passed away in 1956 from muscular dystrophy. As a result, all is not well in the Ferrari household. Make that two households: Enzo spends half his time with the mistress he loves, Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley), and their own son, Piero (Giuseppe Festinese). When he does go home to Laura, the two either bitterly discuss business, as Laura has been made owner of half of the company, or fight explosively about the loss of their son and their relationship.

Each parent deals with the still-painful loss in their own way. Enzo visits Dino's grave every day, weeps, and moves on, rushing headlong into business and preparing his racing team. Meanwhile, Laura moves like a ghost haunting her own life, visiting Dino's grave separately from her husband. Upon seeing Enzo return from spending the night with Lina, she angrily fires a gun at him. Enzo believes she deliberately missed, but Enzo's mother Adalgisa (Daniela Piperno), who lives in the eerie mansion with the married couple, isn't so sure.

Time's up

In the way he prioritizes his cars and his racing victories over his personal life, it would initially seem that Enzo Ferrari is a typical "great man" of sport and business, someone whose ambition outweighs his morality. Yet Mann doesn't allow for a reading that simple or easy, as early in the film, Enzo and his men attend Mass while the racing team for Maserati is testing their new car on a nearby track.

As the Mass begins, the priest delivers a sermon that deliberately compares the car engineers to Jesus, making the audacious claim that if Jesus were alive, he'd be making race cars himself. Later, while the Maserati is being tested, Enzo and his men pull out their stopwatches while still in church, keeping an eye on the lap time that the car is making so that they know what to beat.

Armed with the knowledge of the new Maserati's impressive lap, Ferrari and his crew rush to the test track, pushing their new car and their best driver, Eugenio Castellotti (Marino Franchitti), to beat the Maserati's time. As the test is underway, Ferrari is once again hounded by an aspiring driver, Alfonso de Portago (Gabriel Leone), who had earlier solicited Ferrari during the latter's rush home from Lina's. Ferrari tries to dismiss the man, only to see Castellotti lose control of the car and careen out of it, flopping like a rag doll on the hard pavement below. "Call my office Monday," Ferrari tells Portago matter-of-factly, the other driver's death seemingly barely registering. As Enzo explains to Piero later, his mission is to make the engine go faster by switching out this part for that one, something Ferrari clearly does with people as well as machines. And if God is on his side like the priest implies, why shouldn't he?

The Mrs. and the mistress

Ferrari's penchant for switching out parts that are no longer efficient for those that are is not lost on either of the women in his life. Although he openly loves Lina and she loves him, the woman is beginning to feel the pressures of being the mistress of such a publicly married man, not the least of which being that her son's confirmation is approaching and Ferrari is still stalling on whether or not to give the boy his name officially. Unlike Enzo and Laura, Lina is not an ambitious person and understands the thorny situation she's gotten herself into. Yet she believes in fairness, especially when it comes to Piero's welfare.

Meanwhile, Ferrari's relationship with Laura is certainly fraught and fractured, but it's not completely broken. During one heated argument, the couple ends up having sex spontaneously. Though their lovemaking is far from tender, as the two use their bodies as an extension of their feud. Where Lina is prone to make impassioned pleas to Enzo's better nature, Laura has become ruthless; while Enzo is busy, she tracks down Lina's home, swiping a toy race car from the house's stoop that Piero had left there earlier.

Upon being told that Ferrari S.p.A. is on the verge of bankruptcy, Enzo realizes that he must make advances to other investors to save the company, but is powerless to make a full on-the-fly deal when he only owns half the company. Ferrari explains the situation to Laura, hoping she'd give back her half. Laura, armed with her new knowledge of Piero and Lina and blaming Enzo for not using his bullish ambition to save their son's life (which Enzo vociferously denies, of course), makes a deal: she'll give him power of attorney, but only if Enzo will write her a check for half a million dollars. "This is a gun to our head," Enzo remarks after agreeing, knowing that if she cashes the check before a deal goes through, the company will be dead.

Pressing the flesh

Despite not being behind the wheel of one of his race cars, Enzo Ferrari is shown to be just as competitive and ruthless as he tells his drivers they should be. Literally; during a post-race meeting, Enzo chastises his drivers, including de Portago and Piero Taruffi (Patrick Dempsey), for being too sportsman-like in their attitudes. He closes his speech by acknowledging the danger inherent in racing, admitting that death is beyond mere possibility for them, and is practically inevitable.

The younger de Portago has not lived through such tragedies as Ferrari has, however, and is idealistically in love with his fame, his position, and especially his actress girlfriend, Linda Christian (Sarah Gadon). Initially, Ferrari demanded that de Portago keep his public relationship with Christian out of the limelight, wishing instead that the cars be front and center in the media. de Portago essentially disobeys Enzo in this regard, yet Ferrari does not seek reprisal. On the contrary, he pointedly moves Christian into press photos with himself and de Portago, using the duo's tabloid fame to draw more attention to his company.

This is all because Enzo realizes he needs every bit of attention he can get to bring a financier into the company. Following that line of thinking, he bribes a journalist to plant a story about his speaking to Henry Ford about coming on board as a partner, despite it being a total fabrication. As payment, Enzo promises the writer an exclusive on his personal life, willing to sacrifice Enzo Ferrari the man for Ferrari the corporation. It works; soon after the story is published, Ferrari is contacted by the head of Fiat S.p.A., foreshadowing the eventual merger of the two.

Crash course

As Enzo Ferrari comes to understand, the bigger the victory means the bigger the price is to be paid. Initially, he believes he's only offering up his own money, his own public image, his own soul, and that of his family on the chopping block. He even sees his drivers as an extension of himself, pitting them against each other and casually gassing up (literally and figuratively) each man as he sends them off on the 1957 Mille Miglia (translation: Thousand Miles), an open-road race begun in 1927.

As the race runs its course, it becomes apparent why 1957's Mille Miglia will prove to be the last of its kind. At first, a few minor mishaps occur: a couple of cars are run off the track, resulting in debilitating damage to the vehicles but little to no damage to their drivers. However, on one particular straightaway, de Portago's front tire explodes (most documentation about this event simply states that the tire blew, while Mann makes a point of showing that de Portago hit an object in the middle of the road, slashing the tire and causing its explosion). As a result, de Portago flies out of his vehicle to his death, and his car careens violently through a nearby crowd, killing nine people, including five children.

Ferrari is adamant that the incident was an accident and/or due to driver error, yet even he seems shaken by the sudden and large loss of life. When one of his mechanics grimly yet practically intones "We all know death is nearby," he counters: "Children don't. Families don't." Once again, Ferrari feels responsible for the death, especially since children were involved, yet his public reaction is anything but contrite. He rails at the Italian press, who are only too happy to vilify him, and he, martyr-like, accepts their ire.

Clearing the heir

Ferrari is at least able to find solace in the arms of Lina, something he's pushed to do as Laura has already ordered him to move out. Yet his future is still in jeopardy, as not only has the tragic crash made him infamous for the wrong reasons, but he discovers that Laura has cashed that check for half a million, essentially bankrupting Ferrari S.p.A.

When Enzo confronts Laura, he believes that his wife has enacted her most damning punishment, taking the money she feels she's owed after her own loss and mistreatment. To his surprise, however, Laura is far less petty than he thinks: she gives him the money back, telling him to use it to pay off certain journalists who will help reestablish Ferrari's good name so that Enzo can make a successful sale of the company.

Laura initially tells Enzo that her offer of the money is unconditional, yet she does have a request (as opposed to a condition or demand): that Ferrari not give Piero his name until after her passing. Again, this seems like some revisionist history on the part of Mann, Martin, and (possibly) Yates, as the generally accepted reason for Piero not taking the Ferrari name is that divorce was illegal in Italy until 1975, and Laura died in 1978. "Ferrari" not only gives a more Shakespearean reason for the late name change but implies that neither Laura nor Enzo were ready to acknowledge the future yet; they were both still haunted by the past.

Left behind

Legacy is something that the Ferraris clearly struggle with, openly wondering whether those who've been left behind deserve to remain. Early in the film, Adalgisa pulls a "Walk Hard," reminiscing about Enzo's older brother, Alfredo (who died in 1916 of flu), exclaiming that "The wrong son died." That sentiment weighs heavily over the film's final scene, as Enzo meets Piero outside Dino's grave. Adding to the specter of death that hangs over the moment, Enzo hands Piero the autograph of de Portago that Ferrari managed to get for his son just before the driver's fateful race days earlier.

As Enzo begins to bring Piero to "meet" his deceased brother, the mood feels less somber and more matter-of-fact, as if they were going to literally speak with a still-alive Dino; which makes it all more ominous. Enzo's final words of the film, telling Piero about Dino: "I wish you could've known him. He would've taken you with him everywhere." Is Enzo fantasizing about a world where Dino is still alive and could be a proper brother to Piero? Or is Enzo so fatalistic after the events of his life (not to mention the recent crash) that he has some sort of death wish for himself and his son, so that all of his family could be together in the afterlife?

If the sport of racing is typically seen as a willful flirtation with death, "Ferrari" is a film that takes the more unusual stance that being a racer is like being married to death, and not just some mere dalliance. Legacy and mortality hang heavy throughout the movie, especially as Mann dedicates the film to director Sydney Pollack (who passed away in 2008, eight years after he and Mann discussed collaborating on the project) and screenwriter Martin, who himself passed away in 2009. Like the most recent work of some other filmmakers of his generation — namely Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese — Mann knows that the end is nearer now, and is exploring those fears and emotions through his film.

More than ever, he understands that time is luck, and for Dino, for de Portago, for Ferrari, for everyone, eventually, luck runs out.