Blade Runner's Ending Wasn't The Only Reason Harrison Ford Hated His Voiceovers

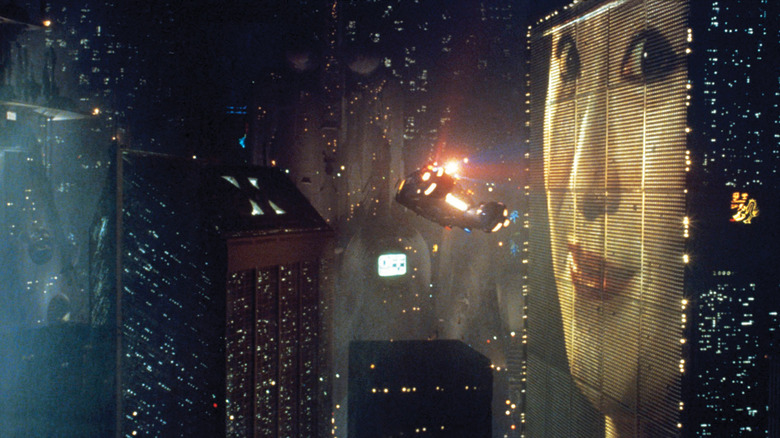

When "Blade Runner" was released in June of 1982, the response of both audiences and critics was less than adoring. Despite garnering $6 million on its opening weekend, the film eventually fell off the map, thanks in part to scathing reviews like this one from Roger Ebert: "I suspect my blender and toaster oven would just love it." It also didn't help that Steven Spielberg's "E.T." had also been released just two weeks prior, causing fans to compare the family-friendly tale of an alien trying to get home with a confusing dystopian adaptation about something called "replicants." It wouldn't be until the '90s that "Blade Runner" would enjoy a revival, inspiring a future generation of filmmakers like Christopher Nolan and Denis Villeneuve.

As for the reason for its initial flop, the answer changes depending on who you ask. Ask director Ridley Scott, and he'll point out that the theatrical cut of the film was never his intended vision (something remedied with his 1992 director's cut). But if you ask actor Harrison Ford, who plays Rick Deckard in both the original and in Villeneuve's sequel "Blade Runner 2049," you'll get a slightly different answer: One that expresses his eternal distaste for not just his voiceovers (which appeared in the theatrical release), but also the inclusion of a happy ending that was incongruous with the rest of the film.

An ode to noir gone dull

When Scott first saw his original cut of the film, he seemed to sense its indiscernible nature. "I think it's marvelous," he reportedly told editor Terry Rawlings according to Vanity Fair, before asking: "But what the f*** does it mean?" This cut of the film (sans voiceovers and happy ending) was screened in Denver and Dallas to audiences who reflected Scott's inquiry in a less enthusiastic way. After the lukewarm reactions due to confusion over the plot, a decision was made to insert all voiceovers into the movie. Although clearly a nod to the noir genre that helped inspire and inform Scott's film, Ford found the lines in those voiceovers less than ideal, calling them "awkward and uninspired." In an interview with Playboy in 2002, the actor elaborated further:

"I was compelled by my contract to do the narration. When I first agreed to do the film, I told Ridley there was too much information given to the audience in narration. I said, 'Let's take it out and put it into scenes and let the audience acquire this information in a narrative fashion, without being told it.' And he said it was a good idea. We sat around the kitchen table and we did it. When we got done, the studio said nobody will understand this f***ing movie. We have to create a narrative."

In a beautiful turn of irony, once the executives actually saw a cut of "Blade Runner" with the voiceovers, they realized just how big of a mistake it was to have put them back in the movie. Vice got ahold of a transcript of notes from an early screening, which includes a description of the voiceovers as "monotone and dry." Anyone who's watched the theatrical cut knows that's a pretty accurate description of Ford's delivery (though that's not a slight against the actor, just the writing). It's not surprising that in the aftermath, rumors circulated that the actor had intentionally tried to undermine the lines because of his disdain for them.

Ford didn't need to sabotage lines that were already bad

But Ford, who recorded the lines before he'd even seen a script, simply believed they'd never be used. According to an interview with Empire Magazine in 1999, even as he "contested [the voiceovers] mightily" and thought they were "not an organic part of the film," he was still bound contractually to do them. He told Playboy the unabridged version of his recording experience:

"Finally, I show up to do it for the last time and there's this old Hollywood writer sitting there, pipe sticking out of his mouth, pounding away at this portable typewriter in one of the studios. I had never seen this guy before, so I stuck my head in and said, 'Hi, I'm Harrison Ford.' He kind of waves me off. He came to hand me his pages. To this day, I still don't remember who he was, and so I said, 'Look, I've done this five times before. I'm not going to argue with you about anything. I've argued and I've never won, so I'm just going to read this 10 times, and you guys do with it what you will.' I did that. Did I deliberately do it badly? No. I delivered it to the best of my ability given that I had no input. I never thought they'd use it. But I didn't try and sandbag it. It was simply bad narration."

Ford's anecdote encompasses a lot of what he hated about the voiceovers: It's not just that he didn't think the lines were good or that they fit his character, but that as an actor, he was expected to contribute without giving his own input. That made him feel incredibly disconnected from the material, which obviously led audiences to feel the same way. "I had no chance to participate in it, so I simply read it," Ford told Empire. "I was very, very unhappy with their choices and with the quality of the material."

To this day, it's also still a mystery who it was that actually typed up the much-despised voiceovers. Evidently, Scott agreed with Ford because he removed them from his director's cut of "Blade Runner." But even that version of the film is marred in the actor's eyes. "They haven't put anything in, so it's still this exercise in design, which I think is spectacular, yet doesn't move me...at all," the actor told Empire again in its November 2000 issue. Though that's not the only reason Ford's view of the film soured over the decades.

Scott scrambled to add a happy ending

So this one actually is kind of Scott's fault. After the dismal reaction of those first two viewings of "Blade Runner," the director started to rethink the ending. Originally, and later in his approved director's cut, the film closed on a note of uncertainty as Deckard and Rachael (Sean Young) disappeared behind the closing elevator doors. But after audiences reacted poorly to test screenings, Scott was shaken enough to try and put together a last-minute scene that would give some closure regarding the fates of Deckard and Rachael.

"I wasn't keen on the idea," Ford revealed when Scott requested he and Young accompany him into the San Bernardino Mountains to film the new ending. But the director was able to win him over with the promise of good weather — after a dark, rain-drenched shoot, Ford was "delighted that we were shooting something during the day." Scott was even able to get Stanley Kubrick to lend him some unused helicopter footage from "The Shining." But that's about all the happy ending has going for it. And if Ford wasn't keen on the idea beforehand, he definitely didn't care for it after the fact.

Why the happy ending just doesn't fit

Ford had a similar issue with this hastily-shot happy ending as he did with the voiceovers: Mainly that it explicitly said or showed far more than what audiences needed to hear or see. The happy ending is probably the more egregious of the two since every aspect of it –- its tone, visuals, and even the inclusion of one final insipid voiceover –- feels drastically different from the entire film that precedes it. Ford might've been glad to have some sunlight, but nothing feels more incredibly out of place that those golden rays. Seeing Deckard and Rachael driving into a picturesque mountain forest almost feels suspiciously like a deus ex machina, with a lush woodland paradise seemingly manifested out of thin air and completely sweeping away the final impression of Scott's dreary urban sprawl. The message of the theatrical ending invalidates the dangers of a world still fixated on the violent dichotomy between humans and replicants, not to mention its environmental problems (hence the need for off-world colonies).

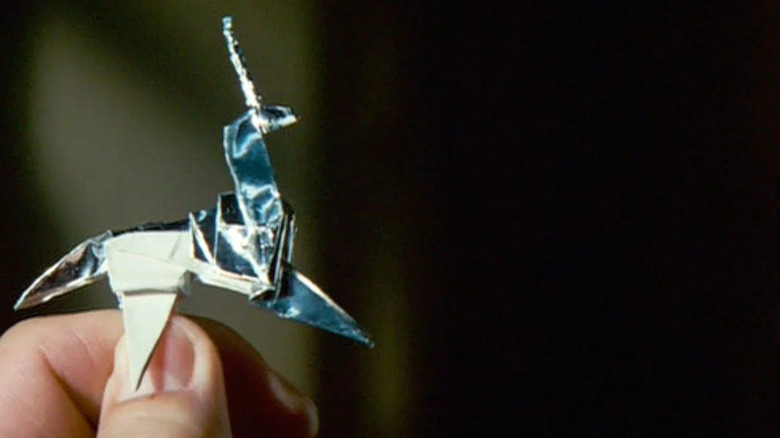

Of course, the main reason for the drastic switch in tone is that Scott decided to shoot the scene long after principal photography had wrapped, so he couldn't simply recreate the dystopia for that tacked-on scene. And crucially, the theatrical cut also lacked the revelatory unicorn dream sequence, a scene that casts a slightly optimistic light on Deckard's spotting of the unicorn origami figurine in the hallway. Without it, one can maybe understand why Scott felt the need to scramble to add something more conclusive. But a sunshine road trip that looks like the ending of a romantic comedy and not a dystopian sci-fi movie wasn't the way to go. All the director had to do was add the dream scene back in the film and stick to his adequately ambiguous ending — which, of course, is exactly what he did when he released his director's cut in 1992.