Every Planet Of The Apes Movie Ranked Worst To Best

Before "Star Wars," "Planet of the Apes" was the defining 20th Century Fox sci-fi franchise of the '70s — never mind that the series technically debuted in theaters in 1968, and is based on a 1963 French novel by "The Bridge over the River Kwai" author Pierre Boulle. The original five films spawned a franchise that includes a live-action TV series, a cartoon, comic books, and a line of toys — and remember, this was long before movie-based action figures were a regular presence in stores.

That was only the beginning. Even though the original "Planet of the Apes" films told a complete story with a beginning and an end, there was no way executives would let a series that successful die ... so, the studio tried to reboot it. Twice. One of those occasions resulted in a huge success; the other one, we barely talk about. Yet, in every evolution, the "Planet of the Apes" movies aspire to more than mere escapism. They all try to say something about how humans are — and aren't — like their primitive predecessors. More than almost any other franchise, these films tell different stories in each installment, and never seem afraid to end on a massive down note.

Although the property has come a long way, this is a case where newer isn't necessarily better. Here's how all of the movies in the "Planet of the Apes" series — the original films, the remake, and the prequel-reboot trilogy — stack up against one another, from worst to best. That's a tough task. For the most part, they're all pretty good. Well, all except one...

9. Planet of the Apes (2001)

Somewhere, someone is probably a fan of Tim Burton's "Planet of the Apes," but they probably don't admit it.

The sad thing is that so many things about this movie work individually, but don't when it's all put together. Going back to the original Pierre Boule novel, rather than the 1968 film, was smart. Rick Baker's makeup effects look outstanding; they're arguably the best practical prosthetics in the entire franchise. Tim Roth's physicality as a chimpanzee gives his villainous General Thade a wonderful "actorly" quality. Hell, even the notion of Mark Wahlberg acting opposite a real chimp sounds like a fun pitch in and of itself. At the time, Tim Burton also seemed like an inspired choice as a director, too, as he was guaranteed to bring a more surreal vibe to the proceedings.

What went wrong? Tim Burton's habit of ignoring the script in favor of the visuals, particularly when he makes adaptations, for one. As Mark Wahlberg told MTV, a rushed production schedule and pressure from the studio caused other problems. In addition, the film's big twist pales in comparison to the ones in the 1968 film and the novel — quite simply, it doesn't make much sense — and a wooden Estella Warren falls flat as Wahlberg's love interest.

Burton may have refused to do a sequel, but he got more out of the movie than most of us did. In casting Helena Bonham Carter, he began a professional (and personal) collaboration with the actress that lasted for 13 years, resulting in seven films.

8. Battle for the Planet of the Apes

Eschewing allegory for a more crowd-pleasing conflict where the good guys win — the first film in the series to do so — "Battle for the Planet of the Apes" is generally considered the least of the original five "Apes" movies. The fourth sequel plays a bit like "X-Men" in reverse. In trying to defeat evil mutants, the apes' loyalties torn between the integrationist chimpanzee Caesar (series regular Roddy McDowall) and the anti-human gorilla Aldo (Claude Akins). The humans who survived Earth's nuclear holocaust align with Caesar, whom we root for as their protector. It's basically a three-way battle, with just enough story to get viewers emotionally invested in the fight.

For once, the ending suggests that the cycle of violence that drives these movies may end in the future. However, this interpretation depends on one's understanding of the series' timeline. Is the story predestined to follow the path it already has, as "Escape from the Planet of the Apes" suggests? Or does the "Terminator 2" philosophy of "There's no fate but what we make" apply?

If the reboot trilogy represents the actual origin story for this franchise, that means that the timeline has already changed, but nobody could have possibly known that when this film was made. At least with humans still talking and living in harmony with apes years after Caesar's death, "Battle for the Planet of the Apes" ends on a rare note of potential optimism. Whether you choose to interpret the tear on Caesar's statue as one of joy or one of despair over what's to come is up to you.

7. War for the Planet of the Apes

Andy Serkis' modern version of Caesar becomes both Moses and Rambo in the final installment of the modern "Planet of the Apes" trilogy. With his forces caught up in a war against a rogue military unit that also includes traitor apes, Caesar seeks revenge on the Colonel (Woody Harrelson), a human who's responsible for the deaths of his wife and son. Cesar acts as a decoy while his tribe migrates to more favorable territory — a promised land, if you will. Meanwhile, even the humans who initially seemed immune to the virus that decimated society are struck mute by its latest strain.

Perhaps the subtext is meant as a tribute to Charlton Heston, who both famously played Moses and also helped make the original "Planet of the Apes" a smash hit. But the Book of Exodus reenacted by apes, complete with an act-of-God style avalanche that recalls the Red Sea drowning Pharaoh's soldiers, feels a little too on-the-nose. Perhaps this is the tale as the apes tell it, which would explain the scriptural and messianic tropes. However, without a narrative framing device like the one in "Battle for the Planet of the Apes," it all feels more like a collection of movie cliches than mythological archetypes.

Still, the pandemic paranoia angle plays better now than it did initially. It's also the most recent film in the series, and as such has the best special effects, which leads newer fans of the franchise to slightly overrate it — though, to be fair, they are extremely good effects.

6. Dawn of the Planet of the Apes

Essentially a slightly better remake of "Battle for the Planet of the Apes," "Dawn of the Planet of the Apes" replaces Aldo with Toby Kebbell's bonobo Koba, and the evil mutants with Gary OIdman and his army. Where this film most significantly one-ups its predecessor is in the intro, a lengthy, dialogue-free sequence featuring no humans whatsoever. It's a true depiction of a planet populated only by apes. Unfortunately, Jason Clarke's Malcolm eventually shows up to spoil the simian paradise as he tries to find a power plant deep in ape territory. Caesar and Koba, of course, differ significantly on how to deal with the incursion.

In "Rise of the Planet of the Apes," Andy Serkis found the just right voice for Caesar, especially given how few lines he had. Here, where Caesar has much more to say, he maintains an impressive seriousness. We never feel like the talking chimp is ludicrous. However, what makes this movie weaker than others in the series is that it doesn't really progress the narrative. It begins with the threat of war between apes and humans, and ends with the threat of war between apes and humans. In between, Caesar and Koba struggle over leadership, but there's never any real doubt about the outcome.

As for allegory, well, "Dawn of the Planet of the Apes" has a Martin Luther King-Malcolm X dynamic at work, as well as the notion that war is a failure of diplomacy. Nonetheless, very little about the dispute between the chimp and the bonobo feels as dangerous or provocative as the larger statements that the original films made.

5. Escape from the Planet of the Apes

Like many of the "King Kong" films, "Escape" becomes a massive downer the moment that you realize that the ape characters you're invested in have the odds stacked against them and will be brutally killed by the end of the movie. Then again, in the '70s, that was true of many non-ape movie protagonists as well.

In an impressive plot contrivance that gets around the destruction of the entire planet, "Escape from the Planet of the Apes" posits that sympathetic chimps Cornelius (Roddy McDowall) and Zira (Kim Hunter) somehow managed to rush home during the events of "Beneath the Planet of the Apes." Alongside their genius colleague Dr. Milo, they not only repair Taylor's spaceship, but fly it backwards in time. On present-day Earth, they initially become celebrities, but face a major backlash when they inadvertently reveal the planet's future.

Nowadays, "Escape from the Planet of the Apes" serves as a timely critique of the racist "great replacement" theory, with its depiction of U.S. government personnel who fear that the three (arguably "undocumented") aliens will ultimately breed children that will replace and conquer humanity. There's an element of classic Greek tragedy in there, too. In doing their damnedest to prevent a doomsday prophecy, the humans instead plant the seeds that will ultimately bring it about. It's a plea for tolerance and cooperation, and, like most of the "Apes" movies, a wistful acknowledgement that neither will be happening any time soon. "Escape" also boasts a great supporting cast full of well-known character actors, including Sal Mineo, Ricardo Montalban, Eric Braeden, and M. Emmet Walsh.

4. Beneath the Planet of the Apes

Charlton Heston famously refused to star in "Beneath the Planet of the Apes," and insisted that his character was killed off. As such, his screen time is minimal — he disappears at the beginning of the film, and reappears at the very end, only to die. That leaves James Franciscus to play a new astronaut, Brent, who spends most of the movie in search of Heston's Taylor. In that way, "Beneath the Planet of the Apes" is a forerunner of the modern "the main hero is missing" trend, which has popped up in films like "Star Wars: The Force Awakens" and TV shows like "Masters of the Universe: Revelation."

What keeps the first "Apes" sequel from being a strict retread of the original film is the addition of a new faction: the underground-dwelling, atomic bomb-worshipping mutant humans. With their hidden faces and veneration of global destruction, they probably played on the public's fear of communists at the time of the film's release; nowadays, they seem more like Christian nationalists. Their introduction results in one hell of an allegory during the climax, though, which tackles both the futility of war and the inherent destructiveness of religion. In addition, where the first film only hinted at nuclear annihilation, "Beneath the Planet of the Apes" concludes with the literal erasure of the planet Earth from existence. Alongside the first film's famous reveal, this ending sets the stage for a series of downer endings that's still unprecedented in a franchise as successful as this one.

"Beneath the Planet of the Apes" also proved that Hollywood remains eternally resourceful at continuing money-making series. Even the total destruction of the planet didn't prevent the studio from moving forward on a sequel before this one even hit theaters.

3. Conquest of the Planet of the Apes

The angriest and most blatantly allegorical "Apes" movie features obvious symbolism regarding slavery, and argues not merely for equality, but for subjugating the former masters and all of their allies and accomplices. It's so good at doing so that audiences, presumably made up entirely of human beings, feel like cheering when Caesar (Roddy McDowall) is moved to yell "Lousy human bastards!" In the future — one that, to Los Angeles residents, looks surprisingly like Century City — the apes are mostly mute, and have been trained to behave like human slaves. They've also evolved to look like people wearing ape makeup, a conceit we buy largely because three previous movies have already conditioned us to accept that look.

As originally filmed, Caesar, the son of the original film's Cornelius and Zira and the most intelligent ape on Earth in this far-flung future year of 1991, ends the movie with a speech declaring that humans' only purpose from now on will be to serve apes. This horrified test-screening audiences, so Fox used clever editing and newly recorded lines to make Caesar decry vengeance instead, changing his speech to focus more on equality. Basically, Caesar became Professor X rather than Magneto. (The original version of the movie was released decades later on Blu-ray.)

This sentiment carried over to the fifth and final installment of the original series of "Apes" films, although the reboot series' new Caesar has fewer qualms about killing humans. Then again, in an age where people sport "Thanos was right" merchandise, that kind of rhetoric isn't as big of a commercial risk as it once was.

2. Rise of the Planet of the Apes

It took 10 years for the "Planet of the Apes" franchise to recover from Tim Burton's film, but when it did, the result pleased most fans and critics. A kinda-sorta remake of "Conquest of the Planet of the Apes," "Rise of the Planet of the Apes" constructs a new origin story for Caesar, who, thanks to sophisticated motion-capture technology, can still be played by a human, but now looks like a realistic chimpanzee. Andy Serkis, who previously wowed audiences with a similarly hybrid performance as Gollum in the "Lord of the Rings," was the natural choice to bring this new Caesar to life.

"Rise of the Planet of the Apes" leans more on the topics of animal and elder abuse than racism, with an experimental Alzheimer's drug turning out to be the cause of both intelligent apes and a human-decimating pandemic. John Lithgow's a heartbreaker as the senile father to James Franco's well-meaning chemist Will Rodman; for once in a "Planet of the Apes" film, the humans and apes merit equal sympathy. We root for Rodman to find his miracle cure, even as we suspect that he's doomed to fail, while also cheering on Caesar's escape from Tom Felton and Brian Cox's awful father-and-son animal abusers. Meanwhile, a quick reference to a spaceship launch that closely resembles Taylor's in 1968's "Planet of the Apes" positions "Rise" as a sort-of prequel.

When Caesar finally speaks, the moment is as powerful as when Taylor does the same in the 1968 film. Since Caesar is a realistic CG ape, seeing him utter English words could have ruined the movie (and the budding reboot franchise) with its silliness. In the metaphorical hands and literal vocal chords of Serkis, however, the moment hits the perfect note.

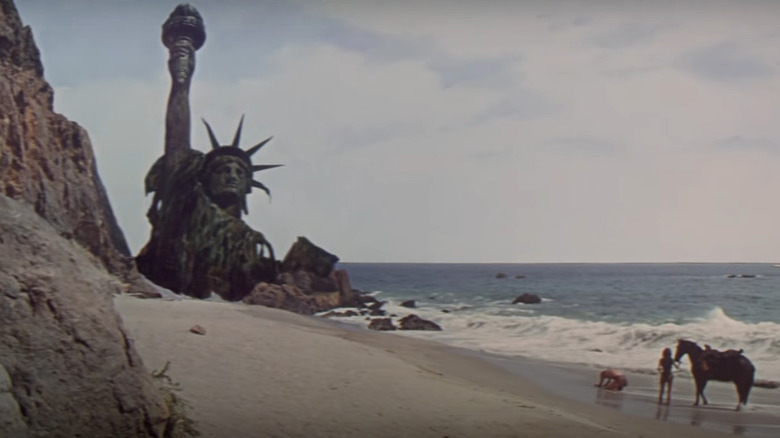

1. Planet of the Apes (1968)

It's hard to beat the original. No successor could possibly break the same ground in the same way. Even if another sequel could somehow pull off a twist of the same magnitude, it'd have a tough road to the top spot, because even putting the reveals and allegories aside, "Planet of the Apes" is a damn good movie. Charlton Heston's best-known role may be that of Moses in "The Ten Commandments," but his trio of cautionary sci-fi classics — "The Omega Man," "Soylent Green," and "Planet of the Apes" — have arguably stood the test of time much better. Like William Shatner in "Star Trek," Heston understood that a combination of slightly heightened acting and complete commitment to the absurd material would elevate both his performance and the story. Just like Moses, he's best on screen as the lone truth-teller in a society gone mad (in films, anyway; in real life, not so much).

If "Planet of the Apes" were made today, fans of the novel would probably cry foul over all the changes. Those changes, however, helped make the film iconic. The final twist, which was conceived by "The Twilight Zone" creator Rod Serling and reveals that the "planet of the apes" is actually a post-nuclear Earth, has been imitated many times, but still packs a punch. It's an earlier moment, though, that really maintains its power to electrify: After being rendered temporarily mute, Heston's Taylor finally regains his voice and yells, "Get your stinking paws off me, you damn dirty ape!" The sheer dramatic catharsis of that moment is a perfect payoff to all the trials that have led up to it.