Star Trek: The Motion Picture Ending Explained: Something Bigger Than The Cosmos

The late author Douglas Adams succinctly wrote in his 1979 novel "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy," that, "Space is big. You just won't believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it's a long way down the road to the chemist's, but that's just peanuts to space." Adams wrote science fiction stories with the vastness of time and the cosmos in mind, albeit for a comedic effect. In one of his novels, characters could travel forward in time to the very end of the universe and find that a restaurant had opened near the point of universal collapse so that the wealthy could witness it as part of an evening's light dinner entertainment (repeat visits were possible through a complicated temporal something-or-other). For Adams, the infinity of time and space was fodder for humor, as he would insert the mundane into any potential moments of awe.

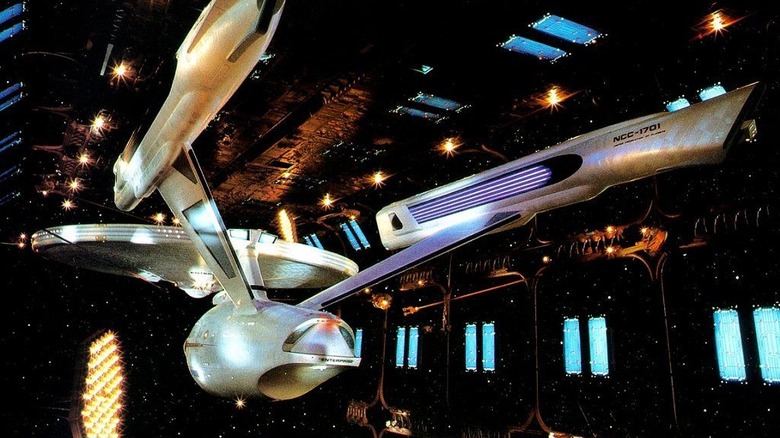

The same year "Hitchhiker's Guide" was published, Paramount produced "Star Trek: The Motion Picture," the first feature film to be based on the low-budget sci-fi series that hadn't seen TV screens since 1974, and hadn't been seen in live-action since 1969. Taking aesthetic cues from Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey," "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" was "Star Trek" writ large. No longer constrained by rinky-dink television budgets, the feature film was now permitted to depict the show as massively as it always felt. For instance, the U.S.S. Enterprise was luxuriated over in a four-and-a-half-minute sequence that many people now find risibly indulgent.

But the length and scope was the point. "Star Trek," in the best of cases, brushed up against some of philosophy's larger questions. "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" had ambitions no smaller than to unlock the meaning of life and humankind's place in the heavens.

Voyager VI: The Undiscovered Country

They briefly recount the film's story: It has been years since the Enterprise crew was assembled. A mysterious space cloud, hundreds of light years across, is slowly drifting toward Earth and swallowing up any starships or space stations it happens to run across. It has no definite shape and is not communicating. Admiral Kirk (William Shatner) is re-assigned to the starship Enterprise, currently commanded by Capt. Decker (Stephen Collins), and ordered to take it out to the cloud to investigate. The entire cast of the original show joins in, as does a bald, stoic Deltan named Ilia (Persis Khambatta). The Enterprise is able to penetrate the cloud and sail inside. They find chamber upon chamber of what might be machines, but it is difficult to comprehend. Whatever the cloud is, it's far beyond human understanding. A lot — a lot — of "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" is devoted to scenes of the Enterprise floating through the cloud.

In order to communicate with the humans on the Enterprise, the cloud abducts Ilia and replaces her with a robot-like clone that speaks as its emissary. The robot clone explains that the cloud is called V'Ger and that it aims to return to its maker. Students of science fiction will perhaps recognize that V'Ger was once of Earth origin.

To skip ahead a bit V'Ger was the bowdlerized name of the Voyager 6, a fictional NASA probe launched from Earth a century before. It was initially just a machine, sent out into the cosmos to retrieve information and return it. Something unexplained happened to the Voyager 6 in the ensuing century, and it grew to contain all knowledge in the galaxy, growing to enormous size in the process. It was now fulfilling its mission to return its findings.

The sexual politics of The Motion Picture

It's worth noting that a lot of "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" has been devoted to a certain degree of romantic and sexual tension between Ilia and Capt. Decker. Ilia is a Deltan, which causes a few of her crewmates to raise their eyebrows. Ilia makes mention of her vow of chastity, a curious thing to announce on the bridge. According to the novelization of the film written by Gene Roddenberry, Deltans are known to be highly sexual and have intercourse quite freely. In order to curtail fraternization, Deltans take their vow before entering the Academy. Although Ilia was replaced by a robot clone, Dr. McCoy (DeForest Kelley) notes that Ilia's brainwaves were replicated as well, leaving her lust and her love for Decker intact.

The robot — and by extension V'Ger — seems to be experiencing love for the first time. Also lust. V'Ger is, after a century, finally going through a form of cosmic puberty. Sex is most certainly one of the film's central themes.

At the conclusion of "Star Trek: The Motion Picture," Kirk and company have found the original V'Ger probe at the heart of the cloud, deciphering its name and discovering its purpose. V'Ger, having felt love, wants to know more, as love and lust, it seems, are the final components of the universe that V'Ger needs to make sense of everything. Decker, declaring his love for Ilia, steps onto a platform, and V'Ger begins to physically absorb him. It's a beautiful, almost spiritual experience. Ilia, feeling the love as well, steps onto the platform with him, and the pair ascend. In a flash, the entire massive V'Ger cloud explodes into the universe. It now knows everything.

Childhood's end

After the cancelation of "Star Trek," the show was put into eternal syndication, and it was only then that it found its massive audience in reruns. "Star Trek" gatherings, then conventions, became common, and Gene Roddenberry, as well as the cast, would attend to kibitz. It seems that during this period, Roddenberry finally came to realize the more expansive themes of "Star Trek." Audiences reacted to the show's multiculturalism and optimism about the future. The Prime Directive assured us that "Star Trek" was an anti-colonialist show, and the technology depicted was our friend. The Enterprise was not a battleship, but an exploration vessel. The show, Roddenberry figured after the fact, was meant to be utopian.

As such, when it came time to make "Star Trek: The Motion Picture," it stood to reason that it would reach far. Roddenberry, ever the free-love hippie, wanted to tell a story where all facets of the universe could come together, scraping the outer edges of the cosmos, and then extending beyond. V'Ger had been traveling for an unspecified time (a time-warp is implied) and knew all the facts it could know. What it lacked, naturally, was heart. Human beings, and their capacity for love, was the missing element of the universe. Our existence, Roddenberry argued, was a vital element holding everything together.

V'Ger finally learned to love and experienced the glories of sex. Its explosion was, essentially, a galactic orgasm, as if V'Ger was going through puberty. It was the end of its childhood and a passage to a higher plane. V'Ger is, of course, a symbol of humanity as it is seen in "Star Trek." Like in "2001: A Space Odyssey," the cosmos is our next step of growth. We pass into the stars, and we are no longer children.