Studio Ghibli Movies Have Much More To Offer Than A Vibey Anime Aesthetic

I saw "Spirited Away" for the first time as a child via a rental DVD in a New Hampshire farmhouse buried in snow. I was so taken aback that I had to see it again immediately. This time I demanded that my parents join me. Early in the film, when the heroine Chihiro is threatened by a mysterious frog man, her friend Haku traps him in a magic bubble. "It's a Pokemon!" my mother cried. "He's in a Pokeball!" The visuals of "Spirited Away" had so discombobulated my family that they could only grasp at reference points. Critics were similarly taken aback when the film came to the United States in 2002. Nigel Andrews wrote in the Financial Times that "Spirited Away" is a film that "sums up all existence and gives us a mythology good for every society, amoebal, animal or human, that ever lived."

In the years since it's become easy to take Studio Ghibli for granted. Stores sell No Face pencils and Totoro dolls. Director Hayao Miyazaki's heroines have been dissected, redrawn, and choreographed to "lo-fi beats to study to" via every social media platform that exists. Few other anime studios have produced work as beloved or influential. Even so, I can't help but wonder if that mass familiarity obscures the core of their films. What does Ghibli look like behind Hayao Miyazaki's smiling face? Strip away the layers of nostalgia, defamiliarize the studio's films, and a new picture emerges. Not a return to youth, but a glimpse of something older and wilder.

The power of Studio Ghibli

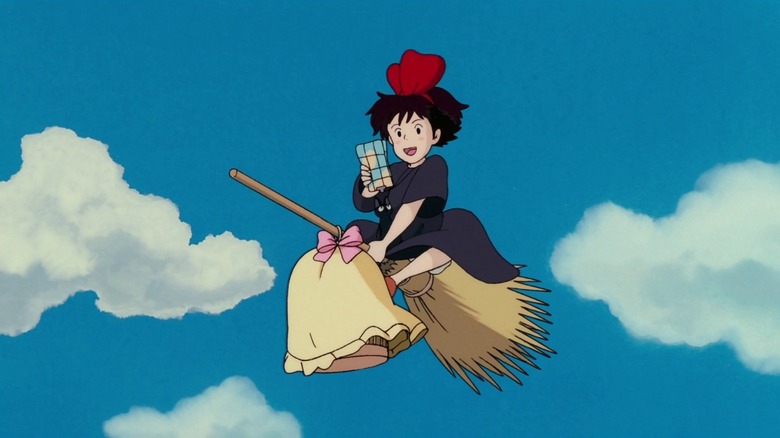

The films of Studio Ghibli became popular precisely because they were able to reach a general audience beyond anime fandom itself. Of course, this was not always the case. "Ghibli films only broke even or made a modest profit through most of the 1980s," says Jonathan Clements in the book "Anime: A History." While "My Neighbor Totoro" is now a merchandising giant and "Grave of the Fireflies" a touchstone of tragic cinema, it was not until "Kiki's Delivery Service" in 1989 that Ghibli started really making money. Even so, each film laid the foundation for later successes. Those who watched early Ghibli films as kids took their children to see "Princess Mononoke" and "Spirited Away" in the following years. "When a Ghibli film is truly popular," says Clements, "it can lure in entire family groups, vastly increasing its likely revenue ... "

Moving people's hearts with the power of animation has always been Studio Ghibli's ethos. Helen McCarthy quotes Hayao Miyazaki in "Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation" as saying, "the honest expression of simple, powerful emotions can strike people's hearts in animation as strongly as in any other medium." Also critical to Ghibli's popularity was the producer Toshio Suzuki. Director Mamoru Oshii would claim in his essay "The Animation of Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata and Studio Ghibli" that it was Suzuki who pushed Miyazaki to make "Kiki's Delivery Service," "based on his [...] own instinct as a great producer." Miyazaki's heroines were traditionally pure-hearted, innocent maidens; it was Suzuki who thought audiences would find them more relatable if they went to the bathroom sometimes.

Miyazaki the tank

Of Studio Ghibli's two great directors, Hayao Miyazaki is seemingly the most knowable. His films are loaded with repeating motifs: technology versus nature, flying machines, and independent young heroines are just a few of them. Miyazaki is also the most prolific director at Studio Ghibli, having directed nine films at the studio (plus "Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind," a Topcraft film that has since been brought under the Ghibli branding umbrella.) Watch enough of these films, and it's easy to believe that you have the man pinned down. In 2014, the webcomic "Zen Pencils" released a trilogy of comic strips where a caricature of Hayao Miyazaki commands a giant robot to defeat the world's "trolls" with the power of creativity. The artist sincerely believed that their vision of Miyazaki as a pure, benevolent genius reflected reality. In fact, they were deeply mistaken.

The real Hayao Miyazaki is a force of nature. Susan Napier quotes Miyazaki's mentor Yasuo Otsuka in her book "Miyazakiworld," saying that Miyazaki was always "rolling forward like a heavy tank." Mamoru Oshii would say in an interview that "Miya-san is a bit like a Trotskyist," and compare Studio Ghibli to the Kremlin in the same breath. Miyazaki himself could be absolutely scathing in his critique of the anime industry. "Japanese animation started when we gave up moving," he said in his essay "About Japanese Animation." His films are a never-ending battle against "excessive expressionism" and the "voraciousness" of the TV anime industry, which he saw as antithetical to the animation process. Miyazaki wanted to do more than just make children smile. He wanted to make anime that they could believe in.

Takahata the sloth

Even more dangerous than Hayao Miyazaki is Isao Takahata, who Miyazaki affectionately named "Paku-san" (Sloth). Takahata made just five films after the formation of Studio Ghibli, but they are considered by critics to be among the best the studio ever produced. His television series "Heidi, Girl of the Alps" and "Anne of Green Gables" are also two of the most beloved anime of the 1970s. Frankly, they look better than most television anime made today. Takahata's final film, "The Tale of Princess Kaguya," took eight years to make and looks unlike any film released under the Ghibli banner. While Miyazaki's films pioneered the Ghibli aesthetic, Takahata's rare films revealed the enormous, almost unsustainable ambition bubbling under Ghibli like a supervolcano.

As part of Anime News Network's "Endless Memories" retrospective on Takahata's body of work, Mike Toole says of Takahata that "it wasn't just enough [for him] to make characters who looked cool doing interesting stuff; he had to put them in settings that felt every bit as complete and detailed ... " At times this meant doing extensive location photography during pre-production, as he did during the making of "Heidi." At other times, it meant building out every detail of a scene, regardless of its importance. Manga editor Carl Horn told a story for "Endless Memories" in which Takahata requested Hideaki Anno draw the famous Maya heavy cruiser of World War II for "Grave of the Fireflies." Anno spent a month on the task, only for Takahata to "shroud the motion of the ship in shadows, where ignorant armies clash by night." The ship was just another object to Takahata, but it had to be built. The greatest strength of animation, after all, is the ability to control every aspect of reality.

The crucible of Horus

The first film Isao Takahata ever directed was "The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun." Takahata made the film at Toei with a team of talented animators including Hayao Miyazaki, his mentor Yasuo Otsuka, and many others. Takahata's union involvement meant that the film was, as Claire Napier says in "Miyazakiworld," the "first movie ever made in Japan by a team of supposed equals." Takahata, Miyazaki, and company put all of their hopes, dreams, and fears into the movie, channeling the activism of 1960s Japan. The resulting production went so over time and budget that Toei demanded the film be released before it was ready. Two setpieces in the film remain unfinished to this day. "The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun" was a commercial flop that briefly made Takahata an outcast in the commercial anime world. But it is also arguably the first great Japanese anime film.

"The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun" bears all the marks of what would become the Studio Ghibli ethos. The film indulges in fantasy but takes place in an obsessively detailed world. The characters interact with that world as if they live in it, rather than simply passing through it as they still do even in contemporary anime productions. Takahata and his crew capture the feeling of myth even as they carefully depict the cast's daily rituals and customs. The Norse setting of "Horus" was imposed upon the film by Toei, who believed the film's original Ainu setting would be too controversial. Even so, the film feels oddly specific considering its difficult origins.

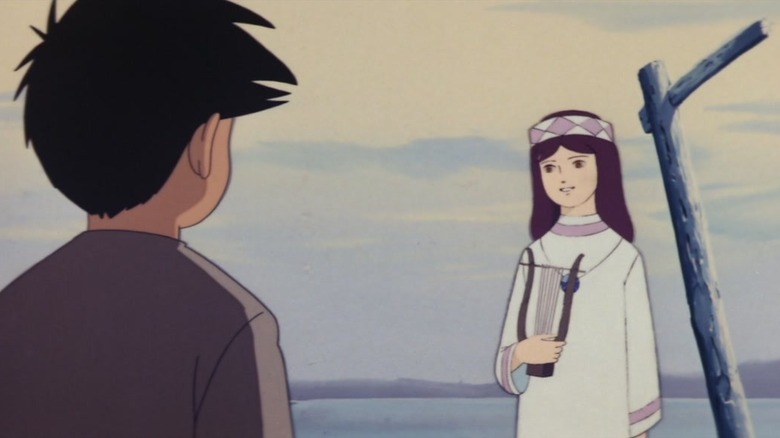

Hilda's world

"The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun" is partially about Horus, a boy who must defeat the villainous Grunwald. But it is also about Hilda, a young woman who rapidly steals the movie as soon as she is introduced. Hilda is a loner with a beautiful singing voice. But we soon learn that Hilda is Grunwald's sister, and is torn between empathy for others and the cruelty imposed on her by loneliness. Thanks to the skills of Yasuji Mori, who created the character and animated many of her scenes, Hilda takes on remarkable depth. She is the prototypical Ghibli heroine and villain at once, an independent woman who does terrible things but is never irredeemable. Anipages writer Ben Ettinger would call Hilda "the single most psychologically penetrating animation of a character to grace any Japanese animation up until that point."

It was not until I saw "Horus" that I felt as if I understood Studio Ghibli. They are more than just a vehicle for appealing fantasies, although they are certainly very good at that. They are a world-creation engine. The staff of Ghibli believed that through hard work, dedication, and craftsmanship, they could create a reality with the power of animation. If this frightens you, you're not alone. The creation of worlds is a lot of responsibility, and may even be unsustainable. There's a reason Isao Takahata only made a handful of films, and why many talented craftspeople have left the studio. Even so, thinking about what his team accomplished fills me with awe. Nigel Andrews may have been closer to the truth than I thought. Studio Ghibli may not "sum up all of existence" in totality, but the dreams of its founders certainly do.