The Unpopular Opinion: 'The Matrix Reloaded' Is The Great Misunderstood Sequel Of The 2000s

(Welcome to The Unpopular Opinion, a series where a writer goes to the defense of a much-maligned film or sets their sights on a movie seemingly beloved by all. In this edition: we go to bat for The Matrix Reloaded on its 15th anniversary.)

If the burden of a sequel is to equal or better its predecessor, then few movie sequels have inherited as great a burden as The Matrix Reloaded did when it first hit theaters 15 years ago today on May 15, 2003.

The first Matrix movie gripped the public imagination, tapping into something deep in the collective unconscious. Steeped in grandeur, a sense of pre-millennial purpose, it was a motion picture that wielded the same kind of myth-making mojo as the original Star Wars trilogy. If anything, back in 1999, The Matrix was more Star Wars than Star Wars, as evinced by how widely it overshadowed The Phantom Menace that year as a cultural phenomenon.

The Matrix Reloaded's legacy as a sequel is such that it and The Matrix Revolutions often get lumped together as inferior specimens. In terms of simple storytelling effectiveness — the lucidity of their dream-weaving as movie machines — both films are inferior to the smooth-running high-concept engine that was the first Matrix. But while the law of diminishing returns is at play in The Matrix trilogy and Reloaded does show signs of the impending system failure that Revolutions would bring about, it actually manages, despite its infamous cave rave scene, to expand the series mythology in new and interesting ways. A decade and a half later, the film's dismantling of the oosen One narrative set up in The Matrix gives it a different but no less intriguing pull, one that takes to the freeway and attempts to broaden the viewer's perspective on reality in a manner that now seems ahead of its time.

Action and World-Building

Like its predecessor, The Matrix Reloaded is a movie that stimulates the senses with action while engaging the viewer's intellect with a set of profound questions. The action is sort of the shallow end of the pool in terms of what the movie has to offer, but it's part of what makes the movie entertaining and enables it to play with other weighty ideas, so let's talk about it first.

This is a visually inventive sequel that mostly succeeds on the world-building front as it introduces new elements like rogue programs, ghosting albino twins, and a hallway full of backdoors in the system (all of which lead to cool fight scenes). Having Hugo Weaving's Agent Smith become a computer virus who can replicate himself onto others, converting them into clones of himself, gives us one especially memorable confrontation between him and our returning hero, Neo, played by Keanu Reeves.

The CGI in the "burly brawl" — in which a small army of Smiths takes on Neo — does stick out and make the scene look like a video game in some of its wide shots. But for what it's worth, I happened to rewatch The Matrix Reloaded the same day Black Panther hit iTunes, and comparing the two films (both of which I love), I honestly felt like the only thing that made the CGI in the burly brawl any worse was the fact that it was being used to recreate the human face in broad daylight, whereas Black Panther has a mask and he's somersaulting over cars at night. Yet The Matrix Reloaded is a movie that's 15 years older, so if anything, it deserves to be extended more grace for the quality of its visual effects.

Even if the effects in some of Reloaded's shots aren't of unimpeachable quality, the burly brawl is just the film's first big action set piece. There are other moments in Reloaded that hit action-movie arias and remain utterly thrilling to watch even to this day. One is the chateau fight, where Neo takes on a gang of henchmen in a chateau whose walls are lined with seemingly every medieval weapon imaginable. This scene is bolstered by skillful choreography, urgent music, and pure cinema style, yet it's a mere prelude to the freeway sequence, which hits the road in a silver Cadillac CTS and shows us something bigger and better, more ambitious than anything we saw in the first Matrix movie. The way they build up the freeway like it's going to be a suicide run only escalates the tension that much more when Laurence Fishburne's Morpheus faces off with a nearly invincible Agent on top of a semi-truck.

He's protecting an exiled locksmith program called the Keymaker. It follows naturally from the idea of sentient A.I., but having some programs that face deletion choose to hide in the system rather than return to the machine mainframe is a neat flourish that we never got to see in the first film. Details like these open up a new frontier inside the dream world of the Matrix, teasing the imagination with its limitless potential.

A Franchise at a Crossroads

No wonder they're looking to revive the Matrix universe on-screen with future possible movies. The short-film anthology The Animatrix, released on DVD a few weeks after The Matrix Reloaded, showed that there were other corners to this world that could be fleshed out enough to sustain their own mini-narratives. Why not another feature film?

That was the thinking, anyway. For most of 2003, it seemed like The Matrix franchise held endless prospects, but as it turned out, the franchise was at a turning point where there wasn't enough being held back for the next sequel and it was about to lose its way. It's easy to forget this now, but the more precipitous drop-off in quality in the trilogy actually occurs between The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions.

The fact that these two movies were filmed back-to-back and released within six months of each other has led to a kind of guilt by association. The last time I sat down and tried to rewatch Revolutions, I felt myself checking out mentally as it degenerated into a storm of ugly, mechanical visuals. Squid-like Sentinels besiege a blue-filtered underground city defended by lurching exoskeletons, which look like the power-loaders from Aliens armed with machine guns. And it's as if the once-great Matrix franchise has come full circle to where it is now, as mind-numbing as the Star Wars prequels.

Where the franchise falters in its world-building is in its introduction of new characters. This starts with Reloaded, where a number of fresh faces pop up as the series attempts to build out its supporting cast. To its credit, it does this in a refreshingly diverse manner for an early 2000s film, but alas, not all of those faces really register or leave much of an impression. Those that do are the ones that belong to actors with natural charisma like Jada Pinkett Smith, who was already known. Likewise, Harold Perrineau, on the cusp of playing Michael on Lost, does bring an affable charm and some welcome comic relief to his character.

Aside from them, however, even Neo is annoyed by new characters like the worshipful Kid (that's his name, apparently), who recalls that other skinny goof, Mouse, jabbering about "Tastee Wheat" in the first movie. The first Matrix killed off most of its supporting characters; its sequels compensate for this by amplifying the Lando Calrissian effect, as it were. If you aren't aware of his backstory from The Animatrix, then the sudden appearance of Kid and focus on his face in-camera might just seem random and inexplicable, rather like the diversions with Jimmy in Peter Jackson's King Kong.

For the most part, however, newbies like Kid are relegated to the sidelines until Revolutions, when they take center stage at times and the characters we know and love, those we really care about from the first movie like Neo, Trinity, and Morpheus, start to fade into the background a bit. If the trilogy had stuck the landing with Revolutions, we might all be inclined to regard Reloaded more favorably. Part of what makes the first sequel work better than the second is because — in straightforward cinematic terms, divorced of any philosophical, blue-versus-red-pill symbolism — the world of the Matrix, with its infinite possibilities, is inherently more interesting than Zion, where the residents all look like they're wearing clothes from a Mad Max garage sale.

The funny thing is, those tattered fatigues ("sweaters of the apocalypse") may have helped inspire a clothing line from Kanye West. West has compared The Matrix to the Bible and whether or not it was intentional, some of his Yeezy apparel does look like a Matrix homage.

In Defense of Dance Parties

Speaking of Zion, despite the unforgettable freeway sequence, one of the first things that comes to mind for a lot of people with The Matrix Reloaded may, unfortunately, be the cave rave. So let's address that next before we get into the meat of what makes the movie work. Director Jordan Vogt-Roberts (Kong: Skull Island) is right: the cave rave is a scene that "deserves a universally agreed upon moniker a la 'nuke the fridge' to address its cringe." I like that "cave rave" rhymes, so I'm going to go with that moniker here.

Whatever you want to call it, it's a scene that lives in infamy among film buffs. The inhabitants of Zion, the last bastion of human civilization on Earth, have gathered in a huge cavern full of impressive stalactites, where Morpheus (always the trilogy's best character) is delivering a stentorian speech. It comes off at first like one of those meant-to-be rousing war speeches, the kind where you can feel the screenwriters chasing Braveheart. With his bellowing voice, Morpheus talks about the 100-year war between humanity and the machines and how those machines are bearing down on Zion even as he speaks. He then declares:

"Tonight, let us shake this cave! Tonight, let us tremble these halls of earth, steel, and stone! Let us be heard from red core to black sky! Tonight, let us make them remember: this is Zion, and we are not afraid!"

It's a tremendous build-up that dissolves into...a dance party. Morpheus himself doesn't dance (though his old flame Niobe does slyly say, "I remember you used to dance. I remember you were ... pretty good.") Instead, we see a lot of extras who look like underwear models dancing. There are bared torsos, ankle bracelets, wet dreadlocks, and seen-through-nylon nipples. People gyrate in slow-motion. Others jump for joy as if to say, "Yes! I am alive outside the Matrix!" All of this is intercut with a bout of lovemaking between Trinity and Neo. They, too, are alive, though Neo sees ominous flashes of Trinity falling to her death in a dream he's had.

That, we can surmise, is really the whole point of the scene. While it may be weirdly executed, it's meant to be a final celebration of life unplugged. All things considered, the cave rave isn't as bad as you might remember it. In 2018, it's a scene that reminds me very much of an episode of AMC's superb The Terror, in which a bunch of sailors marooned on the ice decide to throw a slightly ridiculous Venetian Carnival in the middle of the Arctic. I think it's actually somewhat realistic that on the eve of their own destruction, in the face of certain death, you would see people trying to justify their existence any way they knew how.

If you meet the cave rave on those own terms, then the dancing of Zion's freedom fighters could even be considered tame. Less enlightened end-of-the-world revelers would probably surrender themselves to oblivion by indulging in much worse hedonism than a little dancing. People refer to the scene sometimes as an "orgy," but dancing is a far cry from Caligula.

It does show, however, that humankind's survivors are still capable of enjoying sensual pleasure outside the Matrix. If the first Matrix movie functions on one level as a metaphor for the spirit and the flesh, then the cave rave in all its awkwardness is perhaps the first major signpost that the Matrix sequels will be messing with conventional dichotomies like that. In the end, even if you find the scene indefensible, it's certainly no worse than the "Jedi Rocks" musical number in Return of the Jedi. Plenty of fans can overlook that scene and still enjoy the rest of Return of the Jedi because it has so much else working in its favor. So it goes with The Matrix Reloaded.

You Were Supposed to be the Chosen One!

Aside from occasionally spotty CGI and hit-or-miss new supporting characters — which are, in and of themselves, forgivable flaws, not deal-breakers — The Matrix Reloaded may partly be misunderstood because it deliberately subverts the audience's foundation of understanding from the first movie. When it comes to The Matrix, the Star Wars comparison is apt not just because of the movie's mythic splendor and cultural significance, but because of how it drafts the initial arc for its main character using the same basic template that George Lucas would employ: first with Luke Skywalker, then (in a more overt, less successful fashion) with his father Anakin in the prequel Star Wars trilogy.

In 2015, an Entertainment Weekly article critical of their work talked about how the Wachowskis, the writing and directing duo behind The Matrix, essentially became Lucas in their later career, with the "pointless peacocking decadence" of Jupiter Ascending echoing the hollow green screen spectacle of The Phantom Menace. The Matrix, by contrast, struck a much more populist nerve. The movie's legacy is solid; it is what it is and there's no taking away from that. But beyond obvious factors like its trendsetting action — the slowed-down "bullet time," the balletic wire work it brought to the mainstream from earlier kung fu movies — maybe part of its success can be attributed to how neatly and effectively it repackaged the monomyth or hero's journey that we've seen a million times over in film and literature.

When we first meet Thomas Anderson, AKA Neo, he's "living two lives," one as a software programmer, the other as a hacker. The programming job sees him dwelling in a cubicle on a drab office floor, where he's under the power of a boss who likes to lecture him about being late. From these humble beginnings, he will eventually go on to realize his destiny as "The One," a figure prophesied to save humanity from a mechanized controlling force.

It's not so different from the arc of Luke, the farm boy of secret parentage who goes on to become a universe-saving pilot and all-powerful Jedi in the fight against the machine-driven Empire. Lucas would frame Anakin in outright messianic terms as "The Chosen One;" and in The Matrix, one character spells it out for us in a similar fashion at the beginning when he tells Neo, "You're my savior, man. My own personal Jesus Christ."

If you go back and watch The Matrix , it's obvious now that it has such a blatant Hollywood ending. Right at the point when it looks like all hope is lost, Trinity confesses her love to Neo. Neo's heart starts beating again and he rises triumphantly from the dead, capable of stopping bullets, fending off blows one-handed, and seeing the green lines of code in the Matrix. The movie has already given us those hammy little finger-waves and fighting poses, not to mention some cheesy lines of dialogue ("Listen to me, coppertop, we don't have time for 20 questions." Or my personal favorite: "Neo, this is loco!") But the feel-good ending really seals it that this movie is meant to be a winking crowd-pleaser.

Behold the One! Look at how self-assured Neo is as he twists and displays his outstretched kicking foot after using it on the nefarious Agent Smith. It's a fist-pumping moment in a movie where the central metaphor is clear, laid out for us in dualistic, almost Manichean terms by the red-pill-versus-blue-pill choice. Reality is not real, and there exists something truer beyond this veil of illusion called life. Humans being used as living batteries by the Matrix can either awaken to that truth or remain blissfully ignorant cogs in the machine.

Neo is the One. He's Jesus. We never see him walk on water, but he does fly off like Superman at the end. Is it any surprise, then, that The Matrix holds quasi-religious significance for some people? Only recently has the meaning of the pills morphed into a kind of uber-political, red-state-versus-blue-state symbolism, with the aforementioned Kanye West's pro-Trump and alt-right-leaning tweets being referred to as a "red pilling" on sites like Vanity Fair and Wired. As the latter notes, "The ideas and the imagery of The Matrix run through internet culture like an aquifer." (All of this is especially ironic as the Wachowskies are transgender, meaning that these conservative groups have borrowed the language of two trans artists whose work could very easily be read as being about their transition.)

It just goes to show the film's enduring appeal. The Matrix is a movie that, among other things, provides a vivid conceptualization of a powerful life metaphor, and when its sequel broke down that metaphor and muddied the mythology with more complex ideas, it would leave many viewers scratching their heads and feeling dissatisfied.

It's the Question That Drives Us

If the first Matrix offers up a palatable, self-contained "Chosen One" narrative, one that paints in mythic broad strokes, then what The Matrix Reloaded does is deconstruct the myth. Traditionally quite press-shy, the Wachowskis have nonetheless gone on record to say that this middle stage or second act of deconstructionism was part of their philosophical intentions with The Matrix trilogy.

As it calls into question things from the first movie, revealing that the trusted, motherly Oracle is an A.I. and that the hope-inspiring Prophecy of the One is another "system of control" (like the Matrix itself), the sequel places us on unsteady footing. It presents a more challenging, less safe and secure narrative for the new millennium, yet in many ways, that narrative now seems achingly prescient and ahead of the curve for a 2003 film.

Within the science fiction genre, a good recent point of comparison would be the arc of Ryan Gosling's character in Blade Runner 2049 — how he comes to realize that he is not as special as he thought he was. Stuck in a hope loop, cycling through history: that's the kind of post-Y2K hangover that a lot of people who came of age around the turn of the millennium have probably shared in the early 21st century. If you want to go Star Wars again, you could even compare it to how The Last Jedi reveals that Rey's parents were nobodies and that the future of the universe may lie not with Skywalkers, but with other nobodies like Broom Boy.

It's difficult to accept, but in a sense, we as viewers of The Matrix and The Matrix Reloaded are forced to undergo the same poignant arc as Morpheus, the true believer who invests unfailing faith in Neo, tossing out sentiments like, "I do not see coincidence. I see providence. I see purpose." And later: "I do not believe it to be a matter of hope. It is simply a matter of time."

At the end of Reloaded, this same character is left quoting the Book of Daniel, saying, "I dreamed a dream ... but now that dream is gone from me." It turns out that Morpheus, as wise and all-knowing as he seemed, had himself been caught up in a blue pill effect with the Prophecy of the One. The end of the movie leaves him completely unmoored from what he knew. We all felt that, maybe, in theaters back in 2003, as our brains were left reeling from the scene with the Architect, where it was revealed that the One was a systemic anomaly that arose out of free will and was allowed to play itself out cyclically to avert "the escalating probability of disaster" within the Matrix.

Parodied memorably by Will Ferrell in an MTV Movie Awards sketch ("Ergo! Vis a vis! Concordantly!"), the Architect's exposition of the One's true purpose is at first confounding, then compelling once the full implications of it sink in and you realize that Neo may actually be living something akin to the nightmare loop of Roland Deschain at the end of The Dark Tower novels. It's not altogether clear at first: the Architect's verbose manner of speaking gives us a scene that's densely layered with words and ideas. There's so much to process and the first time I watched it I felt like the scene just washed over me in the theater, like a half-understood college lecture given by a pedantic professor with a penchant for adverbs ("assiduously," "inexorably.")

Was Neo a clone? Had he been genetically engineered? Or were they still inside the Matrix? Was Zion just another level of the system, a dream within a dream? Was that why Neo was able to manifest his powers outside the Matrix at the very end of the movie?

These were the kinds of questions my friends and I were left to discuss as we exited the theater and talked amongst ourselves in those pre-Reddit days. In a way, this brought us back to Trinity's quote from the first movie: "It's the question that drives us. What is the Matrix?"

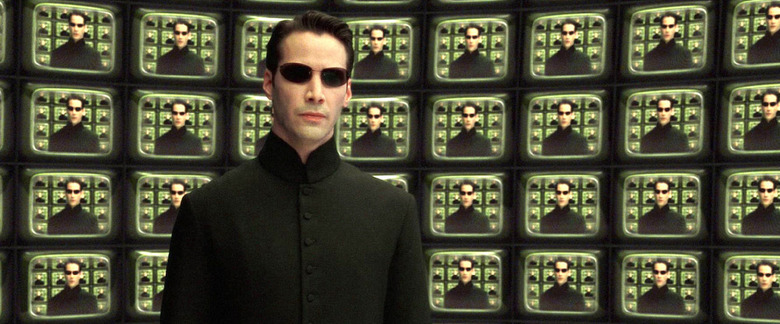

Levels upon levels, loops within loops. The faces on the monitors in the Architect's room seemed to imply that the previous Ones all had the same face as Neo, and the first movie did tease us with the sight of "fields, endless fields, where human beings are no longer born, they are grown." Neo had supposedly never even used his eyes before he was woken up from the Matrix. If he was grown like a vegetable, it's feasible he was one of many who looked exactly alike. Or, if Zion was, in fact, inside the Matrix, it's also possible that Neo's "residual self-image," the mental projection of his digital self, was merely programmed.

You could even read the scene as a critique of the white savior narrative. It seems more likely, however, that the images we see on those monitors are just the system predicting Neo's responses, mapping out every possible reaction, like the one where he says, "Bullshit," and the monitors synch up because "denial is the most predictable of all human responses."

We had no way of knowing back in May of 2003. The movie raised a host of mind-bending questions, and even though its sequel would endeavor to show how Neo answered those questions himself, manufacturing his own new meaning out of the ashes of the old narrative, there was almost no need for that because the effect was already achieved. If Neo is an audience surrogate, then The Matrix Reloaded rewrote the story and left fans dangling in a way that allowed them to construct their own elaborate theories for where the narrative could or should go or what it all meant. In a sense, this freed us from the Matrix of the movie itself. We became our own actors in a cerebral, existentialist, real-world game of mind theater. We'd been told the meaning of the story; we'd seen that meaning fall away; now we would have to use our own brains to determine what new meaning, if any, there was.

That's almost a parable for the mystery of life itself. The Matrix Reloaded is a film that's deliciously enigmatic and arguably more in touch with the true cognitive experience of living than its predecessor, because it offers no easy answers but instead takes us back to a place where an unresolved hunger — the eternal question of meaning — is once again driving the story. Though the movie ends with a cliffhanger, I've always been inclined to regard it as part of an unfinished masterwork and just pretend The Matrix Revolutions never existed. That's a unique take, no doubt, but in my own head, the movie is complete in its incompleteness.