Denzel Washington Is The Best Actor Ever

(Welcome to Best Actor Ever, an ongoing series where we explore the careers and performances of the greatest performers to ever grace the screen.)

If the young Denzel Washington had his way, the now 68-year-old Mount Vernon native would have a bust in Canton's Pro Football Hall of Fame. The man who would be Malcolm X, Rubin Carter, and Alonzo Harris initially had his sights trained on the gridiron before he enrolled at Fordham University in 1977, where he was a skilled enough athlete to play under Coach P.J. Carlesimo for the school's junior varsity team. "He would run us all day, and make us work," Washington told the New York Times in 1998. "But you know what? We were always prepared for the fourth quarter, and we hardly ever lost. Some of the things I learned from him, I still apply myself."

Washington knew by this point that a pro sports career was well out of reach, and he struggled to find a new calling until, at the age of 20, he attended a performance of Sophocles' "Oedipus Rex" at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Manhattan. James Earl Jones' portrayal of the prideful king knocked the young man sideways. After the performance, he snuck into Jones' dressing room and marveled over the commanding actor's props and rings. As Washington told Oprah Winfrey in 2007, he thought to himself, "One day, I'll make $650 a week and work on Broadway."

Origins

By the time Washington made his Broadway debut in Ron Milner's comedy "Checkmates" (alongside the formidable trio of Rudy Dee, Marsha Jackson, and Paul Winfield), he'd already been nominated once for an Academy Award (as South African activist Steve Biko in Richard Attenborough's "Cry Freedom"). One year after Milner's play closed in December 1988, Washington would be on the verge of stardom due to his fiery portrayal of slave-turned-Union-soldier Trip in Edward Zwick's "Glory." He won his first Oscar for that performance several months later, and wouldn't return to Broadway until 2005, by which point he was earning $20 million per picture as one of the finest actors on the planet.

This is because there is no such thing as a bum Denzel Washington performance. You never see him straining for effect. He is, by dint of sheer charisma, electric in every scene. But there's always more bubbling under the surface with Washington. That is the residue of preparation. With the possible exception of James Cagney, no one has ever gone harder in every single film than Washington. He's dedicated to his craft, fiercely in the moment, and always, always ready for the fourth quarter.

The prelude to stardom

Washington was hardly an unknown quantity when he attained full-fledged movie stardom in 1989. He'd earned enthusiastic notices for his portrayal of Private FC Melvin Peterson in both the stage and film productions of Charles Fuller's "A Soldier's Play" (retitled "A Soldier's Story" for the big screen), and was an impressively steady presence as Dr. Philip Chandler over six seasons of NBC's superb hospital drama "St. Elsewhere." As for Washington's 1981 film debut in Michael Schultz's tone-deaf racial satire "Carbon Copy," he's the only member of the cast (which included George Segal and Susan Saint James) who escaped with his dignity intact.

When Washington was cast as Biko in "Cry Freedom," those who knew the slain anti-Apartheid activist's tragic tale (conveyed with searing outrage in song by Peter Gabriel) expected an unforgettable cinematic experience. Alas, Attenborough and screenwriter John Briley (both white) bizarrely opted to focus on British journalist Donald Woods (Kevin Kline), who fled South Africa to bring Biko's story to the world. Washington is galvanizing in the part, but he's dead by the midpoint of the movie. Worse, there's no texture to the character as written; he's a black saint who would've been forgotten if not for the bravery of a white savior reporter. Gabriel's seven-minute song is more illuminating.

Washington lost the 1987 Best Supporting Actor to Sean Connery and spent most of '88 working on Broadway in "Checkmates." Still, his star potential was undeniable. The breakthrough seemed inevitable; it was just a matter of getting him in the right role. Zwick, who'd also made a name for himself via a hit TV drama ("thirtysomething"), had the flashy, awards-friendly supporting part for Washington in "Glory," but Swiss commercial director Carl Schenkel and "Blade Runner" screenwriter Hampton Fancher had a meaty leading-man character teed up for the young actor in "The Mighty Quinn."

The breakout

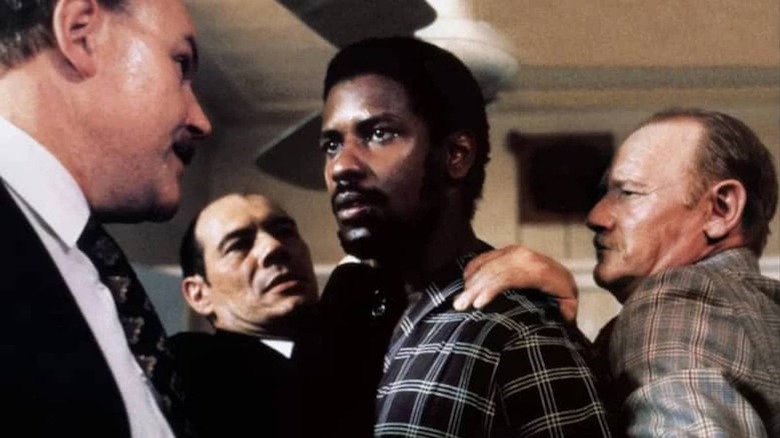

This nimble Carribean-set neo-noir about Xavier Quinn, a police chief who believes his childhood best friend Maubee (Robert Townsend) has been framed for murder by the island's corrupt operators, played directly to Washington's strengths. Quinn is smart, principled, and dead sexy. He's a living legend on the island. They call him "The Mighty Quinn," a nod to the Bob Dylan song made popular by Manfred Mann. Quinn resents the hero worship. He just wants to do his job. But clearing Maubee of murder will take a heroic effort. Quinn must work his connections, outmaneuver the venal bad guys, and resist the enticements of a millionaire hotelier's bored wife (Mimi Rogers).

In a typical noir, Quinn would be anything but mighty. He'd be susceptible to corruption, and likely lured to his doom by Rogers' femme fatale. But Schenkel and Fancher slyly subvert these expectations. Quinn has every opportunity to be a dirty cop and an unfaithful husband. There is a seduction scene between Washington and Rogers that ranks as one of the hottest non-sex scenes in film history. These two want every single inch of each other. We fully expect them to take it to the bedroom, but they walk it right up to the brink of consummation before backing off.

At this point, Quinn feels defeated. He gets loaded and drops by a local bar to drown his frustrations. Quinn takes a seat at a piano and launches into a blues standard. He's scraping bottom. The patrons, his friends and neighbors, watch him with a seeming mix of pity and disappointment. In a comforting gesture, the tavern's house band takes the stage and hijacks the tune – it's "The Mighty Quinn." Our hero appears ready to stumble out of the establishment until Isola (Tyra Ferrell) places a steadying hand on his shoulder. This isn't ridicule, it's love. They believe in him. Quinn is handed a bottle of rum and joins in the revelry.

"Glory" might've won Washington the Oscar, but for those of us who saw "The Mighty Quinn" first, he won our hearts forever with this blindingly brilliant movie star turn.

The first phase of stardom

Washington was clearly a star after his Best Supporting Actor win for "Glory," but he needed a box-office smash to make it official. His first collaboration with Spike Lee, the jazz drama "Mo' Better Blues," was terrific, but failed to catch fire commercially. The wildly divergent 1991 duo of Mira Nair's lovely romantic drama "Mississippi Masala" and Russell Mulcahy's gleefully unhinged actioner "Ricochet" introduced us to the two Washingtons (serious actor and action hero), but neither packed 'em in at the multiplex.

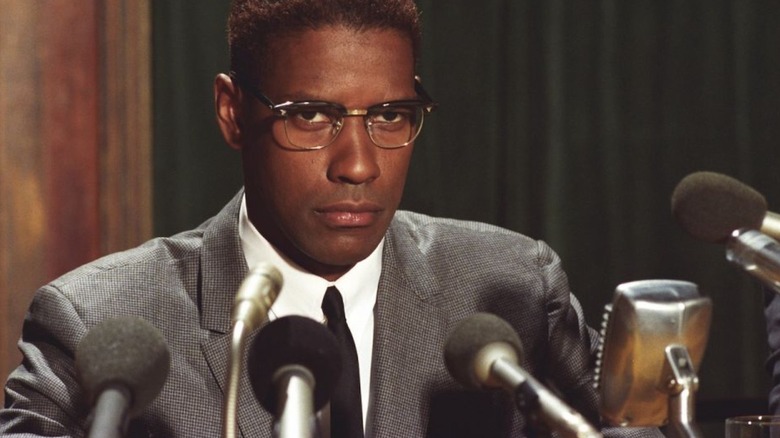

Washington wasn't considered bankable when Lee cast him as the complex Black Muslim leader Malcolm X. Indeed, the film was viewed with such skepticism by Hollywood that the filmmaker was forced to raise money from notable Black celebrities like Oprah Winfrey, Bill Cosby, and Michael Jordan to realize his vision. There was some (very dumb) critical grousing about the film when it was released, but no one could deny that Washington was masterful in the title role. He would've won Best Actor that year had the Academy not felt obligated to atone for overlooking Al Pacino in 1974 for "The Godfather Part II."

I have no idea if this is the case, but agents have a tendency to protect their major earners who aren't reliable draws on their own by booking them in two-handers. So when I look at Washington's post-"Malcolm X" run in the 1990s, I wonder if this is why he was paired with Julia Roberts ("The Pelican Brief"), Meg Ryan ("Courage Under Fire"), and Whitney Houston ("The Preacher's Wife"). When Washington was the solitary star draw, you got the ho-hum returns of "Virtuosity," or an outright bomb like "Devil in a Blue Dress." The latter is now considered a classic noir, and should've launched a series of films based on Walter Mosley's private investigator Easy Rawlins. The lily-white leadership at Sony, however, had no idea how to market the movie, which killed that franchise in the crib.

Denzel ascendant

Washington's first $100 million grosser sold entirely on his name was Boaz Yakin's uplifting high-school football drama "Remember the Titans." This commercial triumph arrived one year before Antoine Fuqua's "Training Day," where Washington indulged his inner demon and dazzled/horrified us with the law-enforcement flipside to Xavier Quinn. Detective Alonzo Harris is a monster, one who, according to the star, eluded punishment in screenwriter David Ayer's original screenplay. Washington, a huge fan of James Cagney, believed Alonzo should reap the whirlwind, and that's why the character takes a hot-lead shower before the credits roll.

Once Washington had the cachet to topline movies solo, he prioritized mainstream entertainments with a serrated edge. "Man on Fire," "The Manchurian Candidate," and "Inside Man" are all expertly crafted action-thrillers from three of the best directors to ever do it (Tony Scott, Jonathan Demme, and Spike Lee). Washington was particularly in sync with Scott's spatially controlled chaos, and gave Oscar-worthy performances in "Man on Fire," "Déjà Vu," and "Unstoppable" as well. As he nears 70, he's used his clout to bring August Wilson's stage play "Fences" to the big screen, and played Macbeth opposite Frances McDormand for Joel Coen. "The Equalizer 3" is also on the way. He is, like almost every great movie star, serving his needs and his fans' needs, but he does the latter with enough aplomb that you don't mind. He's far from done. But he'll have to dig deep in the fourth quarter to top what remains his crowning achievement.

The defining performance

It wasn't intentional, but Spike Lee did Washington a huge solid on "Malcolm X" by placing himself at the forefront of the production. Lee is a natural, incorrigible salesman. While navigating a white-as-Pat-Boone Hollywood in the '80s and '90s (and even now), he had to be. His first five films performed well on their own terms, but the studios always hedged their bets with their release strategies. If a Spike Lee movie found its way into a non-urban market, it was in second run. This meant there was a built-in budget cap on his films; ergo, if he was going to make an epic out of "Malcolm X," he had to go full Barnum.

Once he knocked Norman Jewison off the project, Lee applied a full-court marketing press on the public. "X" ball caps were ubiquitous in the build-up to the release. He granted loads of interviews, and sold himself as the only filmmaker alive who could do justice to the murdered leader's story. "Malcolm X" was Spike Lee, and Lee was "Malcolm X." As for the guy playing "Malcolm X," even though he'd been nominated for two Academy Awards and won one, he was on the periphery. The heat was on Lee. This allowed Washington to keep his head down and become his character.

But not in a method sense. Washington studied Malcolm, worked with Nation of Islam advisors, and learned how to march and carry himself as they did. But when he went home at night, he did so as Denzel Washington. This is his process. All that matters is what you do on the day — the Cagney way. As he once said, "There's not much to say about acting but this. Never settle back on your heels. Never relax. If you relax, the audience relaxes. And always mean everything you say."

A revolutionary portrayal of a revolutionary

Washington never relaxes, not even in a paint-by-numbers programmer like "The Equalizer 2." But in "Malcolm X," he's a taut wire in every scene. Whether he's a numbers-running hoodlum or a highly educated religious leader, he's primed to snap. The tension of Malcolm's existence, his righteous fury and compassion for his people, is almost ungovernable. For a brief time, he has a stirring command of his adherents, but the weight of his responsibility and the dawning knowledge that his mentor, Elijah Muhammad, is a fraud leaves him trapped. He never backs off his principles, even as the world closes in on him. His long, lonely walk to the Audubon Ballroom, where he will be murdered, is especially brutal because all he's done, as far as the movie is concerned, is attend to the needs of his followers. Washington accesses that isolation with a haunting stillness.

The carousing, macho posturing, and soaring oratory come easily to Washington. We'd follow him off a cliff. It's the quietude, the sorrow that Malcolm can't bring himself to express because he can only be a rock to his people — that guts us. The aftermath of the assassination, the weeping and wailing in that nearly empty ballroom, the profound loss of a righteous seeker who was mid-metamorphosis ... it just wipes you out.

Washington took us on a remarkable journey. It's one thing to read "The Autobiography of Malcolm X" (and that's a thing you must do), but to see how a person can find not only salvation in faith and education, but purpose in the blending of the two is a gift. Sometimes I think "Malcolm X" is the greatest of all American movies, and it would not be thus without Washington. I've seen superb portrayals of Malcolm (from Mario Van Peebles, Jason Delane, and Kingsley Ben-Adir), but the fullness of Washington's performance is unmatched. It's the fourth quarter and overtime. It's the entirety of the human experience in three hours. It's the greatest feat of acting I've ever seen.