Star Trek: Discovery Never Quite Worked – Because It Rejected Core Star Trek Ideas

When CBS All Access — now called Paramount+ — first debuted in 2017, it was a big deal. Not only was there a new contender in the ongoing Streaming Wars, but a long-moribund entertainment franchise, "Star Trek," was going to return to TV for the first time since the cancelation of "Star Trek: Enterprise" in 2005. In 2006, there was a kerfuffle within Viacom, Paramount's parent company, thanks to the scandal over Janet Jackson's infamous wardrobe malfunction at the 2004 Super Bowl Halftime Show. The fallout from that incident saw Viacom splitting between an arm that owned CBS, Showtime, and the WB, and the arm that owned Paramount Pictures, BET, and MTV. This meant that one studio owned the rights to "Star Trek" movies, and the other owned "Star Trek" on TV.

In 2009, Paramount managed to make a legally distinct version of "Star Trek" in the form of J.J. Abrams' Kelvin Timeline movies, while the CBS arm began spreading Trek widely on DVD, Blu-ray, and any streaming service that would have them. Continuity-obsessed Trekkies began arguing endlessly about what constitutes "real Star Trek."

The 2017 launch of "Star Trek: Discovery" was meant to be a return to "proper" Trek. The Abrams features were entertaining, but they were action-based movies that openly rejected stalwart "Star Trek" traditions like diplomacy, real-sounding science, and a proper chain of command. "Discovery" was initially constructed by Bryan Fuller who had written for "Star Trek: Deep Space Nine" and "Star Trek" Voyager," and who conceived of the project as a prequel to the original "Star Trek." Anyone who was following the production of "Discovery" will also recall that it became a clusterf***, as more and more showrunners and producers became involved. Eventually, 20-some producers would be credited.

In short, "Discovery" was a mess from the start.

How it all started

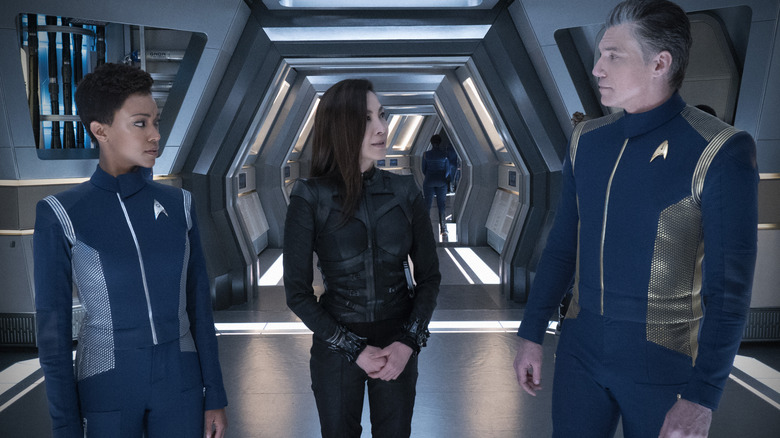

"Star Trek: Discovery" immediately felt ... off. The first episode of the series, "The Vulcan Hello" (September 24, 2017), changed a lot of premises that seemed out-of-character for "Star Trek." For one, the central character, Cmdr. Michael Burnham (Sonequa Martin-Green) was said to be the adopted sister of Spock. Surely if Spock had a sister, he would have mentioned it in previous TV shows or movies, yes? Additionally, "Discovery" began right at the hasty beginning of a war between the Federation and the Klingon Empire, plunging Trekkies into the one event — war — that "Star Trek" was previously very careful to studiously avoid. The Klingons were massively redesigned, looking like an entirely new alien species, and, quite crucially, the U.S.S. Discovery had the ability to teleport anywhere in the universe, thanks to a massive network of microscopic interdimensional spores. One might give the show credit for exploring the outer bounds of Trek tech, but it seemed implausible, even by the standards of Trek's usual fantasy machines.

But an open mind was required. "Star Trek" was pushing into new territory, and Trekkies needed to remind themselves that massive redesigns and new ideas will necessarily come along every once in a while. Perhaps this will merely be "Star Trek" with a new tone.

But then, even after a season, the show didn't manage to find its footing. It sped through massive events too quickly and the characters were constantly operating in panic mode. Only the basest lip service was paid to sci-fi pseudo-science. The show focused so much on the characters and their immediate emotional reactions to constant violence that it failed to establish the vital, mature formalism commonly associated with the franchise.

What is everyday life like on the U.S.S. Discovery?

One of the vital errors of "Discovery" was its deliberate rejection of traditional "bottle" episodes. "Star Trek" is, perhaps beneath everything, a workplace drama. The above-mentioned formalism strings from a workplace power dynamic wherein different experts in different departments have to answer to managers and captains, all working together to solve complex sci-fi problems. How a captain gets along with her crew is a common theme across the entire franchise, and watching smart people do their jobs on a workaday basis provides many Trekkies with a particular, structure-seeking thrill.

"Discovery" was a violent action series that never depicted its characters having a regular day. The drama ran too high, and the incidents came too quickly. In the second season, the Discovery teleports across the galaxy to investigate a series of mysterious signals left behind by an angel-shaped time traveler. At the head of the season, it's said there were seven signals to investigate. The show became so involved in battles and races against time that it didn't even bother to find all seven signals. It's such a busy show that it can't even finish its own stories.

With the characters constantly in crisis mode, their dynamic changed into one of weepy desperation. Before too long, Michael Burnham was turning to Saru (Doug Jones) or Ens. Tilly (Mary Wiseman) and crying about how grateful she was to have them as her family. I suppose when one is constantly looking death in the face and committing murder as a response (everyone on "Discovery" commits murder), it might create a death bond of sorts, like soldiers in a trench. This weepy death bond, however, was quite different from previous Trek shows, where characters bonded over professional respect and their abilities to work together.

The time shift

Also, throughout all of "Discovery," the series never once addressed the massive sea change that teleportation technology would have on an organization like the Federation. If ships now had the ability to instantaneously appear anywhere in the universe, wouldn't that fundamentally alter everything about the way society operates? It seems that the showrunners merely wanted to cut down on "down time," and eliminated any period wherein characters traveled from point A to point B.

They essentially eliminated trekking from "Star Trek." Gone, then, was any sense of cosmic scale. Again, the show narrowed in too closely on its characters.

At the end of the second season, the showrunners invented a wise conceit that explained away why the U.S.S. Discovery, its crew, or its teleportation, was never mentioned in the previous shows. It seems a malevolent machine intelligence infected the ship, and if anyone broadcast any information about said intelligence, it could spread and take over the galaxy. The Discovery flew through a time portal and wound up nearly a millennium in the future. Back in the present, Starfleet issued orders to strike the Discovery from all historical records. The canon is now clean again.

In the future, the Federation was wounded after a galaxy-wide cataclysm destroyed almost all the starships. But even as the Discovery met with a future Starfleet, received upgrades, and looked a little more closely at its own tech and Starfleet's place in a wounded galaxy, it still never spent enough time on the Discovery itself.

One might think the show would begin devoting itself to 1,000-year-old officers climatizing themselves to new rules and tech, but it was still too action-forward and badly written. Even with a new ship, "Discovery" did not settle in.

What 'Discovery' does right

The twist at the end of season 3 was that the galaxy-wide cataclysm — called the Burn — was inflicted by a single innocent with god-like powers, unaware that it was doing harm. In the fourth season, there is another widespread cataclysm and it was inflicted by a species of innocents with god-like powers, unaware that they were doing harm. It seems "Discovery" found a groove.

So, ultimately, the central error of "Discovery," and the reason many Trekkies didn't connect with it, is that it attempted to eliminate trekking from its own formula. In so doing, it eliminated a variety of missions. It eliminated a need to establish protocol and a group dynamic among the crew. It eliminated the need for diplomacy. There were no ethical dilemmas to work through. It was all violence and sadness. And while violence and sadness have their place in "Star Trek," it shouldn't have been its basis.

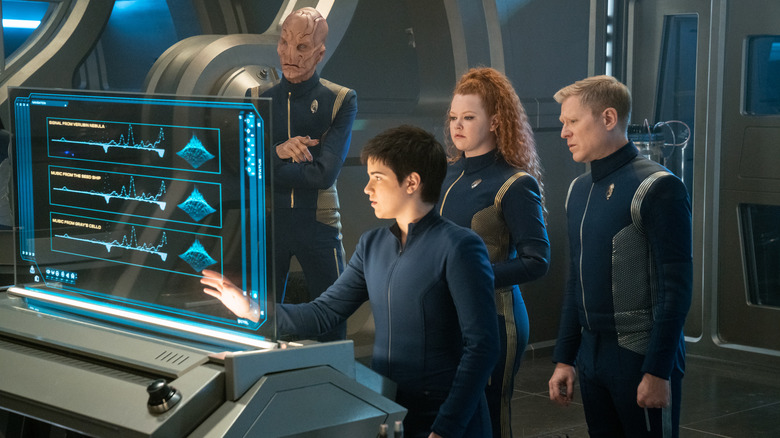

I would, however, be remiss if I didn't state some of the things "Discovery" did amazingly right. In terms of representation and depicting a utopian crew of varied humanity, "Discovery" was first-rate. In addition to featuring a Black woman in the lead, there are no less than four openly queer characters. Dr. Culber (Wilson Cruz) and Lt. Stamets (Anthony Rapp) are happily married, and have adopted a non-binary child named Adira (Blu Del Barrio) who is, in turn, in love with a young man named Gray played a trans/masc actor (Ian Alexander) who uses they/them pronouns. Trek wasn't always great about queer representation. Here, they are happy to be open about it. This was done 100% right.

But without protocol and without a workplace dynamic ... well, "Discovery" still doesn't feel like "Star Trek." Perhaps its fifth and final season will rectify that, but to date, the show never filled its potential.