A.I. Has Hollywood Voice Actors Trapped Between Peril And Possibility

In 2021, director Morgan Neville made headlines when he revealed that he and his team had built an AI model of the late Anthony Bourdain's voice for his documentary "Roadrunner," and Neville had secretly slipped AI-generated narration into the doc alongside narrations that Bourdain himself actually read aloud. In this case, the AI narrations were for lines the acclaimed chef and television personality had written in books or articles but never physically recorded ("We were merely trying to articulate things he had already said," Neville explained), but controversy swirled about the ethics of that decision.

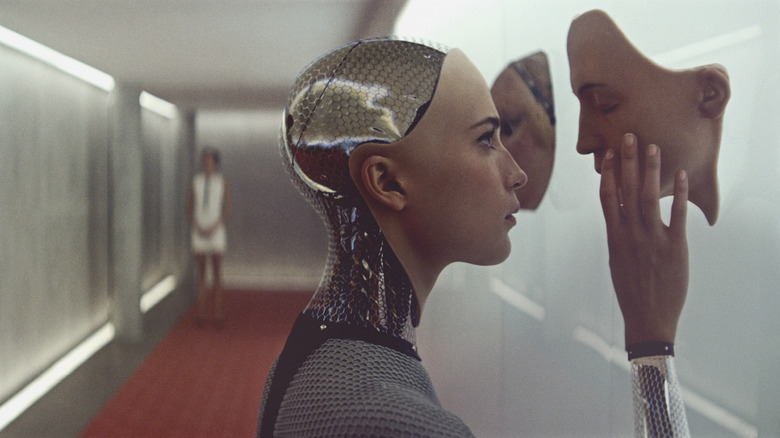

In 2022, actor James Earl Jones, who has provided the voice of Darth Vader since the original "Star Wars" in 1977, made his own headlines when he allowed a start-up company called Respeecher to use artificial intelligence to generate new vocal performances using his early archival recordings as source material, letting Lucasfilm retain a consistency to Darth Vader's iconic intonations instead of recasting the role. Jones, now 92 years old, reportedly provides guidance and advice to the teams working to keep Darth Vader at the forefront of pop culture. After 45 years of existence, Darth Vader has become a more synthesized combination of man and machine than ever before.

Over the past nine months, artificial intelligence has exploded back into mainstream conversation, with AI art generators (or, more accurately, art stealers) like Lensa sweeping across Instagram and generative AI tools like ChatGPT taking the idea of chat bots to the next level. But the James Earl Jones news raised questions about what impacts AI might have on the voiceover community as a whole. If archival recordings can now be fed into a computer that can create brand new line readings, have we entered the final days of human artists being paid to do voice work for studios and production companies?

/Film spoke with some of the biggest and most prolific voice actors in the country to try to answer that question.

How the technology works

You've likely seen split-screen videos of actors wearing motion capture suits performing on a soundstage alongside the fully rendered image which appears in the final product. This AI technology for voiceovers works in a similar manner, only with audio.

"They'll hire an actor to basically be a puppeteer for the James Earl Jones voice," explains Keythe Farley, an actor and voiceover director who has credits on the Mass Effect games, "Adventure Time," and Cyberpunk 2077. "So the actor's performance will then get 'skinned' by James Earl Jones' [AI-generated voice]." And it's not just celebrities who provide those "skins," or customized voices that are overlaid onto a baseline performance.

Abigail Savage has appeared on shows like "Orange is the New Black" and "What We Do in the Shadows." She's uniquely positioned to talk about this technology, because she's not only an actor, but she's also been working as a sound editor and sound designer for over 20 years. She's worked closely with Respeecher, the same company that Lucasfilm teamed with for the new Darth Vader vocals, and was "smitten" with what the technology was able to do.

For a project Savage was working on that planned to utilize this technology, Respeecher had to recreate someone's voice, and in her estimation, it "seemed to have jumped over the uncanny valley into something that was quite usable and realistic and incredibly impressive." That particular project ended up not coming to fruition, but she was so taken by what the company was able to accomplish that she became a beta tester for its voice marketplace program.

"They have a bunch of pre-set AI voices they've developed [using] synthesized other human beings, so the voices aren't actual individuals, but are amalgamations of people. It's a way to record yourself saying something and choose whatever voices you want from their marketplace. Then it outputs those voices with what you said, and it maintains your performance but through another voice. That's something that's just great for a sound editor who's doing things and needs the occasional line said. It used to be you'd just spend a night doing group loop, which you'd get a bunch of friends and some pizza and you have people come into the booth and say the one random line that you need covered. Now, I can do it all myself, which is just, frankly, awesome."

Are voice actors about to become obsolete?

/Film reached out to Nancy Cartwright, who has provided the voice of Bart Simpson for more than 35 years. She responded to questions via email, and has faith that voice actors will not be replaced by artificial intelligence.

"Ultimately, the true magic of performance lies in the human element and the nuances can never be replicated by technology alone," she wrote (emphasis hers). "In many ways, it is faster and easier to get a performance out of a person, rather than a machine — like when I am being directed on an animated show. I take the direction, change my voice, and even ad-lib — something a machine cannot do. This is what truly separates just a 'sound' [from something that gives] life to the artwork ... I believe that technology can enhance the voiceover profession rather than make it obsolete."

The importance of the human element was a recurring refrain from the people we spoke with for this article, including Billy West, who was the voice of Fry on "Futurama," Doug Funnie on "Doug," and Bugs Bunny in the original "Space Jam."

"You can't replicate the acting," he says. "You can't replicate the original artistry, the original synapses ... they can't steal your mind or how you interpret things ... you could use it to the extent where it would be touches here and there and nobody would know the difference. But if you're going to let everything rest on that technology, they probably have a long way to go."

"They could not sample Michelle Yeoh, and create a CGI rendering of her, and recreate what she did in 'Everything Everywhere All at Once,'" echos Maurice LaMarche, who has over 400 credits to his name and is most famous for his work on "Pinky and The Brain," voicing Brain. "I don't care how advanced the AI technology, it doesn't have a heart. It doesn't have a soul. It doesn't come from within to know what will make a viewer cry, or make a viewer laugh."

If you've ever watched "The Powerpuff Girls," "Loki," or played the latest Batman video games, you've heard the voice of Tara Strong, a veteran performer with over 600 credits. She says she's been in studio sessions with actors who can perfectly mimic a legacy character, but despite their ability to capture a similar tonality, "they don't have the soul of that character." She thinks AI "will be able to mimic, I think they'll be able to star in movies, star in cartoons, maybe fool some people. But I don't think — and maybe this is Pollyanna of me — I don't think they're going to be able to capture the essence of someone who was born to be a performer."

The technology isn't there yet

Duncan Crabtree-Ireland is the National Executive Director of SAG-AFTRA, the labor union that represents actors across film, television, radio, and more. He's recognized an uptick in AI quality, but also doesn't think it has progressed to the point where AI could fully replace human actors. "I think any of us who've used text-to-speech technology know that it is a lot better than it used to be, but it's still quite limited," he points out. "If you imagine listening to the Harry Potter books with text-to-speech technology versus listening to the audiobooks of the Harry Potter books, which are full of artistry and really performed as much as they are read, those are two very different things. I can't tell you that it could never be the case in the future someday that AI technology couldn't attempt to replicate that performance quality. But it's definitely not there now."

Keythe Farley isn't fully buying it, either. "I don't think that AI is going to replace actors doing scene work anytime soon. They keep making these claims about how it can be emotionally viable, but I don't know how two AI actors play out a scene together in that regard."

While none of the people /Film spoke to believe voice actors will imminently be made obsolete, most acknowledged being scared or at least concerned about the implications of AI on their profession. "It's really terrifying how great the technology is getting, and I think it's super dangerous," Strong admits.

Tim Friedlander, a voice actor with credits on "Hunter x Hunter" and "One Punch Man," likens this new wave of AI technology to the long-term effects certain innovations had on the music industry.

"You look back at music, it's the same. 'Oh, well, synthesizers are going to make piano players obsolete, and loopers and samplers and digital interfaces audio is going to make performers obsolete.' And to a certain extent, we are now, 30 or 40 years later, where you can go to a performance and you'll have everything running off a Pro Tools rig and one singer [on stage] ... So it has eliminated an entire generation of performers, of musicians. Potentially, it's going to have the same impact here."

Even so, Hollywood has not raced to replace actors en masse — not yet, anyway. "The hope that we have, at least any kind of shining light, bright light in this, is that producers still want a human person to direct," Friedlander says. "They still, for the most part, don't want to replace human voice actors, if it comes down to the performance."

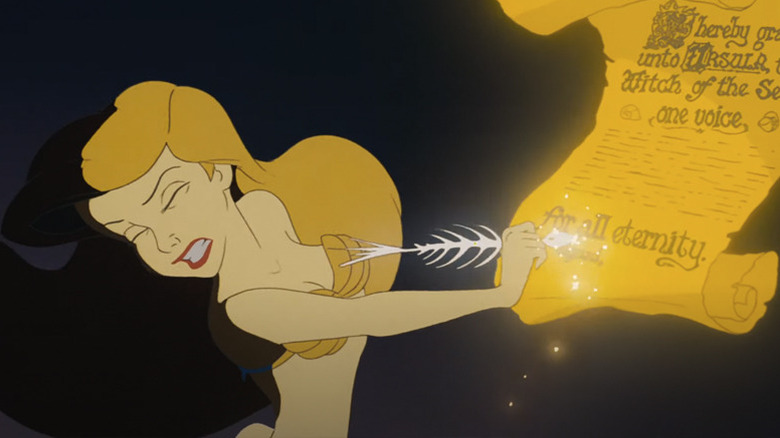

"It's all about how clever the voice actor will get with what they were born with and what tools will exist in the future," Nancy Cartwright writes. "Innovating rather than fighting change is a good perspective to keep in mind. I believe that the artist can and will always find ways to use technology to create, rather than simply allowing technology to dominate them and make their art form a thing of the past."

"By the way," she adds, "the derivation of 'animation' is 'a bestowing of life ... filled with breath ... make alive ... spirit' — something unique to the artist and not a machine."

The intangibles

Try as it might, there are some things technology simply cannot do as well as a human. In Jon Favreau's 2003 Christmas classic "Elf," there's a scene in which Will Ferrell's character, Buddy the Elf, chugs a two-liter bottle of Coke and, a couple of minutes later, lets out a comically long belch. After a failed attempt to use computers to produce the burp, the production hired Maurice LaMarche to provide the vocal effect.

"The filmmakers had tried using the technology they had to cobble together digitally several long burps," he explains. "They needed 15 seconds. What they came out with, there were no nuances of speech or emotion to it. They couldn't get a convincing-sounding 15 second-long burp. Now I do something with my throat. I've done it since fifth grade. It's a combination of Tuvan throat singing technique, where you just rasp your voice at the very lowest note it'll go to, and [a tongue move]. You're making echo chambers in your cheeks by doing that with your tongue. You combine that, and you get [makes loud burping noise]. And just hold that for 15 seconds. Because a human being did it, a human being with a sense of humor, and more important, a sense of comedy — because I was really trying to crack up the recording engineer as I was doing it — you got the result of what cracks people up when they watch 'Elf' every Christmas."

Another thing computers can't do effectively is ad-lib. Bart Simpson's famous "eat my shorts!" catchphrase spontaneously sprang forth from Nancy Cartwright during a table read. That intangible aspect of voice acting and performance was also underlined by several members of the community, including Candi Milo, who has nearly 300 acting credits; she recently worked on the reboot of "Animaniacs" and previously voiced the title character in "Dexter's Laboratory." She tells us, "We all miss group records because you miss reacting to, and laughing with [other people], and thinking of ad-libs ... there's nobody to react to. There's nobody there that says something funny so you can do an ad-lib, and it misses that natural pace, that natural energy, that natural vibrancy."

Meanwhile, LaMarche recounts an instance in which he employed a trick he'd heard from another actor, incorporating an element to his performance that a computer never could. "I delivered every Lexus commercial to my best friend. I pictured them in the corner of the booth, on the other side of all the ad people and the creatives, in a little chair in the corner. I told them to keep it empty. I delivered every Lexus commercial to my best friend. I think that's what made my run as that voice so successful. An AI doesn't have a best friend to talk to."

Possible upsides to artificial intelligence

While artificial intelligence may seem like an existential threat to the voiceover profession, several of the people /Film interviewed are trying to find a silver lining. In Nancy Cartwright's view, "[AI technology] could provide more opportunities for voice actors and make their performances more accessible to a wider audience by learning how to create artificial changes to their voices or adding nuances to their voices that they couldn't perform physically before — for example, speaking in a higher or lower octave or accent."

That accent example is currently being put into practice at a company called Veritone. Working with clients like NCAA, the Australian Open, The Masters golf tournament, CBS News, and hundreds more, Veritone uses AI in several different ways, but over the last year, they've become a significant player when it comes to synthetic voices. Co-founder and CEO Ryan Steelberg believes every voiceover artist should have their own versions of their synthetic voice created. Then, each artist can essentially become their own boss by overseeing an AI model of their voice which can produce more sessions in a day than a human could physically record — and speak in languages the human artist can't actually speak.

"Voice talent is not just the sound of their voice," Steelberg says. "Voice talent and voiceover is how effective they are in speaking. Right now, we can create great-sounding clones, but how the presentation of that voice is melded with and into a production is still a talent. Our position with voiceover talents is we embrace them. We have lots of voiceover talents as customers. We create synthetic voices, and we help manage those voices for them. They need to view this as a tool ... You take a great American English voiceover talent. Tomorrow, they can set up shop and offer their voice and their capabilities of, ironically, voicing their voice in multiple different languages. We can actually help bring a lot more business opportunity for voiceover talent by them investing and being willing to work with synthetic models."

"The Price is Right" host Drew Carey recently experimented with using an AI-generated model of his voice during a portion of an episode of his SiriusXM radio show, and after it didn't go over particularly well, he said he wouldn't be using it again. The technology may not be quite advanced enough to take over hosting duties for a radio show yet, but imagine an artist being tasked with recording a large number of hyper-local radio spots. ("You're listening to the Big Ape, 95.1, WAPE, Jacksonville's number one hit music station.") If that artist has a synthetic version of their voice (and if they reach an agreement with their employer), they could farm out those hundreds of recordings to the AI model and sit back while the check rolls in. The same thing applies for an artist hired to record audio versions of articles on websites, or to narrate audiobooks.

There are practical uses for this in the sports world, as well. One of Veritone's clients is soccer announcer Alan Smith. For the World Cup, the company used an audio clone of Smith's voice to do real-time announcing for hundreds of games that he wasn't able to actually voice himself. Using the same real-time data that powers box score updates, the clone of Smith's voice can read that data and do play-by-play commentary for a match the real man has never even seen.

'It's time and it's money'

In addition to using synthetic copies of actors' or celebrities' voices, remember that companies like this can also generate totally new voices as "skins" for additional line readings. Ryan Steelberg offered a practical example of how that could be used going forward. If a company wanted to set up a tip line about mental health issues, he and his team could design a voice they think could be soothing and empathetic to the callers in an effort to help calm any anxiety they may have.

"Voiceover talent has historically been using their own voice as their asset," he says. "They need to start thinking of their expertise of all things voiceover and looking at these tools because companies are doing it right now. And voiceover talent, they actually are in the driver's seat right now. They understand the industry. They understand the boards, [industry marketplace] Voices.com, how to get the jobs out there. When there's an opportunity, they need to be able to apply for that job, if you will, by using all the tools at their disposal. By them just saying, 'I'm only going to use my real voice,' I don't think that makes a lot of sense."

For Abigail Savage, that skinning AI technology simplifies things and allows a film or TV production to spend that money in other areas where it may be spent more effectively. "It's time and it's money," she says of the two greatest benefits she's experienced working with AI. "I can be the single microphone input for 20 different voices throughout a documentary that just needs occasional background conversation to fill in and create a realistic soundtrack. That's a lot more straightforward than asking 20 different people to come in and record one single line of audio and then trying to tease out a performance from them ... especially in my case, where I'm comfortable with the performative aspect of it."

Tim Friedlander identified a couple of other possible benefits. Instead of listening to article narrations through robotic-sounding text-to-speech voices, those with impaired vision could have a more enjoyable and authentic experience with an AI-enhanced version. The technology also has the potential to provide a literal voice for people who are non-verbal, allowing them the ability to customize the sound to match their personality.

"You're going to see premium talent who are embracing this," Ryan Steelberg predicts. "They're going to get a lot more work. And you're going to see, people who are not embracing this are potentially the ones who are going to be exited out of this industry."

But Maurice LaMarche isn't aligned with Steelberg's stance that all voiceover performers should have an AI model made of their voice. "No, I can't see that happening. Why? Because I can already do it. I enjoy making my voice do my bidding. I enjoy becoming ["Futurama" character] Lieutenant Kif Kroker. I don't want to push a button and hear Lieutenant Kif Kroker come back at me. I can just record me saying that, and go, 'Oh. You know what? That I can do that better.' It's retakes and retakes until I think it's funny enough. You should see how many times I do a Cameo, until it's funny enough. A computer doesn't know when it's funny enough."

Potential downsides

A prediction Steelberg could be right about, though, is that AI-generated voices may soon spell the end of so-called "soundalikes," actors who make their living by impersonating famous voices in a variety of official capacities. "[Tobias Meister] is the name of the voiceover talent who's famous for doing Brad Pitt's voiceover work in Germany," Steelberg says. "Those days are going to be numbered here. Brad Pitt and Tom Hanks and these people, when their show and their scene is being exported, it's going to be [an AI] version of their voice that's going to be speaking in [another language]."

It's funny Steelberg mentioned Tom Hanks, because the "Toy Story" and "Cast Away" star has actually had a secret weapon in the voiceover industry for years. Jim Hanks, Tom's younger brother, has been acting since the early 1990s and has credits on projects like "Robot Chicken," "JAG," and "Dexter." But he's also arguably the most famous soundalike in the world, having doubled Tom's voice as Woody from the "Toy Story" franchise since 1995. When you hear Woody's voice in toys, theme parks, video games, and Disney on Ice, you're hearing Jim's voice, not Tom's.

Since famous Hollywood nice guy Tom Hanks probably wouldn't create an English-speaking AI version of his voice that would take away work from his brother, Jim himself may not have to worry about being replaced. However, he knows others in his field may not be so lucky. "I think the soundalike industry is definitely vulnerable," he says.

Candi Milo has also done some soundalike work. "Part of the contract for a film is that you will do pickups or reshoots, but mostly audio pickups, as the actor's time allows," she says. "I cannot tell you how many times I have gone on a set because so-and-so won't do their pickups, or it's too expensive to fly Angela Lansbury in, so they hire somebody like me to go in and do two lines of her. That's how easy it is to do."

When Lansbury was in London during the making of "Mr. Popper's Penguins," the studio called Milo onto the Fox lot in Los Angeles to perform a couple of lines. She was paid a one-time fee and does not get residuals on the project, because she's not credited as an extra voice. This has been a common practice in Hollywood for decades, but AI models could conceivably bring that to an end.

And pour one out for all of the John F. Kennedy voice impersonators who have previously gotten work in movies like "Transformers: Dark of the Moon" and "Forrest Gump"; today, a production could work with the former President's estate and generate the lines they need using his actual voice as a foundation.

"If you want to reproduce a piece of history in a film, like a 'Forrest Gump' kind of scenario, maybe using the real JFK and using this technology to use his voice print to say, 'I believe he said he had to go pee,' maybe that would've produced a more convincing moment in the film," Maurice LaMarche concedes.

But Jim Hanks' concerns extend far beyond soundalikes. He suspects a rise in AI might lead to lower wages for all voice actors. "I've been in this industry long enough to watch earnings drop, because every time anybody who actually creates content on the producer end of it finds a way to pay talent less. So if you're going to allow people to use AI based on your voice, I suspect they're going to immediately go, 'Well, you're not going into the studio, so why should we pay you as much?'"

Regarding the examples provided earlier about artists licensing their AI voice to read hundreds of articles or audiobooks, Hanks doesn't imagine the outcome will be quite as rosy as it seems at first glance. "I can't imagine that those people would go, 'You know what? We want Morgan Freeman to read this article instead of this [text-to-speech voice],' because why would they pay somebody? They don't have to at this point."

Ethical concerns

Concerns about the morality of implementing new technologies are often as old as the technologies themselves, and AI is no different. The Bourdain documentary was a particularly thorny example, given that Bourdain's family members apparently did not give the filmmakers permission to use an AI-generated version of his voice. That was a creative-driven solution to an obstacle, but some corporate business practices are also being called into question. Two months ago, major audiobook distributor Findaway Voices came under fire after revelations that the company, which was acquired by Spotify last summer, was giving Apple the right to use Findaway's human-read audiobook narration files as training data for Apple's machine learning models. The problem was the voice artists who provided those recordings were not aware that their voices were contributing to that technology, and they did not give their permission for the recordings to be used in that manner. Apple and Findaway have since stopped the practice.

"I want to make sure that if I give permission for someone to use my voice, that I'm the one giving the permission and that I'm paid fairly for the use, that I have an understanding of how long my voice is going to be used and for what," Keythe Farley says. "I don't think there's anybody who's a performer out there who doesn't want to know that their voice or their performance or their image is being used in a way that they wouldn't consent to, whether that's moral or for any reason whatsoever. So it's just really about actors maintaining control over their voices as this new technology comes into the fore."

Jim Hanks recommends that voice actors take an extra close look at their contracts before signing on the dotted line. "I just recently signed a contract for something that I can't talk about. But in the first couple of negotiations, when the contracts were going back and forth, there was really specific language where they were saying that they wanted the right to use whatever I did and be able to manipulate it and make other things down the line. And my lawyer caught it right away, and I caught it too, [and] my lawyer went, 'No, that's not going to happen,' and they went, 'Okay, no problem.' But again, what I feel is what big business is going to do is they're going to try to slip that stuff in and hope that people don't notice it, and then go, 'Whoops, [it says] right here in this contract we can do it. You signed it.' So I think people definitely need to be aware of that."

In addition to his acting credits, Tim Friedlander is the founder and president of NAVA, the National Association of Voice Actors, an organization that has been trying to educate the community and arm voice actors with the proper tools to combat being exploited. He explained that NAVA hired a lawyer to draft a "synthetic voice AI rider that we have on our website that talent can put in to proactively hopefully protect against this going forward."

Keythe Farley is also a member of NAVA and has been involved with these education efforts. "What we've been putting out to our membership is basically if you go to work, and there's a standard SAG-AFTRA contract, [and] frequently there will be addenda to that contract, there'll be riders attached to that contract. If there's anything in those riders regarding synthetic use of your voice or your likeness — or your movement, if you're a performance capture performer — those clauses are what they call mandatory subject of bargaining, which means that until they have sat across a table and negotiated those terms, they're absolutely null, void, and unenforceable. So for actors in the union, what we've been counseling people to do is sign the contract, forward it to the union, and then let our lawyers go to work."

The organization's hope is that non-union actors will download their rider to attach to their contracts to ensure that no one's voice is being stolen and used without permission and compensation. Thankfully, it seems to be going well so far. "One of the things, at least that we're finding, the feedback we've heard from people, is that [many productions are] more than happy to add these in there, because they don't have the intention of synthesizing or digitizing somebody's voice," Friedlander reveals. "So a lot of people are having a lot of luck adding this into their contracts."

"We're looking to avoid any contract that says, 'You have the right to use my voice for anything you want to forever across all known media now or hereafter devised throughout the known universe,'" Farley says.

Questionable offers and a complicated system

Even prominent voice actors have had close brushes with sketchy situations. "I was approached to do a voice thing for an NFT project and they wanted to basically have me say a million different lines, really random things, and then they would teach this computer program to say anything in my voice," Tara Strong recalls. "And I said, 'So theoretically, they could make it say I hate a specific human, or type of human, or race, or say really terrible words that I wouldn't say in my real world?' And they're like, 'No, there are failsafes.' But let's be real a minute. Right? You can't really guarantee that."

Similarly, Maurice LaMarche says he was approached by one of the top studios to perform a particular impression. "They wanted me to basically read a telephone book into the microphone, and see if they could then create an animated character using the voice of the celebrity, who I presume refused to do this, and see if they could create this character with my very decent impression layering over samples of his real voice. They offered me a large sum of money, and I've turned it down flat. Do I think that stopped it in its tracks? No, but I would not be able to look at whatever the product was later and go, 'I helped with that.' I can't be the person that helped with that. I can't say, 'Well, they're going to do it anyway, so I may as well take the money and run.' I can't do it."

Unfortunately, there are plenty of people who would take that job (or one like it), especially people who are attempting to gain a foothold in the industry. Things can quickly become complicated.

"What you have is a cadre of underemployed actors that would be happy to replace you," Candi Milo laments. "They would be happy to do it, because they call it their way in. 'I've got my foot in the door, I'm just going to do this.' And I went, 'That is your entire body in the door. Because once you do that, there's no going back.' ... Screen Actors Guild, as a union to protect us, is so big and they're so disparate that [they're providing] different needs. Maybe I've done [the first entry in a franchise] and the studio wants to do part two and they don't want to pay more money, and I say, 'Fine, you can't use me, then.' But somebody says, 'Well, I want that job. They don't want Candi, and I want that job, and I can sound like her real voice, so I'm just going to do it.' Do they represent her, or do they represent me saying, 'I don't give permission for you to do this'?"

That constant fear of being replaced, relatable in so many professions operating in capitalist societies, is about more than just money for these performers. There's something indescribable that happens when an actor truly inhabits a role — something that can't be quantified, but can be felt by those who connect with the final result.

"There are definitely many times, particularly in voiceover, where the industry doesn't like to make you feel cherished as much as the fans do," Tara Strong says. "The [production] will say, 'Oh, we made this billion in toys' — which we don't have a backend on — 'and this billion on the movie, and we want to make the next movie and we want to give you guys scale and a half.' So you guys are making billions and you want to give us $2,000? [They'll say], 'Right, and if you don't do it, we're going to hire someone to copy your voice.' That doesn't feel so good. I don't know any actor that doesn't, especially in my world that I'm in every day, which is the animation world, put their heart and soul into something and feel very connected to a character. It's hurtful when they say, 'We could get someone else.' Because you really feel like once you are established as that character, it's a part of you. There's a part of me in everything that I do. That negotiation is a little soul-crushing. So I don't know that some genius company working with a Hollywood mogul would really give a s*** about honoring what a voice actor's created if they can mimic it."

Duncan Crabtree-Ireland specifically addressed a question many people had about the James Earl Jones scenario: Why didn't Disney just hire a replacement actor instead?

"That's a question that's impossible to answer, but what we can say is that so long as that work is being compensated and paid for, then the incentive to do it because of that is removed," he says. "So the company isn't choosing to do that because they're saving money. The company is choosing to do that because they believe they're getting the best creative output by using that iconic voice. And that is inherently a protection for our members, because if it's not being done for economic reasons, if it's being done for creative reasons and it's being done with consent and compensation, that preserves the whole range of other job opportunities that aren't tied to one particular performer's voice for everyone else. So really, I think establishing that principle that synthesized voices and AI voices don't translate into free work, that's the most important principle to help make sure our members are protected."

/Film reached out to multiple people at Skywalker Sound, but a senior publicist told us they are not able to participate in this story.

"I think that the misconception is that we are trying to stop this technology from coming into being, which is a fool's errand," Keythe Farley clarifies. "What we need to understand is that we are partners in this technology, and what the creators of this technology need to understand is that there are rules of the road, and that those rules need to be followed."

Deepfakes will continue to be a problem

Perhaps the most egregious and obvious example of not following those rules of the road comes in the form of deepfakes, which have been a problem for years. But this new AI technology provides new methods of abuse to the worst offenders online.

Duncan Crabtree-Ireland says the realm of deepfakes are where SAG-AFTRA has seen "the most egregious violations" of the rules, and Tim Friedlander cited a terrifying real-world incident that happened not long before /Film spoke with him for this piece. "A month ago or so, there were voice actors who were having their voices doxxed on Twitter, saying racist and homophobic things and giving out somebody's home address. Like saying, 'Hi, my name is so-and-so, here is my home address,' and then going on a racist tirade from there. It sounds like them. I mean, it sounds legitimately like, 'Oh, that sounds just like you. I know who you are.' And we're just the beginning of this. We're just at the beginning."

"They can have you saying things you never said," Billy West tells /Film. "They can stick your face on Johnny 'The Wad' Holmes from a porno film and put it on Twitter and go, 'Ah, here's your boy. Here's the guy you think is so great. He's a smut peddler.' That's a game people are just dying to play."

"I think people are hungry to get people canceled," agrees Tara Strong, who has experienced an AI company taking her voice and making her say "horrible" things. "I think that some people deserve to, but I think, by and large, a lot more are targeted that don't really deserve to. And I think that's going to make that even scarier."

"The worry is that anybody with a synthetic voice app can grab Bart Simpson's voice and then put it out saying and doing things that the actor might not be even aware of, and making money on it," Keythe Farley says. "And the other thing, too, is to be able to take that voice, Nancy Cartwright's Bart Simpson, and sell it to folks without Fox's knowledge and compensation or the actor's knowledge and compensation. That's where the rubber meets the road."

Billy West sounds disgusted by the lack of artistry involved with using AI technology. "What drives somebody to [devote their career to voice acting]? The love of the art. I think that's why it's never boring. That's why we never run out of passion or inspiration. I don't know how much passion or inspiration you need to be an AI artist or to swipe prerecorded tracks and mold it like it was Play-Doh."

Here's what's being done about these issues

The James Earl Jones news conjured nightmarish imaginary scenarios involving voice actors. Consider a situation in which 20th Century TV decides it wants to keep "The Simpsons" running, but when it comes time to renew Nancy Cartwright's contract, the network decides that instead of hiring her, it would rather tap into her old archival recordings and use AI to generate new line readings for Bart Simpson for future seasons. Thankfully, that won't actually happen, and Duncan Crabtree-Ireland explained why.

"All of those episodes of 'The Simpsons' that have ever been recorded since it started, and everything going back decades before that, is subject to a reuse of footage of photography and soundtrack provision. It's in our collective bargaining agreement. It basically says if they're going to make any kind of other use of the soundtrack or photography of any project, they have to negotiate with the performers who are involved and pay compensation as part of that negotiation process. So in that example that you gave, if they wanted to use that as the basis for creating an AI voice model and then using that for further projects, they would have to negotiate with her for permission to do that. And if they did it without negotiating or getting permission, we, the union, can pursue that through an arbitration. There will be circumstances in which she could sue them in court if she wanted to. So there are legal remedies that are already built into the collective bargaining agreement to address any kind of use beyond the original use. And that includes making it part of an AI training data set, that includes use of clips, it includes any aspect of that kind of use."

While there are safeguards in place against major studios engaging in bad behavior, those don't apply to the comparative Wild West of deepfakes. But SAG-AFTRA is trying to protect its members from that, as well. Crabtree-Ireland explained that the union has had success in getting some legislation enacted in New York and California to help put those protections in place, but he would still like to see action taken at the federal and even global levels.

That's all well and good for union members. But what about people who aren't union members? In addition to downloading NAVA's free AI rider and applying that to their contracts, is there anything that can be done for them? Crabtree-Ireland said even non-union work can be done under union contracts that help protect people from being exploited.

"It is really hard to envision how you can adequately protect people from this sort of thing without using collective bargaining, because there is such a tendency for overreach on the part of companies who do this stuff. And if you aren't part of a collective bargaining group and you don't have a lot of leverage, it can be very hard to push back on demands that you do things like sign away your rights to your image, likeness, or voice. What I would just say to everyone who will be reading this is it is essential that you not do that. Once you've signed away, in perpetuity, the rights to your image, likeness, or voice, it is virtually impossible to get it back. We've seen many, many examples of people that have really been abused in this way. I know it's really hard to say no to that sort of thing, but it is essential that you say no to that thing. One way you can do that is simply by reaching out to us to help get a project organized. Even if you're not a member yet, we can help organize projects. And once they're under a collective bargaining agreement, now it's no longer the individual performer's job to have to fight that."

It's also worth noting SAG-AFTRA is working with other partners inside and outside the industry to, as Crabtree-Ireland put it, "establish a common set of principles for the human-centered implementation of AI technology."

"This goes beyond voiceover or even beyond just the entertainment industry," he says. "This is a broader issue."

If the past few months are any indication, artificial intelligence is going to be a major part of our lives going forward. That may be an uneasy realization for many, but Abigail Savage suggests we shouldn't be afraid of it.

"I think right now, people are uncomfortable with it unless it's very [clearly] specified in a project, 'This is an AI-recreated voice of this past person. They never really said these lines into a recording.' I think if the common audience knew the degree to which we are already manipulating reality when we are doing sound editing work, I think it would be less controversial. At some point in the future, it's probably going to be more normalized, because we're already cobbling together interviews to make people say sentences that were never actually spoken. I do documentaries all the time, and the degree to which we are imposing, manufacturing, a reality so that the director's viewpoint and the interviewee's viewpoint comes across in a more obvious or clear manner, I think would really shock most audiences ... At some point it will, I think, become a normal tool in our toolkit for being able to tell stories."

"CGI sucked when it first came out too, but it was abused everywhere," she concludes. "I think it took something away from filmmaking for a few years while we grappled with how much to use, how to use it, and the fact that there was a deep uncanny valley going on. Technology gets absorbed by artistry, and artistry eventually wins out."