How Vince Gilligan And Breaking Bad's Writers Cooked Up A Perfect Final Season [Exclusive Interview]

September 29, 2013. On that Sunday, when the clocks hit 9:00pm ET, over 10 million viewers planted themselves before their television sets, ready to watch a new "Breaking Bad" episode for the last time. One of them was this future writer.

That 10 million strong audience sat awed as story threads — some 62 episodes in the making — were finally tied up in "Felina." Walter White (Bryan Cranston) snatched a pyrrhic victory from the jaws of defeat and made a marginal penance by accepting responsibility for his sins. Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul) drove off to an uncertain freedom, ringing out with a primal howl after a series' worth of suffering.

The reviews were stellar, a flood of Emmys followed, and with "Felina" as the cherry on top to an already beloved season 5, the reputation of "Breaking Bad" as one of television's titans was secured. 10 years on from "Felina," Heisenberg is definitely a name that people remember.

How was this masterpiece of a final season created? Especially when "Breaking Bad" creator Vince Gilligan has made it clear there was never a grand plan, defying the myth that art must be planned as carefully as architecture or cuisine.

By speaking with Gilligan, interviewing several of his colleagues, and scouring for every glimpse behind the scenes possible, we're here to tell the story of how the fifth season of "Breaking Bad" was refined to crystal blue purity.

Note: These interviews have been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Getting to season 5

Even before season 4 had aired, Gilligan was fairly sure season 5 would be the end, telling The New York Times: "This was never intended to be an open-ended show. As creators of the show, we have to see it through to the end, to finish what we started."

When he said that, though, "Breaking Bad" season 5 was not assured. As Gilligan recounted to me, "Breaking Bad" answered to two powers that be: Its network, AMC, and its production company, Sony Pictures Television. How fitting, then, that season 4 of "Breaking Bad" was all about a conflict between business partners, one handling production and the other distribution. As the season aired, such a disagreement could have killed the golden goose. Per Gilligan:

"It was a very strange time for the show because the show was becoming more and more of a hit, but at the same time, the folks at AMC were making serious noises about ending the show because they didn't like the deal they had with Sony."

Negotiations dragged on into August 2011. While AMC wasn't dead set on killing the show, they wanted to be cost-effective; they put forth a (rejected) offer for a 6-8 episode season 5. Sony, meanwhile, pitched other networks about picking up the series. Eventually, after negotiation and consultation with Gilligan about his needs, the two sides agreed to a 16-episode final season.

The renewal of "Breaking Bad" was announced on August 14, 2011. Sony would have been happy with even more episodes (and more money), but Gilligan and his team had settled on 16, somewhat arbitrarily, as what they needed to wrap up the series: "We just pulled a number out of a hat, not literally, but figuratively," he said.

Gilligan stressed to me that the dialogue sounds "more adversarial" than it really was. Neither party was malicious or agenda-driven, but simply trying to balance their own business needs with that of the show:

"Both companies, Sony and AMC, were always very solicitous toward me as the showrunner. They always said, 'Look, yeah, we want to make maximum. This is capitalism in action, got to make maximum hay while the sun is shining off this. But first order of business is we've got this very special show that people seem to like. What do you need?'"

True to their words, their season 5 agreement let "Breaking Bad" end on its own terms. Now that the writers' room had decided "how much runway" they were working with, they just had to figure out what would be landing on it.

The backdrop

With the show's future uncertain, the "Breaking Bad" writers and crew had made as spectacular a season 4 finale as possible. "Face Off," destined to air on October 9, 2011, saw Walter White finally triumph over Gus Fring (Giancarlo Esposito), clearing the greatest obstacle in his path as a confrontation almost three seasons in the making boiled over at last. Walt's declaration that "I won," turned from triumphant to horrifying with the revelation he poisoned Brock (Ian Posada), the son of Jesse's girlfriend, and framed Gus to rope in his old student. If Walt hadn't crossed the line into evil before, he sure had with this act.

So, now what?

That was one of the many questions that needed answering when on November 14, 2011, Gilligan and his writers reassembled: Sam Catlin, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, and Moira Walley-Beckett. Huddled inside their house of ideas, a second-floor suite of an ignominious office building in Burbank, California, they all felt "nothing but fear," Gilligan recalled.

They'd sacrificed their defining villain at the altar of the narrative climax, and in the process, had lost a magnetic performer in Esposito. Gus Fring helped "Breaking Bad" find its voice. Could it survive without him? Since the writers began season 5 with the knowledge that this would be the end, the pressure to land the plane and tie up every thread they could manage was strong. In a double-edged sword of stress, "Breaking Bad" was now more popular than ever before, with even more fans to risk disappointing.

Netflix binge-watchers made "Breaking Bad" into a sleeper hit just in time for season 5 to take the world by storm. Look at the ratings. Before season 5, the only time the show had cracked two million viewers on first airing was the season 4 premiere, "Box Cutter." Season 5A passed that benchmark every episode — the lowest rated, "Hazard Pay," came in at 2.20 million — and then the Season 5B premiere, "Blood Money," doubled that with 5.92 million viewers. "Felina" would in turn nearly double that figure.

Gilligan is grateful to Netflix, calling them the "third leg of the tripod" of the series' success between AMC and Sony. That said, he feels it was ultimately serendipitous:

"I think 'Breaking Bad' could have been the same show it was, but it might not have become what it became if the timing had been six months earlier or six months later. It's just that was where the dumb luck comes into play."

Increased interest in the show meant tighter security; only Gilligan himself was allowed to take home (watermarked) copies of episodes. To watch the episodes free of that blemish, editor Kelley Dixon had to use a "seven-inch wide" screen in producer Melissa Bernstein's office before the copies were sealed back in a safe.

Luckily, the show's casting directors, Sharon Bialy and Sherry Thomas, already had a plan in place to prevent leaks from auditioning actors. Actors who sent in audition tapes from home would receive scripts that had been watermarked with their names and heavily rewritten by writers' assistant Gordon Smith to remove the context of "Breaking Bad," let alone any spoilers. Jesse Plemons, when auditioning for Todd Alquist, was given a scene of a soldier being questioned about gunning down hostiles (this can be seen as a special feature on the season 5A DVD set). Apparently, Laura Fraser (who joined the series as Lydia Rodarte-Quayle this season) was so impressed by her fake audition scene that she was baffled that it wasn't the real thing.

As for those real scenes, the writers' room banged their heads away trying to write them in a way that did the series justice. In Gilligan's words, "It was all of us sitting in a room saying, 'What do we have left to do? Well, what's the biggest single thing we have left?'"

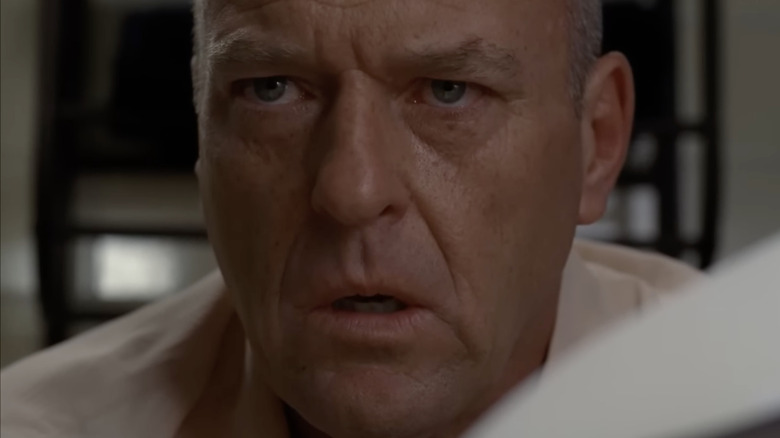

For the writers, that biggest hanging thread was Walt's DEA agent brother-in-law, Hank Schrader (Dean Norris), discovering the truth. "We'd be leaving untold drama on the table if we had Hank never figure out that his brother-in-law was Heisenberg," Gilligan said. "We can't do that. We can't do that to the audience. That'd be terrible." As George Mastras told me, a blow-up between Walt and Jesse was also inevitable. So began the work of patiently building to these climaxes.

Breaking the season

A common rule in fiction writing is to put character first. But what does that actually mean? For the "Breaking Bad" writers' room, it came down to one question they asked over and over: "Where is a character's head at?" Then, they let the answers guide the story.

As for Walt's head, it had a new crown atop it. Mastras recalls Gilligan telling him, "There's no story left. He's already gotten to the empire. What is there left?" Instead, the writers turned what seemed like an endpoint into a new beginning. The first half of season 5 offered Walt a taste of victory — Gilligan's pitch for "Breaking Bad" was famously to turn Mr. Chips into Scarface, so now the writers got to play around with that fully realized transformation.

"We wanted Walt to be the king for a while in that first stretch," said Gilligan. "He's beaten all of his enemies and he's beaten the biggest baddie of all, Gustavo Fring, so what does he have left to prove?"

As it turns out, running a meth empire comes with challenges and logistics. "I always have the position that, well, it's interesting he's won, but there's problems of trying to run the empire," recounted Mastras. "He's never run an empire. How does he do it? And so it became the issue of how do you run this? How do you hold it together?"

Without Gus' infrastructure, Mastras noted, Walt would need his own source of supplies. This question, of where Walt would get the methylamine to cook more of his "Blue Sky" meth, ultimately led the writers to the train heist realized in Mastras' "Dead Freight" (more on that to come).

As for cooking the meth, Walt no longer had Fring's hidden super lab, but the writers had already conceived of their solution. Whenever the writers first met to plot out a "Breaking Bad" season, they had four tools: A cork board, push pins, magic markers, and index cards. The writers pitched "big ideas" that they might want to use during the season, then wrote them on the cards and pinned them to the board so they were always close by while writing. The details of making these ideas work actually came later, said Gilligan on the "Breaking Bad Insider" podcast, "but we try to think ahead as far as possible."

One of Gilligan's first big ideas when developing season 5 was for Walt and co. to cook meth inside tented houses being fumigated. After struggling to make this enamoring idea "credible," Peter Gould recounted on that same podcast that they decided upon criminals/burglars moonlighting as exterminators as part of an existing scam. Enter Todd and Vamonos Pest in Gould's scripted episode, "Hazard Pay."

Most of the indexed big ideas wound up unused. However, Gould managed to work one of his own into "Hazard Pay": Mike Ehrmantraut's (Jonathan Banks) warning to Walt, "Just because you shot Jesse James, don't make you Jesse James."

A collaborative writers' room

Vince Gilligan is a big believer in collaborative writing. He once said, "The worst thing the French ever gave us is the auteur theory," and doesn't think that theory should be transposed onto television: "There's a perfectly good medium for directors, and it's called film. TV is a writer's medium. I am chauvinistic toward writing because that's where I came from."

Read or listen to any interview with Gilligan, and he always raves about his writers, actors, and crew; in my research, the feeling is definitely mutual. When I mentioned this "nice guy showrunner" reputation to Gilligan, he assured me that he's "cognizant" of how he can be perceived and that he's not all "aw shucks." For Gilligan, teamwork isn't just about being gracious:

"I'm not the nicest guy in the world, and a lot of that team effort stuff is not about being nice or selfless, it's about getting the best work. It's about having your name, when your name is on something, about it being the best it could be. And everybody does this job differently and there's some folks who do this job who write every episode themselves, who direct every episode. I don't even know how it's humanly possible, but more power to them. But that's not how I get my best work done. I surround myself with smarter people and people who can work harder than I can at this point, and I and my producers get the best we can out of them. And that's a very selfish thing to me."

Selfishly or not, Gilligan fostered an environment where everyone's ideas were heard, not only his own. While he'd long lost sympathy for Walt, he stayed silent about that distaste around Bryan Cranston — he didn't want his own perception of the character to affect Cranston's performance.

The writers' room had a "there are no dumb questions" policy. When devising their story, they worked through every permutation, and the only way to make that work was if everyone felt like they could put forth any idea without blowback. "You've got to start with the bad ideas to get to the good ideas," as Gilligan put it. "If you're really nervous about saying something dumb so that everyone around you was like, 'Oh, that was stupid,' then you are going to have long stretches of silence." Plus, if you work through every possible decision your characters can make as a habit, then pinning down the right choice for them becomes easier in the long run.

Big ideas weren't the only shared responsibility. The nitty gritty work in the "Breaking Bad" writers' room was "breaking" episodes — laying out the story of each episode, beat for beat, divided up into five acts (a teaser and then Acts 1 to 4, divided by commercial breaks). This ensures a strict outline for the eventual scriptwriter and a cohesive season, episode by episode. Their best friend in this process was, again, the index card. Episode beats would be written on these cards with magic markers and then pinned, in sequential order, to cork boards in the writers' room.

Me & my Board. The cards for the episode I was about to outline then write: #OZYMANDIAS. #BreakingBad @TorScreenConf pic.twitter.com/xjJ7Ldx6qL

— Moira Walley-Beckett (@YoWalleyB) April 30, 2016

Gilligan had learned this process while working on "The X-Files" and carried it over now that he was running his own writers' room. Even the writers themselves often can't pin down who first pitched which ideas, while episode assignments were very much luck of the draw. As Mastras recounted to IndieWire: "For the most part, it's so thoroughly broken in the room that anybody could really write [any] script."

That's not to say that each writer didn't have or know their own strengths. Mastras (who'd been with the show since season 1) considered himself one of the show's action/set piece experts, going back to his debut "Crazy Handful of Nothin'" (when Walt blows up kingpin Tuco Salamanca's den with fulminated mercury). That experience came in handy for his job this season.

Writers become directors

"Breaking Bad" season 5 began shooting on March 26, 2012. The writers' room and post-production facilities may have been states away from ABQ, but the writers weren't strangers on set. They were on-site when their own episodes were shot and could even help guide them to completion. When shooting the season's fourth episode, "Fifty-One," Sam Catlin helped director Rian Johnson change the blocking in a confrontation between Walt and Skyler (Anna Gunn). Rather than Walt slowly approaching a "stationary" Skyler, the scene became a cat-and-mouse game of Walt constantly cornering Skyler, reflecting how she feels utterly trapped.

It wasn't just the set visits that helped the writers think visually, but their own work, too. Thanks to their beat-by-beat breaking process and Gilligan's own experience directing, the writers' room would hammer down a scene's visuals as much as its narrative functions. "Breaking Bad" didn't look cinematic just because it was shot on 35mm film.

Mastras said the show's writers' room was more visually oriented than others he's worked in:

"What's the opening vision going into a scene? What is it coming out? These were things that we discussed in the writers' room. And it doesn't happen in most television writers' rooms — in my experience, anyway. So that made you start just thinking much more visually as opposed to [...] the playwright version."

For season 5, this visual practice paid off when three longtime writers became directors; Catlin was one of them (with 5B's "Rabid Dog"), as were Mastras ("Dead Freight") and Schnauz ("Say My Name"). Mastras recalled his gradually building interest in directing, while Schnauz said he got the itch back in season 4 — there wasn't room on the docket for him then, but there was in season 5.

Mastras got the most technically challenging episode: the fifth season's fifth episode, "Dead Freight," in which Walt and co. rob a freight train carrying methylamine. The simple solution to Mastras' question of supplies? The characters steal it. Since "Breaking Bad" is a neo-western, a train robbery was the obvious next step. Going back to 1903's "The Great Train Robbery," few images are more synonymous with frontier cinema than outlaws robbing a train.

The writers and their characters now faced the same question: How would they pull this robbery off?

Hauling Dead Freight

Before settling on the train, the writers considered other methods of robbery. One of their more pie-in-the-sky ideas was to have Walt and co. rent a helicopter to raid a railyard, sucking up the methylamine in a freight car with a long hose. Gilligan actually asked executive producer Michelle MacLaren to run this idea through logistics; she consulted with pilot Steve Stafford before they dropped this idea.

For a while, a trailer truck robbery was the most seriously considered option. Then, it was discovered that this option wouldn't be that much cheaper than staging a train robbery. So, to Mastras' delight, the team decided they might as well be ambitious.

The train line used was the Santa Fe Southern Railway; the train itself was the railway's own SFR 07 locomotive, and the filming location was halfway between Santa Fe and Lamy. Part of this same stretch of land had been used to film a train robbery sequence in "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid," so the "Breaking Bad" crew was treading the path of past filmmakers.

Shooting a "Breaking Bad" episode usually took seven to eight days, but this one was scheduled for 10 and a half, with four days blocked out for the train sequence. As shooting grew nearer, Mastras' fear grew alongside his palpable excitement. He told me that he scouted the shooting location well ahead of time to familiarize himself, allowing him to envision how he'd film the area and incorporate those ideas into his script.

Mastras rose to the occasion, but he also had a dream team of support. Gilligan himself was present for all four days of the train shoot. Michael Slovis, the show's usual cinematographer (and occasional director), was the DP. Nina Jack, a first AD (assistant director) since season 3, again filled that role.

MacLaren, one of the show's most prolific and dynamic directors (she'd helmed the Mastras-scripted "IFT" and "Thirty-Eight Snub"), shot the second-unit footage of "Dead Freight." For shots of Mike looking at the train from a distance, MacLaren's team used a long lens to emulate the view of his binoculars. This meant two views of the same events could be shot simultaneously by both units.

As for the main unit, they needed the maximum amount of possible coverage of the train itself. That meant stationing different camera teams around the track and using everything from cranes for high-angle shots to DSLR cameras mounted across the train for extreme close-up POVs. A camera mounted on a Gobo arm by Gilligan was knocked off the train by a brush branch when the train started to move (yet miraculously, still functioned afterward).

Gilligan admitted that robbing a moving train was beyond the crew's capability, so the writers had invented a reason for the train to stop (Bill Burr's henchman character, Patrick Kuby, parking a truck on the track), which turned an impossible job into a challenging one.

Practicality and safety were still paramount, especially when filming with a moving train. Communication was also complicated by the train being eight hundred feet long (crews stationed at one end wouldn't notice ones at the other) and that the filming spot actually was in dark territory, a telecom blackout zone name-dropped in the episode. Gilligan may have lost some sleep over safety concerns, but the extra care meant the crew all safely walked away.

Logistical concerns with moving the camera crews around the train are also why it was shot out of sequence; it was miles more efficient to shoot all the shots set at a particular spot in one go than constantly moving camera crews back and forth. Editor Skip MacDonald was left to organize the footage. Editing is where the episodes' only computer enhancements come in, such as rotoscoping to make the train look faster than it really was.

Aaron Paul also wasn't actually under the train when it moved over Jesse on the tracks — the camera crew had a crane shot looking straight down at the tracks. They filmed a shot of Jesse lying still and a shot of the train moving. The shots were digitally merged in post-production, emulating the old camera trick of a double exposure (locking a camera, running the film, rewinding it, and then running it again so that two images are imprinted on the film and look like one).

While filming was a triumph for the crew, Mastras had felt that it couldn't be a total victory for our thieves themselves. Hence the infamous ending, when Todd shoots a young boy named Drew Sharp (Samuel Webb) who witnessed the robbery. Todd had previously been conceived of as a "quiet crazy guy," and this moment was the writers' first organic opportunity to show that. After breaking the episode, they looped back around to the beginning and planted the seed for this shock ending with a teaser introducing Sharp. Mastras recounted to me:

"The shooting of Drew Sharp was something that I really advocated for, because for me, I didn't just want to do a successful heist. I feel like there always used to be consequences to the crime to bring it back to reality."

Mastras, as a former criminal investigator and youth counselor, brought particular awareness to the writers' room of how crime hurts children.

Alienating allies

The death of Drew Sharp was a lynchpin moment in plotting the rest of season 5 and the crucial breaking point in the most important relationship of the show: Jesse and Mr. White.

Mastras said on the "Breaking Bad Insider" episode covering "Dead Freight" that the murder was meant to hit Jesse especially hard, being "the worst thing that could happen" because he loves kids. In imagining where Jesse's head was after that, the writers wound up uprooting their plans. "We had all these ideas of Walt's going to retire, and Jesse's going to be the big meth guy in Albuquerque," Thomas Schnauz told me. "And once the kid got shot, that all got wiped off the table." He elaborated:

"When we write, we flowchart a lot. And we say, 'What if this happened? What if that happens?' And one of the logical things is that Jesse is in the meth business and he's proud of what he does and he's good at it, and they're making the big bucks. And so the logical thing would be that Jesse would continue and Walt would get too sick to continue or pull away and let Jesse take over the operation."

Instead, it was the opposite; Jesse spends the rest of 5A trying to get out of the business and Walt tries to reel him back into the empire. Schnauz explained:

"Walt, [unlike Jesse], can compartmentalize. They've done so many terrible things [...] So many things that he's pressed down that he tries to convince Jesse that yes, it was a horrible, terrible thing, but be strong and move on, and come with me on the successful journey that we're on because Mike's leaving so Walt doesn't want to be on his own."

That brings us to the other defining tragedy of season 5A: The death of Mike, murdered by Walt in a pique after laying down his frustrations and some hard truths in "Say My Name." The writers I spoke to couldn't pin down exactly when the decision to kill Mike came, but described it as an inevitability in the flowchart they'd drafted.

Gilligan explained that when they began writing the season, they knew Mike would have to be a thorn in Walt's side:

"We wanted to keep the character of Mike Ehrmantraut active in the show because we love that character. We love the guy who plays him, Jonathan Banks, but he had very much hitched his wagon to Gus Fring, and so we knew God, he's going to come, he's going to murder Walter White the minute he lays eyes on him after this thing happens."

Hence, the writers forced Mike and Walt to work together when Mike's employees from Fring's operation were arrested — Mike needed income from the meth business to make up for their seized pay. Mastras offered his knowledge of racketeering cases for this storyline: "One defendant can say something and it incriminates everyone." Walt, who again compartmentalizes violence, just wants to silence Mike's guys. Schnauz said this conflict meant Mike's story had to end the way it did.

"I think we knew [Mike had to die] because he was just too smart [...] Just like us writing if we were going to have Walt kill Mike's guys, Mike wasn't going to stand for it. So Mike had to be gone and not just out of town because he'd hear about it and come back. So yeah, collectively as a group, we came up with how it happened down by the river."

Gilligan ultimately broke the news of Mike's imminent demise to Banks while they were at Aaron Paul's engagement party. Banks, though, was unphased, telling The Wrap: "I honestly always thought I was gonna die. The bad guy's gotta die. It didn't come as any surprise at all."

One person who was surprised was Cranston, who found himself finally unable to reconcile with one of Walt's crimes. Moira Walley-Beckett recounted at a 2018 "Breaking Bad" writers' reunion:

"Bryan, the man who was the character of Walt and had been protecting the character fastidiously, repeating the lie of the character in order to play the character, and he was in a moral crisis as a person and an actor and the man who played Walter White when he killed Mike. And I watched Bryan go through that where he couldn't protect the character anymore and he had to start accepting the darkness within and it was very hard for him."

Walt was about to get a wake-up call of his own.

The money pit

"Gliding Over All" (written by Walley-Beckett, directed by MacLaren) features Walt on top of the world, or at least as close as he ever gets. He loses Jesse but solidifies his empire with new distribution, courtesy of Lydia and fellow meth kingpin Declan (Louis Ferreira), and gets a replacement apprentice in Todd. Two montage sequences spell out his reign. The first shows him orchestrating the murder of Mike's imprisoned men, carried out by Aryan Brotherhood comrades of Todd's Uncle Jack (Michael Bowen).

This scene was shot in a shuttered prison in downtown Albuquerque, described by Walley-Beckett on the "Insider" podcast covering "Gliding Over All" as "one of the most heinous places I've ever been in my life," and recalling that it smelled of "death and feet." Writing the episode, she was vague in describing the deaths, imagining them as "simpler" and "imagistic." But when MacLaren got the assignment of directing, "she really wanted to see some active murders." So the murders became full-fledged stunts, requiring more prep time. The final murder, when one of the men is locked in his cell and burned alive? While shooting that, Walley-Beckett felt "the palpitations of being responsible for somebody's life."

A second montage, set to Tommy James and the Shondells' "Crystal Blue Persuasion," shows the inner mechanics of Heisenberg's operation. Skyler eventually takes Walt to the storage unit housing his pile of drug money; the stack reaches up past their knees and stretches as wide as any of the corpses Walt has put in the ground. The sight alone hammers in Skyler's question: "How much is enough?"

For Gilligan, this was the logical endpoint of Walt's time as the king. Heisenberg had to ask himself the same question the writers had at the outset: After he's won, what then? That they tied it together with the season's other running thread, Skyler's disgust with what her husband has become, made it all the more organic.

As for creating the pile, it was "one of the toughest props our prop department ever had to put together," Gilligan recounted. It was composed of fake money rented from a California prop house, with a box hidden underneath to make it look even larger. Once shooting was over, the prop department had to go through the pile and account for every single bill.

While Skyler "has no earthly idea" of the amount, Gilligan had prop master Mark Hansen estimate it; his $80 million figure was eventually quoted in the series. Regardless, the sight of the pile and Skyler's cutting questions get Walt to quit. Gilligan told me the closing moments of "Gliding Over All" are meant to fool the audience into thinking it is "some kind of happy ending." Until the very last scene, in which Hank discovers Walt is Heisenberg.

Walley-Beckett drew on her season 4 episode, "Bullet Points," where Walt and Hank observe a copy of "Leaves of Grass" belonging to late meth cook Gale Boetticher (David Costabile) and addressed to "W.W." Hank finds another copy of "Leaves of Grass" addressed to Gale's other favorite W.W. in the White family bathroom. The episode cuts in flashbacks to that moment to underscore itself; for Gilligan, that exposition was worth it just to hear Bryan Cranston's faux-innocent, hands-up delivery of "You got me" one more time.

This ending of "Gliding Over All" shows how the strength of the "Breaking Bad" writers' room was building on the past. As Peter Gould recounted to Vulture:

"One of the things that Vince really instilled in us was to, instead of constantly introducing new things, look back at all the elements that we already have on the shelf. What can we mine from the things that we've already established? It's one of the things that helps the show have a feeling of unity."

This is why "Breaking Bad" hangs together despite there being no master plan. This skill at weaving old threads was especially useful now that the chickens were coming home to roost.

Splitting the season

The stress of crafting the final season meant the writers' room, according to Gilligan, were wasting less time than usual, but also taking longer in their work. Breaking episodes was taking three weeks each, not the usual two. In the interest of getting the opening episodes on air in time and in top shape, the writers decided to split the season, leaving them more time to plot the home stretch.

The mid-season break was decided upon and was confirmed to the public in April 2012. Gilligan said that AMC, in its quest for fewer episodes and higher profits, liked the "two eight-episode half-seasons" structure.

Both the writers and production crew took breaks. Shooting for 5A wrapped in the summer of 2012, while the writers' room hiatus began in June 2012 as well. This freed up the creative team's schedules; Gilligan got to spend more time in the editing room with Dixon and MacDonald, which he wouldn't have been able to do if he'd had to focus only on writing. In July 2012, several of the "Breaking Bad" cast, writers, and producers took their first journey to San Diego Comic-Con, with the packed convention hall serving as an up-close reminder of how popular the show had become.

The writers' room was officially reassembled later in the summer of 2012, but beforehand, Gilligan, Gould, and Schnauz had preliminary idea meetings. One of the pitches that came out of those meetings, per Schnauz, was a scene where, "Jesse kills Hank while Walt watches through binoculars while talking to Jesse on the phone." This was obviously discarded, but it reflects the unresolved stories weighing on them at the time.

Where the wind blows

When the room resumed, the writers once more worked through every outcome and its consequences. In doing so, they kept no character death off the table. Peter Gould confirmed to Entertainment Weekly that even though a spin-off about lawyer Saul Goodman (Bob Odenkirk) was already on their minds, Saul was no safer than anyone else. In the end, though, they decided that it fit for Saul to be "the cockroach that survives the atomic apocalypse." If they'd taken another path, we might never have met Jimmy McGill, the man behind the mask.

As for the elephant they'd left in the bathroom, how would Hank react to his discovery? Would he immediately confront Walt with their family in view? Would he let it go? The last one they quickly decided against — it would be out of character and dramatically unsatisfying — but they had to walk through everything, especially as they plotted out Hank and Walt's climactic chess match.

One thing the writers quickly switched gears on, though, was Walt's cancer. When Walt visits his doctor in "Gliding Over All," the scene, as scripted, was him being told his cancer is still in remission. However, the finished episode was more ambiguous. This left the writers with the room to change plans, so the mid-season premiere "Blood Money" revealed Walt was back in chemotherapy. This totally recontextualized the previous episode, added urgency to Walt's decisions, and brought the series full circle.

Walt's resurgent cancer led them to one of the most important pieces on the table: Skyler. Would she take her husband's side or her brother-in-law's? Gilligan recounted that this was "one of the hardest decisions" the writers' room ever faced, but they settled on the former. In Schnauz's words, "sometimes you just have to go with the more dramatic decision." But that doesn't mean they forewent the cardinal question of, "Where is this character's head at?"

As Sam Catlin told Vulture, the writers ultimately decided that "the fallacy of sunk costs" would drive Skyler this season; she'd fallen too far into Walt's corruption to back out. Anna Gunn analyzed her character on the "Insider" podcast episode covering "Buried," saying: "The cancer is both awful for [Skyler] but relieving [...] She feels that instead of giving it over and going through that s***storm, as it were, why don't we just let time take care of it?'"

Hank wouldn't be totally alone in his quest, though.

Breaking goes overboard

After "Dead Freight," the writers knew Walt and Jesse wouldn't end the series as friends. As Mastras recounted to me, "[Drew Sharp's death] really turned into the catalyst for the end really, spinning, turning Jesse against Walt. And that gave us that tool, I think unknowingly at the time, to really have that be the central conflict between the two characters that led to the overall ending."

While this murder had pushed Jesse away from Walt, they still weren't quite enemies. With the writers' mindset of building on the past, they had plenty of options to light that fuse. Would Jesse discover that Walt had killed Mike? That he let Jesse's girlfriend Jane (Krysten Ritter) die all the way back in season 2? Or would he finally learn the truth about Brock?

Gennifer Hutchison (who got the honor of penning the revelation in 5.11, "Confessions") said to Vulture that the writers weighed which revelation was the worst before deciding on the latter:

"Brock was always something we wanted Jesse to find out. That was something we'd been talking about since Walt poisoned him. It was just a matter of placing it. When is the worst possible time this could be realized? How about the time when Jesse is actually, maybe going to be okay? Let's do it then and ruin everything!"

Hence, Jesse and Hank, Walt's two new enemies, come together in 5.12, "Rabid Dog," to bring him down. That doesn't mean this was easy to write. Gilligan stated that this episode took over five weeks to break, and Catlin called it one of the "top three hardest episodes to break, ever."

In general, breaking season 5B was more time-consuming than the writers' room had anticipated. They had scheduled with the assumption they could break each episode in three weeks; instead, it was a month each. Gilligan had originally wanted to direct the last two episodes but thanks to his writing commitments, he only had time to helm the finale (Gould directed the penultimate episode, "Granite State," instead).

There was also one piece of the puzzle they couldn't fit.

Chekhov's machine gun

The first scene of season 5, way back in "Live Free or Die," featured a haggard-looking Walt purchasing an M60 machine gun on his 52nd birthday. The writers conceived of this without any clue of why Walt was buying the gun and without a final villain for it to kill. Answering that mystery was the most painful part of writing the season for Gilligan. As he told me, "There were times I was literally standing in the corner of the writers' room, slowly banging my head against the wall, trying to make the ideas loose and jar them loose and make them come out of my brain. And I think everybody was a little worried about my sanity at that point."

At times, a desperate Gilligan even suggested just forgetting about the machine gun, but his writers wouldn't let him, asking: "'Okay, but why? Because we did the thing with the machine gun and you have to pay it off.' It's the old Chekhov thing."

One of the ideas considered was that Walt would use the gun to free an imprisoned Jesse, but as the writers walked through this, they found this too distasteful an ending. Schnauz told me the writers asked themselves: "Do we want to see Walt break into a jail and shoot down a bunch of cops? Probably not."

Thankfully, they'd given themselves machine gun-worthy villains in 5A: Todd, Uncle Jack, and the rest of the Nazi gang. "Who doesn't love seeing a bunch of Nazis getting mowed down with a machine gun?" Gilligan rhetorically asked me.

Committing to the Nazis as the villains meant a bit of a board clearing, hence Declan and his crew's abrupt demise at Jack and company's hands in 5.10, "Buried." Schnauz, who wrote that episode, told me:

"Between Jack and his gang and Todd and then Declan and his group, it felt like there were too many, not loose ends, but just too many antagonists around [...] Actually we started coming up with Jack's gang getting rid of Declan's gang in the previous episode, 5.09, which became too packed full of stuff, and it shifted into 5.10, which happened to be the one I was writing. So I think Peter was originally excited about writing that scene, and then it got taken away from him."

As for how Walt uses the gun — the original plan was for him to simply wield it handheld. However, realizing that a sickly man could never pull off such an attack, they changed it to him improvising a garage door opener into a trunk-mounted auto-gun. Walter White was always more Angus MacGyver than John Rambo.

As usual, the "Breaking Bad" writers' room managed to weave a satisfying whole together from bits they'd established in previous episodes. That doesn't mean it was a fun process, though, and Gilligan left me with this warning about trapping yourself as a writer:

"We always endeavor to tell [the story] organically, but the most inorganic thing we ever did, and I take full responsibility for it, was this inorganic bit of business with the machine gun not knowing how that paid off. That is the essence of inorganic storytelling, and I learned a valuable lesson from that. Don't do that to yourself in the future."

Writing and directing a climax

Season 5B was ultimately pitched to AMC around October 2012, roughly eight weeks into writing. Shooting for "Breaking Bad" resumed in December as scheduled. The series' climax was a two-hand gut punch, 5.13 "To'hajiilee" and 5.14, "Ozymandias." Lured into a trap by Hank and Jesse, Walt calls on Jack's gang for backup, a mistake that destroys his empire and family forever.

The former was written by George Mastras and directed by Michelle MacLaren, the latter scripted by Moira Walley-Beckett and directed by Rian Johnson. These were honed writer-director pairs who'd worked together before, and that synchronicity created a well-fueled filmmaking machine.

Despite Mastras getting the directing bug for "Dead Freight," he was happy to let MacLaren take the reins for "To'hajiilee." "You always like to direct yourself, but I feel like on 'To'hajiilee,' she's also just this fantastic director and was known for being able to do these kick-ass [action scenes]." Mastras told me that he and MacLaren felt like "kids at a candy store" about all the setpieces, while Gilligan said of the episode, "I've got my action team on it."

Walt's frantic one-man car chase against time and an unseen Jesse was shot across four days in pieces and primarily on a green screen; the ideas of blocking off whole streets of downtown Albuquerque and having Cranston recite his lines while driving like a madman were both non-starters. Then, most of the desert shoot was spent on the quiet, dramatic moments of Walt surrendering to Hank. Between that and early sunsets costing them the light for shooting, there was only about a day to film the shoot-out between Hank & his partner Gomez (Steven Michael Quezada) against the Nazis. This had at one point been conceived as a "Heat"-esque spectacle (in Mastras' words, "Bodies dropping left and right"), but budgeting and time scaled it back. Even so, the "compromised" version still left viewers cursing a cut to black like nothing since "The Sopranos" finale.

Hank's death had been decided on well in advance. Dean Norris recounted to The Ringer, "Vince had told me two years prior, almost verbatim, what my last lines would be. So when I read [the script], I was like, 'There they are.'"

There was a back-and-forth about whether his murder would be the end of "To'hajiilee" or the beginning of "Ozymandias." The latter was chosen both to give the death breathing room and extra impact, rather than letting it get overshadowed by the shootout. Mastras was initially disappointed but saw the wisdom in the shift: "Instead of having it all play out on screen and having Hank kill a bunch of guys and everything, it actually turned out, suspense-wise, I think more satisfying to cut it out at that moment."

'Half sunk a shattered visage lies...'

Johnson had directed Walley-Beckett and Catlin's season 3 bottle episode, "Fly" and she requested him to direct her last episode this season. By chance, they lucked into the most important assignment. Both Gilligan and Walley-Beckett are poetry fans; the latter chose to title the episode "Ozymandias" after Percy Bysshe Shelley's sonnet about the time-ravaged legacy of the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II. She told The Ringer:

"When we started breaking the season, [the poem] flashed so powerfully in my mind as a theme for Walt, and Vince was super keen on that."

The episode's opening scenes, still in the New Mexico desert, came with extra complications. The sun was still setting around 4 p.m., which meant starting bright and early. Since they were picking up from a chaotic cliffhanger, Hank and Jack's cars all had be to carefully marked up with damage and photographed for continuity.

However, Johnson is a precise director; Gilligan admitted on the "Insider" episode about "Ozymandias" that while he tends to shoot more safety coverage, Johnson always knows what he wants with his camera. Rendering Walt's grief-fueled collapse with a dolly zoom was his idea, as was placing a "jig-saw" like contraption beneath the sand for Walt's head to land on. When he collapsed, dust rose like the ground was cracking beneath him.

The furiously grieving Walt sentences Jesse to what he thinks is execution, but turns out to be enslavement. The writers were conscious of letting Jesse off easily — his good heart couldn't shield him from consequences. Since this was their last chance to reveal the truth of Jane's death to Jesse, they took it and twisted the knife even further.

The rest of the episode remained emotionally taxing to shoot, particularly Walt and Skyler's carefully rehearsed confrontation. Skyler wielding a knife against her husband isn't a matter of simple practicality; Walley-Beckett told Entertainment Weekly that it is her trying to cut out the cancer in her family that Walt has grown into.

Not everything could be planned for, though. Some unexpected happenings impeded the episode (like a surprise hailstorm that briefly postponed shooting), but at least one benefitted it: The infant playing kidnapped baby Holly White "ad-libbed" a cry for her mother when Walt was staring at her. "That's one of those pure lightning strikes of luck that you probably don't get twice in a lifetime," Johnson said.

The last day of shooting "Ozymandias" was the final shoot of the whole series. The teaser, set during Walt and Jesse's first meth cook back in the pilot, meant Walt couldn't have his shaved head or goatee. Since Cranston grew back his hair for the last two episodes anyway, the crew decided to wait rather than go through complicated makeup procedures. The episode irrevocably ends the Whites' marriage, so Walley-Beckett wanted to open the episode by showing Walt's first lie to Skyler (that he's working late and can't come home yet). While most of the cast and crew felt bittersweet nostalgia (Gilligan himself got to call the final cut), Johnson admitted shooting the scene felt like "being at somebody else's wedding."

Deciding Walt's fate

As the end approached in the writers' room, they finally had to answer a question they'd been asking since November 2011: How would Walt's journey end?

Back in 5A, it was established in the opening teaser that Walt had fled to New Hampshire — Gilligan said to me that this choice was both due to his infatuation with the state's motto (the eponymous "Live Free or Die") and the cold environment, totally different from ABQ (even if they actually shot the New Hampshire scenes in New Mexico mountains).

The writers ultimately decided Walt had to die; Gilligan felt this was "implicit in the promise" of the first episode when Walt gets his terminal cancer diagnosis. But how would he go? Would it be ignominious? One option floated was Walt passing away on a hospital gurney; in Sam Catlin's words at the 2018 writers' reunion, Walt would be "pushed aside while life continued without him." It's hard to think of a more punishing fate for a man who wanted to leave a legacy, not spend his last days slipping away in a hospital.

The intertwined question was how much destruction Walt would wreak on his way out. One briefly floated idea was that everyone except Walt would die. A more seriously considered idea was Skyler fleeing with Walt and committing suicide. Melissa Bernstein recalls that as part of Gilligan's initial season 5B pitch to the network, but both her colleagues and his talked him out of it.

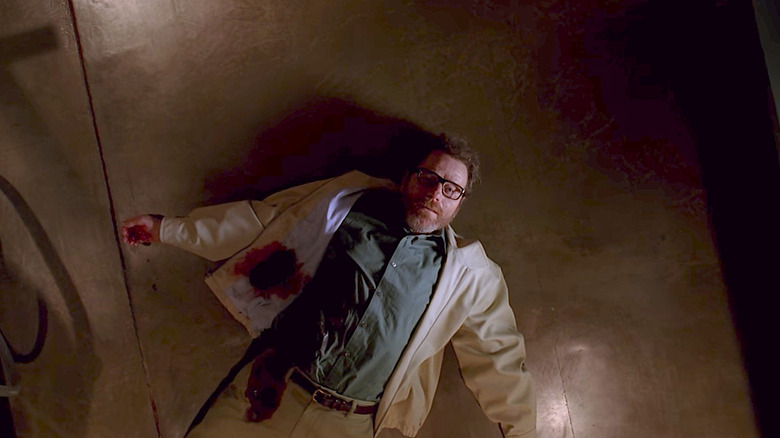

Mastras, an action writer to the end, was pushing for a big finale to Walt's character. He'd ask Gilligan, "Where's the showmanship?" To be sure, the ending does bank on letting the audience walk away satisfied. "Granite State" is Walt at his lowest, Gould describing it to Entertainment Weekly as Walt "hitting bottom," but the episode ultimately becomes about how he climbs out of that pit. He ends the show by killing his enemies, rescuing Jesse, leaving behind money for his children, and dying on his terms or, as Gilligan put it, "Like a man." One of the last lines of the "Felina" script? "He got away."

Walt couldn't fix everything though, especially not his own soul. Mastras told me that his self-designed last stand is in character for him and real-life criminals of his ilk, who sometimes choose to go out via suicide-by-cop. He added:

"I kept on talking about [a] blaze of glory, but I didn't see it as a blaze of glory. I see it as a tragedy. I see [Walt] as a modern-day Prometheus where he's bowing against the odds and it's going to have to end in tragedy. And I think the destruction of his family is the ultimate tragedy."

As Hutchison put it, "Walt's redemption is kind of dying" while also giving Jesse a chance to live as a better person. Not before he makes a penitent confession, though.

Gould said he and his fellow writers had decided that the end of the show had to be Walt accepting himself. "When is he going to really see himself kind of the way we did in the writers' room when we are our most judgmental?" Hence, Walt's admission to Skyler: "I did it for me." Gilligan has said that, just as a viewer, that line was something he wanted to hear "for a long time."

There even being a last scene with Walt and Skyler was about giving the fans "a proper goodbye" between the two characters. Still, Walt shows where his heart belongs by choosing to spend his last moments in a meth lab. It's his creation that he loved above all else. The cherry on top was the soundtrack.

Baby Blue

The policy on "Breaking Bad" was that scenes should work without music. Composer Dave Porter and the editors didn't even use temp music tracks. If you've seen the show, though, you probably know that music is part of its soul. On top of Porter's original score, a team led by music supervisor Thomas Golubić was in charge of sampling and licensing existing songs.

Despite his vast musical knowledge, Golubić saw his job as finding music that fit diegetically, whether with a character or setting. When he first got the job, he traveled to Albuquerque, perusing everything from restaurants and hardware stores to observe what kinds of music the people there listened to. In his recollection, ABQ music is "very out of time. It didn't feel contemporary or nostalgic."

However, Golubić's team had another member: Vince Gilligan's SiriusXM subscription. Gilligan remembers hearing "Baby Blue" by Badfinger while driving to work one day as the season was wrapping up. He was familiar with the song but absorbing it now felt uncanny:

"I'm listening to the words, because half the time I'm not really listening to the words, I'm just listening to the melody, and I'm listening to the words and I said, 'Holy s***. Oh my God, this would be perfect."

Golubić believes they'd floated using the song before; it was included on a sample mix tape they'd created of blue-themed songs, one that also featured "Crystal Blue Persuasion." He wasn't totally sold on Gilligan's suggestion of "Baby Blue," though, so he and his team went to work finding alternatives (with Gilligan's approval). None felt quite right, though, so Badfinger it was.

Despite the choice being relatively last-minute and the band's history (most of the members died young), there wasn't much issue with securing the rights to "Baby Blue." The publishing rights were cleared with Universal Music (via Amy Matusek) and the master rights with BMG Chrysalis (via Rob Christensen). The one tiny hurdle was that, for security/spoiler concerns, they couldn't disclose any information about the scene, beyond a promise it wouldn't be graphic. Golubić believes the rights holders didn't realize "Baby Blue" would be used as such a pivotal moment (nor predict the subsequent explosion in popularity after the episode aired): "I think in a sense they were like, 'Okay, well we'll clear that song [...] We're probably one of 50 different ideas."

As for Golubić, he remembers watching a "Felina" rough cut and finally understanding why Gilligan wanted a love song to close out the show.

"The truth is, of all the ideas that we'd thrown around, and some of them had blue titles, some of them were more thematic, some of them were more about his comeuppance, that was the scripted component to it. But honestly, I don't think any of them were better than ['Baby Blue']."

Kevin Cordasco

The "Breaking Bad" writers' room tried not to pay too much attention to what their viewers were saying in response to the show. Gilligan himself was unfamiliar with the hate for Skyler, having kept the forums where it festered out of sight, out of mind. However, one fan of the show got to leave his mark on it.

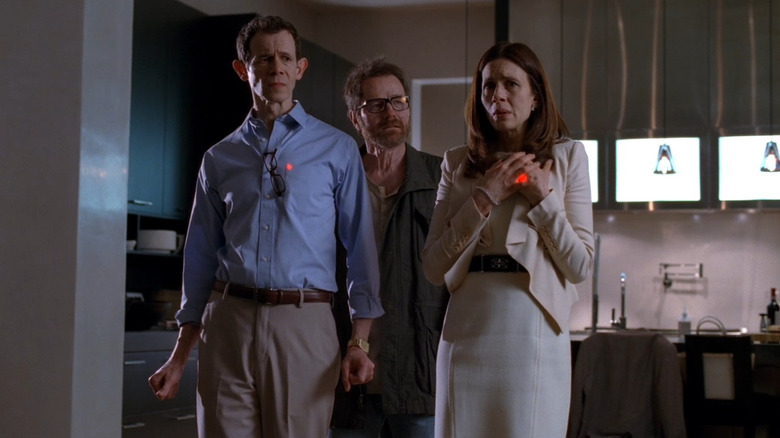

16-year-old Kevin Cordasco, a huge "Breaking Bad" fan, was fighting neuroblastoma as he watched the show. After a family friend arranged a visit from Bryan Cranston, Cordasco in turn met Anna Gunn, Bob Odenkirk, and the entire writers' room. Gilligan, impressed by Cordasco's passion for the show and aptitude for story structure, asked him what he wished to see on the show. His answer? He wanted to know more about Gretchen and Elliott Schwartz (Jessica Hecht and Adam Godley), Walt's old college friends/business partners turned billionaire pharmaceutical moguls.

Sadly, Cordasco passed away on March 11, 2013, five months before season 5B premiered. ("Blood Money" was dedicated to his memory.) However, his request led not only to the reintroduction of the Schwartzes, but it solved two conundrums for the writers. First, how is Walt reinvigorated in time for "Felina"? He sees his old pals badmouthing him on TV. After all, it's implied throughout the show that the roots of Walt's inferiority complex go back to the mistake he made in backing out of their soon-to-be-successful company. Second, how would Walt bequeath his remaining millions to his kids? Simple: He blackmails the wealthy Schwartzes into laundering it as a "donation" to them.

Cordasco's memory lives on, in part, as a component of the legacy of his favorite show.

Helping to build the Brooklyn Bridge

Shortly after the series concluded, Gilligan quoted his old "X-Files" director/producer pal Rob Bowman about the journey: "The pain fades but the glory remains." To be sure, the glory was soon to come at the 66th Primetime Emmys. "Breaking Bad" swept almost all the dramatic categories, and it was even competing with itself in the Outstanding Writing for a Drama Series category. For the record, Moira Walley-Beckett won for "Ozymandias" over Gilligan for "Felina." If anyone was clapping harder than him, I'd be surprised, and when Walley-Beckett claimed her prize, she declared, "Vince Gilligan, this is your fault!"

When I asked Gilligan if he wished he'd been more personally involved in any episodes, he said no. He's satisfied with thinking of himself as just one part of a team effort, breaking it down like this:

"If you were there from the beginning all the way through to the end building the Brooklyn Bridge, yeah, I would imagine the folks who built that bridge, for the rest of their lives, they would take their grandkids to see it and say, 'I had a hand in building that thing.'"

It wasn't long before Gilligan dove back into the world he created with "Better Call Saul" and "El Camino" — and many of his writers and actors went back with him. His feelings on "Breaking Bad" aren't all simple pride, though. Over time, he's grown less sympathetic to Walter White. He admitted at the 2018 writers' reunion that, "I, too, feel like Walter White gets a bit of a pass, more than I would personally give him."

He later told The New Yorker in 2022, "If [Walt] had been a better human being, he would've swallowed his pride and taken the opportunity to treat his cancer with the money his former friends offered him. He goes out on his own terms, but he leaves a trail of destruction behind him. I focus on that more than I used to." It sounds like the Vince Gilligan of today might not have written the same ending that his 2013 self did.

Netflix's success with "Breaking Bad" helped spur the company's entrance into TV production and the "binge-model," releasing whole seasons at once. Gilligan told me that he isn't in love with this change to his industry; the idea of dumping whole TV seasons on streaming platforms reminds him of the ending of "Raiders of the Lost Ark."

"I much prefer the old system where you have an episode a week for 13 weeks or 22 weeks [...] You unfold it gradually and it's not some weird race on a Friday night somewhere where people try to speed scan through 13 episodes so that they can tell everybody on social media how the thing ends."

While plenty of Netflix originals might be digitally buried like the Ark of the Covenant, "Breaking Bad" endures. Gilligan tells me that the show's cultural dominance can be both burdensome and comforting, precisely because he doesn't know if he can surpass it.

"When I get to worrying too much about that, I say to myself, 'Well s***, man. What are you complaining about? You had 'Breaking Bad.' That's what's going on. You already know what's going on your tombstone, so you should just relax and take the rest of it as gravy."

All seasons of "Breaking Bad" are available on Netflix.