The Unpopular Opinion: 'Interstellar' Is Christopher Nolan's Emotional Masterpiece

(Welcome to The Unpopular Opinion, a series where a writer goes to the defense of a much-maligned film or TV show, or sets their sights on something seemingly beloved by all. In this edition: a defense of Interstellar as one of Christopher Nolan's greatest movies.)

"If I can fix every detail of this time in my mind, I can keep this moment always." -Betty Smith, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

Christopher Nolan makes cold films. At least, that seems to be one of the biggest complaints frequently lobbied against the filmmaker. Film after film, from Memento to Insomnia to The Prestige to the Dark Knight trilogy and beyond, Nolan's work may be technically proficient and visually dazzling, but some audiences and critics alike come away wondering where the heart is. He's not a humanist filmmaker the way Steven Spielberg is, but more akin to Stanley Kubrick (before you crucify me for this statement, I'm only comparing Nolan and Kubrick on the emotional front, or lack thereof; this is not a comparison of their directorial abilities).Yet anyone looking for heart in a Nolan film need look no further than the expansive 2014 epic Interstellar, which may very well be his masterpiece. With Interstellar, Nolan intertwines the grand adventure of a space exploration film with a beating heart. "To me, space exploration represents the absolute extreme of what the human experience is," Nolan says. "It's all about trying, in some way, to define what our existence means in terms of the universe. For a filmmaker, the extraordinary nature of a few select individuals pushing the boundaries of where the human species has ever been or can possibly go opens up an infinite set of possibilities. I was excited by the prospect of making a film that would take the audience into that experience through the eyes of those first explorers moving outwards into the galaxy — indeed to a whole other galaxy. ... That's as big a journey as you can imagine trying to tell."

A Sense of Scale

Interstellar is big in every sense of the word. It journeys beyond our galaxy and further, through wormholes and black holes into entirely new worlds with waves the size of mountains and clouds that crystalize and shatter when struck like ice. Nolan creates huge set-pieces, complete with ticking clocks on Hans Zimmer's soundtrack that ratchet up the tension. That clock is always ticking somewhere in this film, whether we hear it or not, and with it comes the sense of impending doom, courtesy of big blockbuster filmmaking. You can practically see every dollar of the film's $165 million budget up on the screen.Yet in some ways, it's a small film as well. There are quiet moments, like when the main character watches video messages from his children beamed across the galaxy, or when Nolan cuts to a gorgeous wide shot of a spaceship seeming impossibly tiny as it drifts by Saturn, all while the soundtrack plays a soothing thunderstorm one of the crewmembers of the ship is listening to. And for all its spectacle and adventure, Interstellar is really a film about longing, about learning – about a father coming to terms with the mistakes he's made and striving to redeem himself."In broad terms, Interstellar is a spectacular adventure about a journey into the universe," says producer Emma Thomas, "but at its heart is an emotional story of a father and his children. It speaks to the love that exists in families, the notions of duty and sacrifice, and our profound connections to other human beings."

Bridging the Gap

Matthew McConaughey is Cooper, a former pilot quite literally grounded by the sorry state of the world. A new Dust Bowl has come about, destroying crops and devastating the population of the planet with it. The world strives to rebuild the future by altering the past. The textbooks at the school Cooper's daughter Murph (Mackenzie Foy) attends claim that the moon landing, and the American space program in general, was a bit of clever propaganda to bankrupt the Soviet Union. Through this misinformation, the powers that be strive to snuff out any dreams of exploration beyond this dying planet. "If we don't want a repeat of the excess and wastefulness of the 20th Century then we need to teach our kids about this planet, not tales of leaving it," says one of Murph's teachers.This logic is blasphemous to Coop, who is nostalgic for the days when man's reach exceeded his grasp. "We used to look up at the sky and wonder at our place in the stars," he says. "Now we just look down, and worry about our place in the dirt." Coop has had to become a farmer, because that's what's in demand right now, but all he wants to do is get away – to get back into the sky and beyond. He loves his children, Murph and son Tom (Timothée Chalamet), but he's also an absentee single parent, relying on the kids' grandfather Donald (John Lithgow) to take care of the middling details of child rearing.When Murph comes to Coop and claims there's a ghost haunting her room, Coop's first instinct is to shrug it off, but through prodding from Donald he takes a step back and tells his daughter that if she thinks there's a ghost in her room, she needs to approach it scientifically: study the phenomenon and try to come up with some sort of proof.In these early scenes on earth, Nolan sets up the true heart of the film: the relationship between Cooper and Murph, where Murph idolizes her father while Cooper seems to view her from a distance. That distance only grows wider, and wider, as the film progresses; it's a distance that stretches the length of the known universe. How do you bridge that gap?

Nolan's Most Emotional Moment

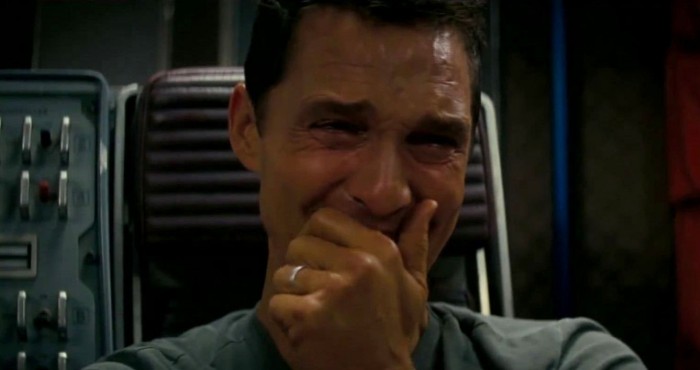

If it's proof of something supernatural Coop is looking for, he soon gets it. Books fall off shelves, and a the "ghost" spells a message out in the dust in Murph's room, leading Cooper and Murph to a top-secret research facility. There, Professor Brand (Michael Caine) heads a program with NASA with the daunting task of saving the world. A wormhole has suddenly appeared somewhere near Saturn, leading to another galaxy that may or may not have habitable planets.Volunteers have already traveled through that wormhole, sending back the possibility for sustainable life from at least three planets through the wormhole. The plan now is to send a new ship carrying human embryos to whichever planet is the most promising to ensure the survival of the human race, with Coop piloting the mission. Meanwhile, back on earth, Brand will work on finding a way of getting the current inhabitants of earth to safety.This results in the most emotional moment in Nolan's entire oeuvre, a scene that establishes the very backbone of the film. About to leave for the mission, Cooper attempts to comfort the understandably distraught Murph. She tearfully pleads with him, saying the ghost spelled out yet another message: S-T-A-Y, a clear sign that Cooper should stay. Nolan and cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema create a feeling of painful intimacy by bringing the camera in close on the characters' faces, cutting from Murph's tear-streaked cheeks to Cooper's pained expression. As far as spectacle goes, it's one of the most unspectacular moments in Nolan's blockbuster career, yet it has just as much impact as, if not more than, a large action-based set piece.

"Murph. You have to talk to me," Cooper pleads when his daughter tries to shut him out. "I have to fix this, before I go." "I'll keep it broken so you have to stay," she shoots back. Eventually, he finds a way to calm her. But when he lets slip the fact that he doesn't know when he's coming back, it's too much for Murph to handle. She has a breakdown and Cooper leaves her, sobbing. "I love you, forever," he tells her, which sure sounds a lot like "Goodbye, I may never see you again."

Fathers and Daughters

Steven Spielberg has spent his entire career crafting emotional blockbusters featuring abandoned children – children who pine for their absentee fathers, wondering just where they are and when they might come back. Interstellar finds Nolan tackling the inverse of this, telling the story from the point of view of the missing father. Interstellar does not excuse fathers who leave their children behind. Instead, this decision haunts Cooper for the rest of the film, as Nolan searches for empathy in abandonment. Cooper thinks he's doing the right thing, but the variables are too uncertain. For a man engrossed in science, he's betting a lot on blind faith: faith that the mission will succeed, faith that he'll return and see his daughter again.But Cooper is driven by more than faith: he's driven by love for his children. Love, an abstract emotion, not fully explainable and not easily quantifiable by scientific method, is also what powers Interstellar. Nolan went to great lengths to ensure the film was as scientifically accurate as possible, enlisting Caltech theoretical physicist Kip Thorne to serve as the film's scientific consultant. Yet for all this focus on accuracy, Nolan is willing to move beyond the scientific elements for the power of love."Love is the one thing we're capable of perceiving that transcends dimensions of time and space," says Coop's scientist crewmember Amelia (Anne Hathaway). This is the type of big, bold statement that can elicit a heavy dose of eye rolling from cynical viewers who approach their entertainment with a thick layer of irony. But Interstellar means this line in all sincerity.Near the film's conclusion, Cooper travels through a black hole only to end up within a tesseract that spans as far as the eye can see and is made up row after row of bookcases, looking in on Murph through various points of her life. It becomes clear that the "ghost" was Cooper all along, trapped behind these bookcases, desperately trying to send a message to his daughter. In a truly harrowing moment, Cooper (and the audience) are forced to rewatch the tearful goodbye scene again, as Coop hovers behind the bookcase shouting, "Don't let me leave, Murph!" to his daughter who cannot hear him.As hopeless and heartbreaking as this moment first seems, Coop realizes he can use it for good. He can, in a sense, attone for the mistakes he cannot change. He's able to reach across the vastness of the tesseract to find Murph at just the right moment, and convey to her a coded message to help save the people of earth. It's love that enables him to do this – that connection that transcends dimensions of time and space. It is quantifiable after all.

Reaching For the Stars

Nolan's films are often presented under a thin sheen of ice. There can, at times, be a frostiness to the films – an analytical distance like that of an indifferent deity passively observing the world he's created. Here, however, is also filmmaker who made a big, bold, expensive sci-fi epic that was ultimately about love saving the human race. "We've always had very emotional responses to the films, right back to Memento," Nolan tells The Hollywood Reporter. "[M]y work is very technical, very precise, possibly cold... [but] I think Interstellar is just more obviously personal and more obviously about emotion than my other films, so yes, it absolutely comes to the forefront, but it's because that's what the story is about entirely."The emotional resonance of Interstellar failed to connect with some. Perhaps, so used to Nolan's chillier films, viewers were caught off guard by how earnest this movie is. Yet any who still want to claim that the filmmaker only trafficks in cold and distant films are deliberately overlooking this beautiful, ambitious epic. With Interstellar, Nolan quite literally reached for the stars, and beyond, and created something genuinely emotional in the process.