The Twilight Zone's Rod Serling Gave Steven Spielberg His First Directing Gig

If you saw "The Fabelmans" — and judging from the film's underwhelming box office, you probably didn't — you might think you know exactly how Steven Spielberg broke into show business. Snap Wexley hired him to work on the hit TV sitcom "Hogan's Heroes," he got great advice from an ornery John Ford, and the rest was history.

Except Steven Spielberg didn't really work on "Hogan's Heroes," and he didn't get advice from John Ford when he was actually starting out in the industry. Instead, he met the legendary director of "How Green Was My Valley" and "The Searchers" when he was only 15 years old. It turns out that Steven Spielberg isn't really above smudging the truth a bit in his movies, if he thinks the truth gets in the way of a good story.

And like all good stories, "The Fabelmans" had to end somewhere. It didn't take "Sammy Fabelman" into his actual, professional directing career. If it did, it would have had to show Sammy on the set of the pilot episode for "Night Gallery," Rod Serling's successful horror anthology follow-up to "The Twilight Zone," which Spielberg directed when he was only 22 years old.

A 'Night Gallery' to remember

Spielberg's first official directing gig, after Universal Studios tasked him with making a short film called "Amblin'" in 1968 (that's where the name of his production company came from), was "Night Gallery." The pilot episode, originally released as a TV movie in 1969, was an anthology of three horror short films. Spielberg was one of three directors enlisted for the episode, along with Emmy nominee Boris Sagal ("The Omega Man") and Barry Shear ("Wild in the Streets"), each of whom tackled one the scary stories written by Rod Serling.

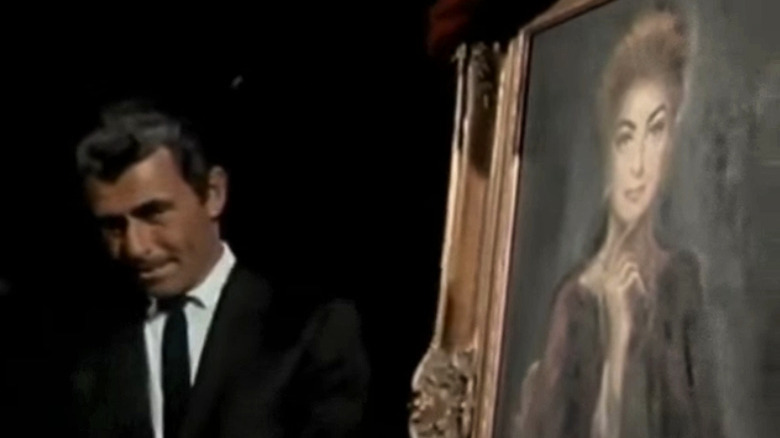

The premise of "Night Gallery" is that, in every episode, Serling introduces a mysterious painting that captures a single moment of terror. The episode then expands on that tale, revealing how the nightmare came to pass. The pilot features three tales of terror. The first, "The Cemetery," directed by Sagal, stars Roddy McDowall as a conniving, murderous nephew who gets tortured by a painting he inherits. The third, "Escape Route," directed by Shear, stars Richard Kiley (who would eventually provide the narration for the rides in Spielberg's "Jurassic Park") as a Nazi hiding in South America, who dreams of escaping into a peaceful painting, and receives instead an ironic comeuppance.

Spielberg's middle installment is the one best remembered today, and not just because its director became famous. "Eyes" stars Joan Crawford as a sadistic millionaire, blind since birth, who schemes to take the vision of a desperate man, played by Tom Bosley ("Happy Days"). The only problem is, she will only be able to see for a few hours, and as soon as her vision kicks in there's a massive blackout, and she doesn't get to enjoy it. It would rival "Time Enough at Last" for the most depressing ending in TV history if only she were the slightest bit sympathetic.

NBC's just not that into European new wave

Spielberg pulls out all the stops he can muster in "Night Gallery." Barry Shear's installment has the heaviest subject matter but lacks focus, and Boris Sagal's opener is a satisfying "Tales from the Crypt" type of story, atmospheric if somewhat conventional. But Spielberg drew the best straw when it came to the material, an instantly iconic tale of malevolent irony, with Joan Crawford giving the segment an impressive amount of energy. Tom Bosley is also beautifully tragic as the poor sap she manipulates into giving away his vision for a paltry $9,000.

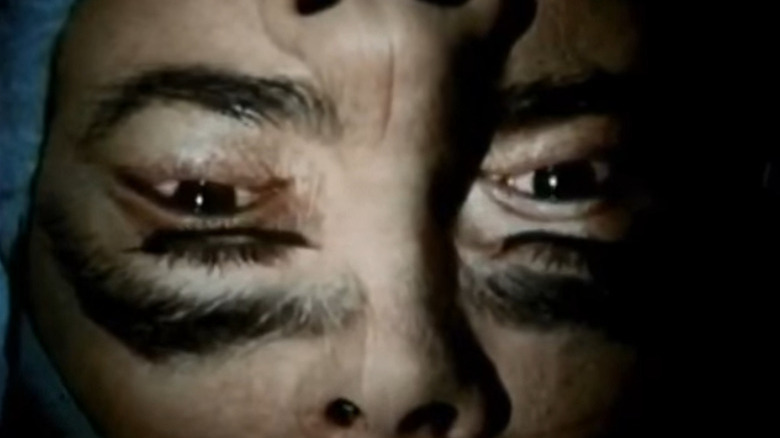

But Spielberg's attempts to goose the episode with showy cinematography backfired a little bit. Striking shots of Crawford's and Bosley's eyes merging, not unlike Ingmar Bergman's "Persona," tell the story beautifully. Others, like a mafia goon threatening Bosley on a spinning playground merry-go-round, don't tell the story of the episode so much as they tell the story of a young director trying to stand out whether it serves the story or not. And the segment's conclusion, which finds Crawford getting just one glimpse of the sun before she loses her vision again forever, culminates in a confusing jumble of images that only somewhat sells the audience on the idea that she fell out of a window.

"I made a lot of mistakes in that show, and eventually had the show, in post-production, re-edited by the producer of the show, which I guess was right because I was doing shots through chandelier baubles and I was doing reflections," Spielberg later admitted in an interview with legendary film critic Gene Shalit

"The whole New Wave European cinema had influenced me for my first network television debut, and New Wave European does not go along with NBC. It just didn't. In those days there was no common meeting ground," Spielberg said. "So I'm not really proud of the show but it was a great experience to be baptized that way."

'Eyes' am legend

Steven Spielberg's inexperience may have led to some production hiccups but it didn't hurt his career much. The episode earned Rod Serling an Edgar Award for Best Episode of a TV Series, and it launched "Night Gallery" into a successful three-season show. Spielberg continued shooting episodic television, including another "Night Gallery" episode two years later entitled "Make Me Laugh," which reunited the director with Tom Bosley and starred Godfrey Cambridge ("Watermelon Man") as a comedian who makes a wish to be hilarious but doesn't realize he may one day want to be taken seriously.

Spielberg would eventually find a more organic means of incorporating impressive cinematography in his television work. His excellent early episode of "Columbo," entitled "Murder By the Book," begins with a shot of a car approaching an office, and then pulls back to reveal we're in that office, as the camera pans across items that reveal all we need to know about the characters. It's a gag that's practically Hitchcockian in its marriage of visual ingenuity and storytelling practicality, echoing without exactly copying the opening of "Rear Window."

After cranking out episodes of shows like "Marcus Welby, M.D." and "The Name of the Game," Spielberg teamed up with frequent "The Twilight Zone" contributor Richard Matheson for the TV movie that became his first calling card, "Duel," about a hapless commuter terrorized by a homicidal truck driver. The rest, as they say, is history. At least until he makes a sequel to "The Fabelmans" about Sammy's television career. Then it'll just be a story.