The Taxi Driver Controversy Explained: How Martin Scorsese's Ultra-Violent Ending Shocked Audiences

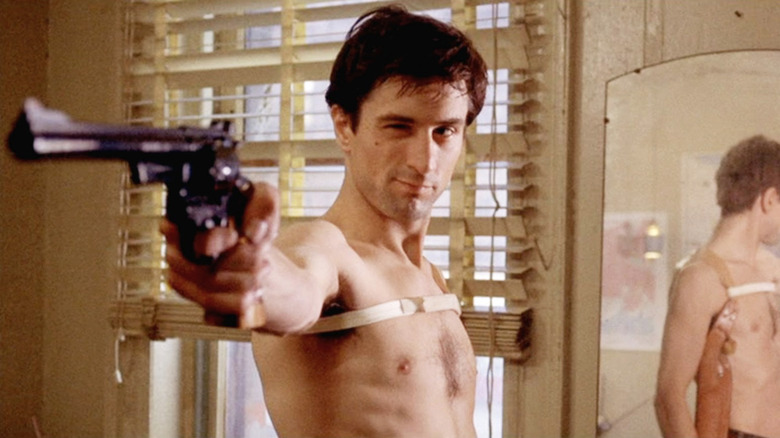

In Martin Scorsese's gritty drama "Taxi Driver," Robert De Niro stars as Travis Bickle, an unhinged, insomniac veteran and New York City cab driver. Travis channels his violent urges and obsession with a presidential campaign worker named Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) into a mission to remove the city of its sleaze and corruption, first by saving a twelve-year-old prostitute named Iris (Jodie Foster).

"Taxi Driver" is a haunting depiction of post-Vietnam isolation and nihilism, but it was met with boos during its screening at the Cannes Film Festival in 1976, and again while receiving the coveted Palme d'Or — "accompanied by a hand-wringing caveat that 'cinema not become a source of hatred,'" The Hollywood Reporter notes. There was so much contention surrounding the film during the festival that "Marty, Bobby and Harvey [Keitel] kind of got stuck at the Hotel du Cap and didn't come out very much," Foster recalls.

With a radical script from Paul Schrader, Scorsese's unflinching focus on a psychopathic loner and the degradation of New York City during that time period was too much for viewers to handle. His explicit portrayal of Travis' raging vigilantism drew the most controversy.

The Ending Was Too Violent

Travis fulfills his John Wayne rescue fantasy by gunning down Iris' pimp (Harvey Keitel), her client, and a bouncer. Bullets tear through their flesh, blood erupts from their wounds and splatters everywhere. This graphic display of Travis' cold-hearted slaughter drew the most criticism and left viewers "ashen-faced" at Cannes, especially the famous playwright Tennessee Williams, who served as the jury head. "Watching violence on the screen is a brutalizing experience for the spectator. Films should not take a voluptuous pleasure in spilling blood and in lingering on terrible cruelties as though one were at a Roman circus," he said (via THR).

The violence was also too much for the MPAA; in order to receive an R rating instead of an X, Scorsese had to desaturate the color during the shootout sequence to tone down the blood's realism and vibrancy. Scorsese was pleased with the results, but the cinematographer Michael Chapman confessed in a "Taxi Driver" DVD Commentary that he regrets the decision — especially because the original print without the color changes no longer exists.

The carnage in "Taxi Driver" is somewhat tame by today's standards, but the controversy surrounding it attests to the anxieties of that era. During the 1970s, there was a rise in crime, terrorist attacks, and increased reports of serial killers that put Americans on edge. Throughout the Vietnam War, which ended just a year before the release of "Taxi Driver," the horrors of Vietnam flickered on American television screens every night. The wounds of this violent culture were still too fresh for audiences to easily be able to consume such savage bloodshed on screen.

Travis Is Seen As A Hero

The ambiguous ending of "Taxi Driver" also drew controversy amongst film critics and audiences. After the shootout, an injured, bloodied Travis sits on Iris' couch and appears to be taking his final breaths. However, a thank you letter from Iris' father explains that Travis survives and is proclaimed a hero by the press and law enforcement. Travis successfully "washed the scum off the streets" and is rewarded for it with renewed attention from Betsy. Both Schrader and Scorsese insist the ending is not a dream and Travis does indeed live, despite the sequence's fantastical feeling.

When considering the "Taxi Driver" ending as reality, many film critics found it improbable and were disturbed by Travis' victory. "Most crippling is the ending, in which the macho movie cliche of the heroine who returns to the hero once his capacity for purgative violence has been revealed is crossed with the film's vaguest gesture of empathy with Travis," wrote Richard Combs in Monthly Film Bulletin (via Off Screen). Critics such as Combs failed to recognize that Schrader and Scorsese were not celebrating Travis, but commenting on the pervasiveness of crime during that era. In her New Yorker review of "Taxi Driver," Pauline Kael acknowledges the filmmakers' true intentions:

"This film doesn't operate on the level of moral judgment of what Travis does. Rather, by drawing us into his vortex it makes us understand the psychic discharge of the quiet boys who go berserk. And it's a real slap in the face for us when we see Travis at the end looking pacified. He's got the rage out of his system for the moment at least and he's back at work, picking up passengers in front of St-Regis. It's not that he's cured but that the city is crazier than he is."

Travis exists in a city and a country that is so riddled with violence that even a psychotic gunman can become a national hero. According to Paul Schrader on a DVD commentary, the media's lionization of Travis highlights America's sensationalism of violence and was inspired by Sara Jane Moore — the second woman who tried to assassinate President Gerald Ford — appearing on the cover of Newsweek (via The Take). "Taxi Driver" captured the 1970s zeitgeist with a daring aggression that shocked audiences and still resonates today.