Why Hollywood Needs To Embrace The Animation Revolution, According To Spider-Man Filmmakers

Among other reasons to bemoan the decline of traditional animation in the 21st century is the subsequent rise of the notion that the goal of animation should be to imitate real life as closely as possible. We saw this attitude manifest itself in mainstream computer animation throughout the 2000s and 2010s, which emphasized photorealism over stylization. But while the results were undeniably gorgeous at times (for example, the sequence where WALL·E and EVE "dance" among the stars in "WALL·E" is pure visual poetry), this mindset was inherently limiting. Why restrict yourself to reality when your imagination need not know any boundaries in animation?

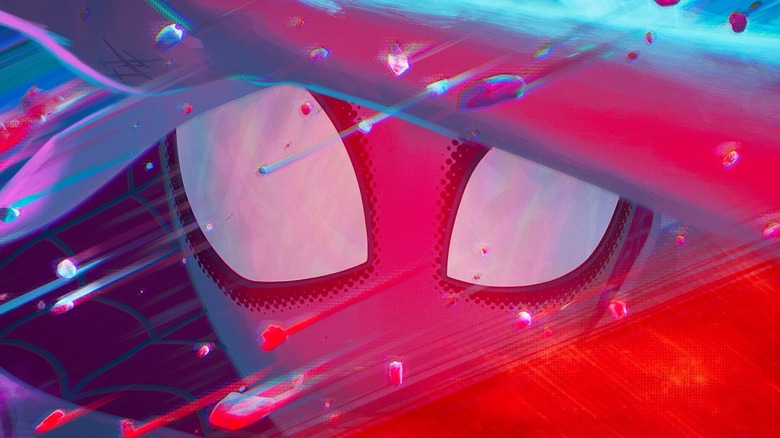

Thank goodness for "Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse." The 2018 superhero blockbuster not only mixed and matched animation techniques to create a heightened universe that could've come straight from the pages of an actual comic book, it also proved there was an audience hungry for animated films that eschewed the typical look popularized by Disney, Pixar, and the like. With the sequel "Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse," the creatives behind the first film only further pushed the limits of what computer animation is capable of visually. Luckily, they're not the only ones who've fully embraced the revolution "Into the Spider-Verse" ushered in, with DreamWorks Animation ("The Bad Guys," "Puss in Boots: The Last Wish") and director Jeff Rowe ("The Mitchells vs. the Machines," "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem") charging right alongside them.

Speaking at a press conference attended by /Film's BJ Colangelo, "Spider-Verse" series co-writers and producers Phil Lord and Chris Miller talked about how exciting it is for them to be part of the ongoing animation movement. As they see it, the only way forward is to keep proving to the money folk in Hollywood that experimentation is the future of animation, not a phase.

'The only limit is your imagination'

Lord and Miller came to fame as the co-creators of the cult animated sitcom "Clone High" in the early '00s before making their feature directing debut on the acclaimed 2009 animated hit "Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs." Calling animation "their first love" at the press conference, Miller emphasized that he and Lord regard animation and live-action as equals. "It's all about putting images and sound on the screen to convey a narrative and emotion and make you feel something, and they're just different ways of doing the same thing," he explained. He added that he's pleased to see more people realize animated films "don't all have to look the same, that cinema, these pictures that we're putting onto the screen, can look like whatever we imagine."

Continuing, he noted there's a historical precedent for this in the larger art world:

"And it feels a little bit like that time when, you know, for centuries, artists were trying to make paintings that looked exactly like reality. And then suddenly, when cameras started coming around, we had started getting Impressionism and Point and van Gogh, and then abstract expressionism and it exploded the world of what paintings could look like. And I think that's what's happening right now in animation — that the only limit is your imagination."

This very much parallels what's been going on in animation in the years since "Into the Spider-Verse" came out. Miller called it his and Lord's "mission to get studios, the people holding the money, to feel comfortable letting the artists make the films look the way they want them to look" while still turning a healthy profit. No doubt, it helps them that most of the experimental animated films that've come out recently have done precisely that.

Once more with feeling: animation is not a genre

Lord added that it's encouraging to see audiences flocking to films like "Across the Spider-Verse," only half-joking that they "made you know, an art film about Miles Morales into the third highest grossing U.S. release of the year." He also (rightly) argued that this hunger for innovation extends to live-action, pointing out that part of the reason "Barbie" and "Oppenheimer" become massive hits is that they're both "weird experimental films" at heart.

This led to him making another great point — "The history of animation and the history of cinema are one and the same," with animation having been a part of cinema since its earliest days. "Muybridge — watching those horses go across [...] He made essentially a lot of, like, pixelation films," Lord said. It's why he and Miller think it's "quite silly" to treat animation as a category separate from live-action, especially when it's "pushing the boundaries of artistry" by telling "incredibly well-told stories" featuring great music. "I just don't see any difference and I don't think the audience do either. And I think when we're in these awards seasons, we need to start thinking about these things as on the same playing field," he reasoned.

You're preaching to the choir, sir. For years, we here at /Film have called on the Academy to stop treating animation like an afterthought or a genre. Taking films as strikingly different as "Mutant Mayhem," "Suzume," "Elemental," "Nimona," "The Boy and the Heron," "The Super Mario Bros. Movie," "Ruby Gillman, Teenage Kraken," and "Across the Spider-Verse" (and that's just for 2023) and lumping them all into one giant pile is not just insulting to the artists who made them, it's also a strangely reductive way of evaluating cinema in general.