The Boy And The Heron Is So Personal, Miyazaki Changed The Story When Tragedy Struck

This article contains spoilers for "The Boy and the Heron."

As a prolific director and one of the co-founders of Studio Ghibli, Hayao Miyazaki has become one of the biggest names in animation around the world, possibly the best-known name outside of Walt Disney himself. But it's easy to forget about the other names behind Studio Ghibli.

Studio Ghibli was founded by Miyazaki, fellow director Isao Takahata, and producer Toshio Suzuki in 1985. By that point, the two directors had already spent 20 years working together. First, they worked on the financially disappointing yet hugely influential "The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun," as well as on Nippon Animation shows like "Heidi, Girl of the Alps," and "3000 Leagues in Search of Mother." It is a partnership that created a powerhouse in animation, and one that is at the heart of Miyazaki's latest (but no longer last) movie, "The Boy and the Heron."

The film has been in the making for seven years, and it is well worth the wait. Miyazaki's latest is not his best — but still a masterpiece — and a great goodbye letter from an all-time great filmmaker. What's more, this is Miyazaki doing his version of the trend of semi-autobiographical movies we've seen by popular directors in recent years — from Steven Spielberg ("The Fabelmans") to Kenneth Branagh ("Belfast"). Like Mahito, the main character of "The Boy and the Heron," Miyazaki evacuated from Tokyo with his family during WWII, which left a lasting impression on him. His father also worked at a company that manufactured components for fighter planes, and his mother died when he was young.

Except, it is not the same movie that Miyazaki set out to do. While this isn't uncommon (see the whole "Kingdom of the Sun" fiasco with "Emperor's New Groove"), this was different. The reason the movie changed is because of a real-life death.

A revolutionary partnership

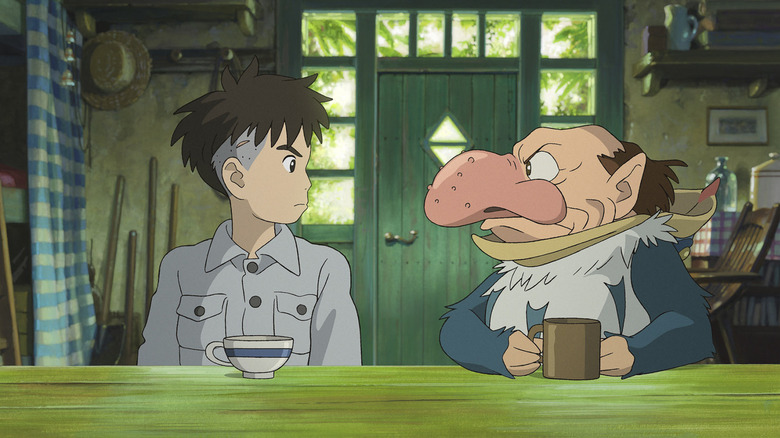

Speaking with IndieWire, producer Toshio Suzuki revealed just how personal the movie is for Miyazaki. "Miyazaki is Mahito, Takahata is the great uncle, and the gray heron is me," Suzuki said. "He said [Takahata] discovered his talent and added him to the staff. I think Takahata-san was the one who helped him develop his ability." He continued, "On the other hand, the relationship between the boy and the [Heron] is a relationship where they don't give in to each other, push and pull," basically describing the relationship between producer and animator.

The two first collaborated on "The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun," one of the first films to prove the power of anime as a medium. As Suzuki pointed out, Miyazaki spent the first 20 years of his career just following Takahata, like when the two ended at Nippon Animation and director Takahata brought Miyazaki on board as a storyboard artist and writer.

Their relationship was also one of rivalry — at times working together, others competing — as seen in the documentary "The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness." Takahata would criticize some of Miyazaki's writing, calling him "possessed" by his protagonists and unwilling to challenge them (via All The Anime). For his part, Suzuki once wrote in his biography "Kanyada from the Southern Country" that the first half of the relationship between Miyazaki and Takahata was almost like a "honeymoon," and described them as the "perfect duo." But later in life, the two would become more distant — yet still close.

Tragedy strikes

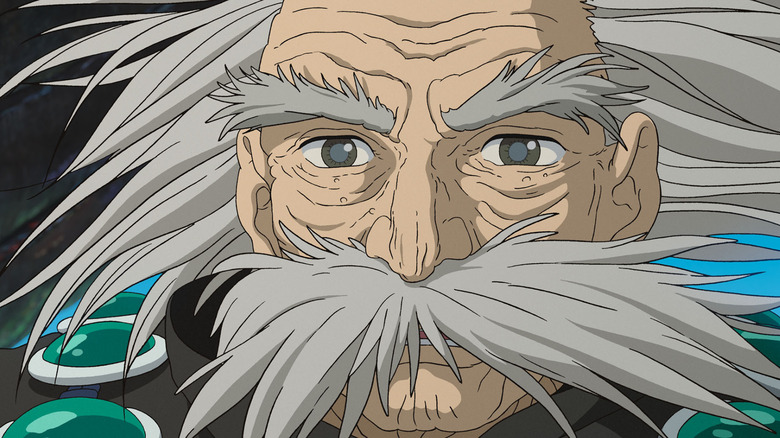

Regardless of fights and niceties, it is unfortunate that such a pivotal dynamic in Miyazaki's professional life is all but absent from his latest movie. In "The Boy and the Heron," the character of the great uncle is said to be important but only shows up until the very end of the film. This wasn't the original plan, but what Miyazaki was forced to pivot to after Isao Takahata died in 2018 — while "The Boy and the Heron" was in production. As producer Suzuki told IndieWire, Miyazaki was forced to scale back the role of the great uncle from a prominent and central part of the boy's story into barely more than a cameo, all out of grief.

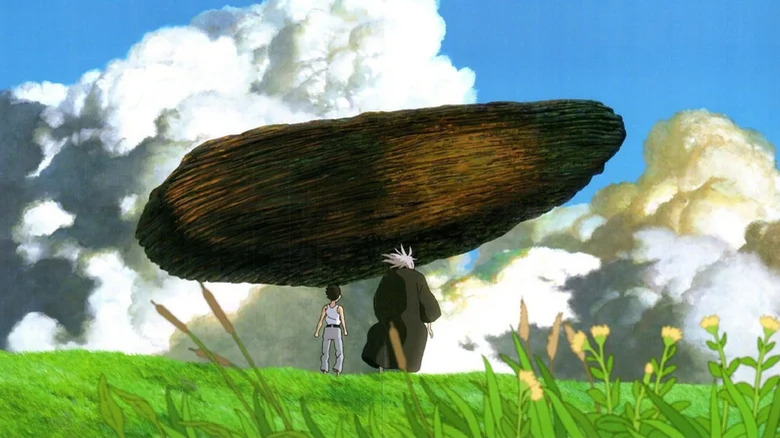

"After Takahata passed away, he wasn't able to continue with that story, so he changed the narrative and it became the relationship between the boy and the Heron," Suzuki continued. "And in his mind, initially, the Heron was something that symbolizes the eeriness of the mansion and that tower, even ominous, that he goes to during wartime. But he changed it to this sort of budding friendship between the boy and the Heron."

The film is so autobiographical that a scene where Mahito and the Heron sit and chat at a house by the water (the first image in this article) is a recreation of how Miyazaki and Suzuki would do their meetings. "The place that we do our meetings, where we have our conversation is at his studio, his atelier," he added. "And he has this like large table, but we don't sit facing each other, we sit next to each other, and we never look at each other when we talk. And what we discussed was very similar."

A longlasting friendship

It's not like Miyazaki hasn't infused his movies with aspects of his real life before. Many of his female characters were in part inspired by his late mother, and he made "The Wind Rises" as a tribute to his father's work. But seeing "The Boy and The Heron" not only as a goodbye letter to the world in case he doesn't make it to the next film but as a tribute to the partnership that gave him a career, is rather special.

What makes the film resonate even more, however, is the final moments of the film. Miyazaki does something similar to "The Fabelmans," where Spielberg uses the film to kind of reconcile with his parents after decades of using films to reckon with his feelings towards them. Here, Miyazaki reflects both on his career and the people who helped build it. When we finally meet Mahito's great uncle, he offers Mahito to take over his role as a wizard in charge of this fantasy world. It is a chance to escape the pain and grief of the real world, but Mahito refuses.

Instead, he goes back to the real world to face his trauma and live with it. For producer Suzuki, this ended up being the most surprising part of the film. "Miyazaki was someone who followed the path of Takahata for so many years, and I thought it was a huge thing for him [to follow a different path]."

Looking back, it doesn't seem like Mahito's decision necessarily reflects a desire or a pondering of what if Miyazaki hadn't followed Takahata. Instead, it seems like a farewell, an acknowledgment that Takahata now only lives in the fantastical worlds that Miyazaki dreams up. As long as he keeps doing so, his friend continues to live on.