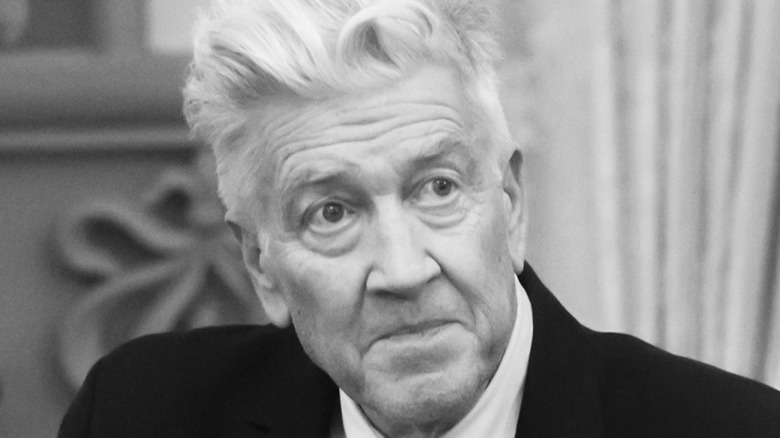

David Lynch's Feature Films Ranked From Worst To Best

Is there any other director as original as David Lynch? There are other directors who have proved as influential and recognizable (David Cronenberg, John Carpenter, and John Woo spring to mind) but none of them have an actual word to describe the many pretenders that came after ("Lynchian"). Aside from Hitchcock, there's no other director whose surname alone conjures up exactly what kind of film you are watching. Often imitated, rarely bettered, Lynch's films have made a lasting impact on cinema.

As a director, Lynch steadfastly refuses to explain his work, and prefers that his audience has an emotional response to his films rather than an intellectual one. The best way to experience a David Lynch movie is to let it wash over you, not delving into the minutiae to decipher its deeper meaning.

While many of Lynch's films share similar themes — personal duality, identity crises, and the clash between what we present to the outside world and to the darkness that lies under the surface — a few defy explanation completely. While we hold out hope for more Lynchian horrors in the future, for now, here's our ranking of Lynch's films, in order from worst to best.

10. Dune

Despite its abysmal reputation — and Lynch's own sadness about how the final film turned out – this adaptation of Frank Herbert's epic science fiction novel has its strong points. The set design is stylish and lived in, the costumes and casting are excellent, and the effects largely hold up. The problems come from the writing, which manages to be po-faced, muddled, and somehow both overlong and truncated, mainly due to the editing that butchers many characters' arcs. Although not entirely faithful to the book, "Dune" gets certain aspects completely right, albeit with additional Lynchian touches (the gigantic foetal space guild representative, Sting wearing metallic underpants).

Lynch's depiction of Herbert's worlds and larger-than-life characters would prove to be a major touchstone for adaptations going forward — the villainous Harkonnens' distinctive red hair is not present in the books, but was used in the 2000 Sky TV adaptation. "Dune" is worth seeing if only for the colorful performances, with Kenneth MacMillan's Baron Harkonnen being the living embodiment of repulsiveness, and Kyle Maclachlan's Paul Atreides striking just the right balance between likeable and imperious. The casting choices for the supporting characters are inspired, particularly Brad Dourif as the twisted assassin Piter DeVries.

The fact Lynch is able to give the film an epic scale despite his limited budget and the fraught production is a testament to his skills, but while some elements work, the whole is a mess. Compared to Denis Villeneuve's movie, Lynch's "Dune" looks worse as an adaptation, but taken on its own merits it isn't a terrible film.

9. Lost Highway

Lynch had toyed with neo-noir before, but "Lost Highway" represents a much more decisive step into genre territory. It's heavily stylized and beautifully shot, with the use of shadows and neon lighting evoking film noir just as much as the gangsters and the femme fatale. The premise — someone is arrested, then literally changes their identity in jail — surprisingly straightforward, and would be a strong premise for a more mainstream movie (you can see the kernel of the premise of Michael Haneke's "Cache" here, and more than a hint of "Vertigo" in the duality of the two characters played by Patricia Arquette).

The narrative is twisty and wonderfully atmospheric, but it doesn't grab your attention in the same way that the similarly themed "Mulholland Drive" does. Individual scenes are disorienting and creepy, particularly those involving the dead-faced Mystery Man (Robert Blake), a sublimely sinister, ethereal character.

However out of all of Lynch's movies, this is the only one that sometimes feels as though Lynch is self-consciously trying to make something "Lynchian," and it feels a little forced in places, at least when compared to the genuine unease of "Blue Velvet" and "Eraserhead." There are upsetting moments in Lynch's best films, but they always feel earned, or at least fitting in context. But in "Lost Highway," the explicit sex and gore feels a little gratuitous. "Lost Highway" does have an absolutely killer soundtrack, though, including songs by David Bowie, The Smashing Pumpkins and Nine Inch Nails.

8. Wild at Heart

This may be an unpopular placing, but Lynch's crime romance is very much an acquired taste. There are moments of genius, but this too often feels like an attempt to contain Lynch's undiluted weirdness in a fairly conventional narrative. As we will see, Lynch is more than capable of making straight films, but the ones that work tend to play down his more abstract flights of fancy. "Wild at Heart" feels like a half measure — it has a conventional plot but with so many non-sequiturs, loose ends, and plot points that burn out, it ultimately feels a bit incoherent.

At its core, "Wild at Heart" is a really sweet story about two characters who are very much in love, the Elvis-styled Sailor (Nicolas Cage) and Lula (Diane Lane), as they take to the road to evade Lula's gangster mother Marietta Fortune (a brilliantly unhinged Diane Ladd), who has sent an assortment of killers, lawmen, and bounty hunters after them.

Thematically "Wild at Heart" is an incredibly rich film, and some of the detours from the story are Lynch at his best (the vignette about Crispin Glover's Christmas-loving Jingle Dell is wonderfully bizarre), but it falls down on story. It's worth watching for an eclectic cast of colorful, bizarre characters, including performances by Harry Dean Stanton, Grace Zabriskie, Isabella Rossellini, Jack Nance, and Willem Dafoe as the villain, Bobby Peru.

7. The Straight Story

A David Lynch-Disney collaboration would raise eyebrows today, so you can only imagine the reaction in the late '90s, when Lynch followed up the explicit content of "Lost Highway" with "The Straight Story," a road movie filled with gentle humor. Referred to by Lynch as his "most experimental film," this sweet film follows the elderly Alvin Straight (Richard Farnsworth) who learns that his brother has had a stroke, and subsequently makes the long journey to visit him, travelling 240 miles from Iowa to Wisconsin on a lawnmower.

Amid Lynch's beautiful cinematography, Farnsworth, a classic Hollywood stuntman, turns in a wonderfully seasoned performance as Alvin, giving him a dignity that transforms the film into something that's really quite beautiful in places. Farnsworth was dying of cancer while filming, which lends the film an autumnal, wistful feel, even amidst the heartfelt comedy.

"The Straight Story" is the ultimate rebuttal to anyone who claims that Lynch can't do warmth. Where a lesser film might make Alvin the butt of the joke, Lynch instead depicts his encounters with curious bystanders as heartwarming and life-affirming. Just show someone the final reunion between Alvin and his brother (played by Harry Dean Stanton, in a characteristically taciturn cameo). There's no emotional outpouring and no dramatic speeches, but it still brings a tear to the eye.

6. Inland Empire

Some might find "Inland Empire" interminable, but to me this is an essential (if overlong) dose of Lynchian madness. Shot entirely on digital video, "Inland Empire" is Lynch at his most ambitious, completely abandoning any pretense of a conventional narrative and instead shifting into a series of vignettes surrounding Laura Dern as an actor shooting a new film, a remake of a supposedly cursed movie whose two leads were murdered.

Lynch's prevalence for duality and loss of identity rears its head again here, as Dern begins to think she is turning into her character, and the line between reality and fiction begins to blur. While certain scenes are disconnected from the main narrative, the whole nonetheless feels coherent. Still, the callbacks to earlier scenes are especially jarring, especially those featuring life-size anthropomorphic rabbits — not since "The Shining" have people in animal costumes been so disturbing.

Dern gives an intense, engaging performance as someone who finds herself struggling to keep a hold on reality. The moment when she runs in slow motion towards the camera is truly unsettling; Dern's panicked, distorted face is one of the most disturbing visuals of Lynch's career. At 180 minutes long, "Inland Empire" can be a bit of a slog, but it makes an impact, and might be the purest Lynch movie since "Eraserhead."

5. The Elephant Man

Lynch gives what could be a forgettable biopic a beauty and personality all of its own. Far from an accurate representation of the true story of John Merrick, Lynch mixes the poignancy of Merrick's condition with an industrial soundtrack and surreal, disturbing imagery taken from the urban legends that surrounded Merrick during his life.

Shot by Freddie Francis in crisp black and white, Lynch keeps Merrick at a remove, obscuring his face for the first half hour of the film, essentially putting the audience in the shoes of the gawking sideshow audiences. We are just as guilty as they are of wanting to see what's beneath the burlap sack he wears over his face. Once Lynch reveals John Hurt's Merrick, and he demonstrates his intelligence, his vulnerability, and his humanity, the film warms to him as well. Characters who initially seemed brusque or cold-hearted take on a very different tone, including Wendy Hiller's matter-of-fact matron and John Gielgud's upstanding chief doctor.

Anthony Hopkins would later say he found his role as the unfailingly decent Doctor Treves a bit dull, but his performance is gentle and subtle, miles away from his most famous roles. Hurt gives a painfully vulnerable performance, acting under prosthetic make-up that still holds up today, and manages to imbue his character with a child-like dignity that only occasionally veers into sentimentality. Poignant without ever being too maudlin, "The Elephant Man" is that rare thing: a biopic that is also a great film in its own right.

4. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me

Even after 10 feature films, "Twin Peaks" remains Lynch's crowning achievement. It's a truly unique TV show (back when that word actually meant something) centered on a central mystery: who killed Laura Palmer? The prequel film, "Fire Walk with Me," feels incredibly ahead of its time — notoriously unsuccessful on release, a reappraisal shows that "Twin Peaks" is one of Lynch's most evocative and genuinely unnerving films.

A big factor in the negative reception to "Twin Peaks" was the lack of screen time for series star Kyle MacLachlan's Dale Cooper. The film is more concerned with Laura (Sheryl Lee) in the days leading up to her death. As a prequel, "Fire Walk with Me" feels very different from the series. We know where the story is headed, giving the film with a tension and a sense of oppressive foreboding. Lee gives a natural, poignant performance as Laura that begs a big question — why wasn't she a bigger star?

The only reason "Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me" isn't higher on the list is because many important characters are absent — most notably Sherilyn Fenn's Audrey Horne — and some scenes, including a wonderfully unhinged performance by David Bowie, were removed, meaning that isn't a definitive version of the film. "Fire Walk with Me" may be violent and unpleasant, but it's never gratuitous. Instead, it's just deeply sad; the murder itself is almost operatic in its execution. While both "Twin Peaks" and "The Return" are excellent, revolutionary television, "Fire Walk with Me" is Lynch's most emotionally resonant film, and it shows the director at his most human and raw.

3. Mulholland Drive

Lynch's ode to Hollywood, "Mulholland Drive," may be the quintessential Lynch film, following amnesiac Rita (Laura Elena Harring) and newly arrived actress Betty (Naomi Watts) as they try to piece together Rita's identity. If this seems a touch straightforward for a Lynch film, don't worry. It doesn't take long for things to get weird.

Originally conceived as a TV series. "Mulholland Drive" is filled with Lynch's trademarks: larger-than-life performances, glossy cinematography, and some truly surreal sequences — not least of which is the vividly nightmarish "Man behind the Winkies diner" scene — all anchored by Watts' virtuoso performance. As a comprehensive study of Hollywood, Lynch covers all bases, from the bright-eyed ingenue to behind-the-scenes corruption and the pain of rejection.

Unsurprisingly, Lynch refuses to spell things out for his audience, and forces them to rely on their intuition to make sense of his films. There are multiple theories about what "Mulholland Drive" is actually about, with a comprehensive analysis provided on this very site. However, by the film's end, there is a sense of closure. It just feels like it makes sense. Lynch maintains that the story holds together if you pay attention, even going so far as to giving the audience cryptic clues on the DVD release. It's also full of a palpable nostalgia, with classic Hollywood actors like Lee Grant, James Karen, and Ann Miller playing supporting roles. "Mulholland Drive" is a beautiful puzzle of a film, and one that (unlike Lynch's more disturbing films) is eminently rewatchable.

2. Eraserhead

In the same way David Cronenberg described "The Brood" as his version of "Kramer vs. Kramer," "Eraserhead" could be Lynch's version of "She's Having a Baby." This is the director at his most undiluted, and despite its reputation as a weird arthouse film, the story is actually pretty clear cut, at least compared to Lynch's later films. While there are surreal Lynchian elements (the lady in the radiator and the moving, oozing chickens) at its core this is a story about a prospective father who is not ready to become a parent. It perfectly captures the anxiety and mania that take hold when a newborn baby arrives on the scene and utterly disrupts your life. The baby itself is one of the most chilling and horrifying representations of a newborn that cinema has ever produced — a grotesque, nightmarish creation that resembles something entirely alien. As the mother herself says, "They're still not sure it is a baby!"

The whole film has a jet-black sense of humor, and Jack Nance gets his best role as the title character, a man with a bizarre haircut and a perpetually confused expression on his face. It's pretty amazing that Lynch's style was so completely established in his very first film; the oppressive, industrial sound design would go on to be a staple of his work, and the monochrome cinematography gives this film a look entirely of its own. Incredibly disturbing, funny, and terrifying in equal measure, "Eraserhead" proved hugely influential, and is still one of the very best directorial debuts of all time.

1. Blue Velvet

One recurring theme in Lynch's work is the idealized setting that is rotten beneath the surface. This is summed up perfectly in the opening moments of "Blue Velvet": white picket fences and Bobby Vinton on the soundtrack as suburban homeowners water their gardens, only for the camera to slowly descend into the weeds, showing insects eating each other in gruesome detail. It's a macabre, surreal image to open on, and not the last one in this neo-noir masterpiece.

This contrast drives the whole film, as we see Jeff (Kyle MacLachlan, Lynch's perfect leading man) torn between the wholesome Sandy (Laura Dern) and the damaged Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini). It's a division that is made abundantly clear in the film's most celebrated scene, in which Jeff's Hardy Boys-style investigation is brought to an abrupt halt when Dorothy finds him hiding in her closet. From there, the film assumes an increasingly darker tone, as we are introduced to the gas mask-wearing Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper), one of cinema's most iconic villains — unpredictable, depraved and sadistic.

Lynch still retains his surreal sense of humor, though, exemplified in the scene in which Dean Stockwell mimes to Roy Orbison. It's perhaps the definitive Lynchian moment, funny, disturbing, and bizarre. Reminiscent of Hitchcock's "Shadow of a Doubt" in its depiction of the corruption of small-town innocence, with shades of "Rear Window" in its use of voyeurism, "Blue Velvet" is Lynch's most purely cinematic film. It mixes influences from melodrama, film noir, and classic Hollywood, and retains its ability to disarm and disturb its audience today.