The Unpopular Opinion: 'Prometheus' Is One Of The Boldest Science Fiction Movies In Recent Memory

(Welcome to The Unpopular Opinion, a series where a writer goes to the defense of a much-maligned film or sets their sights on a movie seemingly beloved by all. In this edition: a defense of Ridley Scott's controversial Alien prequel Prometheus.)

Like most of you, I walked out of my first screening of Ridley Scott's Prometheus in some combination of confused and angry. That was the Alien prequel we'd spent the past two-plus years anxiously anticipating? The film that absolutely wasted Charlize Theron and Idris Elba, featured some of the worst character beats I've ever seen in a science fiction narrative, and bled all over the memory of Scott's original Alien film? No matter how I approached the film – how charitable I tried to be in my interpretation of its story – all I saw was a barren wasteland where a promising Alien franchise might've stood. My hatred of Prometheus ran deep and pure.

And then a funny thing happened. A few months ago, as 20th Century Fox began to roll out new footage from Alien: Covenant and people in my social network started talking about Prometheus as if it wasn't the worst thing since death and taxes. A few friends even argued passionately on the film's behalf, suggesting that Prometheus, despite its flaws, was one of the boldest science fiction films to hit theaters in a good long while. This put me in an awkward position. I had spent more than four years nursing my grudge towards Scott's film, and while I remained convinced that the film would only get worse on a re-watch, I knew it would be disingenuous of me to argue against the film without at least giving a second shot.

So I popped Prometheus into my Blu-ray player again, and wouldn't you know it? That movie grew up a helluva lot in our four years apart.

Granted, Prometheus still has its flaws. That entire sequence with the two scientists in the Engineer's control room? Charlize Theron running in a straight line from a collapsing spaceship? Borderline unwatchable. But what I found is that the ability to anticipate those flaws meant that I focused less on the things the film did wrong and more on what the film got right. And my goodness, does the film get a lot right. From the visual effects to Michael Fassbender's masterful performance to Prometheus's philosophical mean streak, there are sound and logical reasons to argue that Ridley Scott's film might be one of the better science fiction movies of the last few years. And thankfully, I'm here to defend the poor, helpless $130 million studio film.

What’s Old Is New

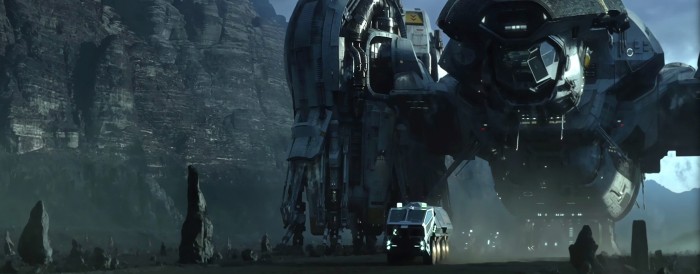

Because I was taught to look for common ground above all, let's start with a point I know we'll agree on. No matter how much you hate or love Prometheus, you can't deny the beauty of its production design. Scott's film is often breathtakingly beautiful: in David's quiet journey around Prometheus as his shipmates stay in hibernation and in the holographic universe that explodes out from the Engineers' control center, Ridley Scott demonstrates that it is possible to be an iconic filmmaker well into your seventies. Even the planet LV-223 is a marvel of both digital and practical effects, from the metallic terrain the Prometheus crew regularly traverses to the pre-Mad Max: Fury Road dust storm kicked up in the second act. There's not an element of the film's production design that hasn't been carefully thought out beforehand.

But for as much effort and energy went into making Prometheus a first-rate blockbuster, what stands out on repeated viewings is how carefully Scott's team balanced their visual effects against the precedent set by the original Alien film. Call it the Star Wars dilemma: with modern studios looking to remake or reboot many of their successful franchises from the '70s and '80s, audiences often find themselves puzzling over the anachronistic visuals of the latest films. Why are the starships of Star Wars: A New Hope so rectangular and rundown while the starships of Star Wars: The Phantom Menace are shiny and chrome? Why do the space stations of the 2009 Star Trek run circles around anything in the original series? I'm not talking about plot holes; I'm talking about a visual aesthetic that often puts contemporary films at odds with the franchise they are meant to emulate.

No good modern science fiction film will risk their box office for an authentic DOS computer screen – well, no good science film outside of Space Station 76, I suppose – but Prometheus does a remarkable job of creating a well-worn universe. Nowhere is this more evident than in the alien spacecraft's holographic replay system. Using old televisions as a reference point, Scott's VFX team was able to create an effect that was both decidedly modern – holographic rendering – and as worn out as anything we'd seen in the original Alien film. This was also echoed in the 3D mapping performed by the Prometheus and its crew; the environment is not created as a full video display but as model built out of a million different data points. It may look like a million bucks, but it feels a little anachronistic in a manner that serves the film well.

Oh, and don't forget the Engineers themselves. While not quite on par with the hulking creature we saw at the beginning of Alien, the Engineers of this film are fascinating character models who manage to convey both human and inhuman elements in the design of their features. Scott's team wisely chooses to downplay digital effects in the facial construction, further linking the past and the present together through a few smart tweaks to their scope and scale. They didn't quite sit with me right the first time, but after a few additional screenings and a little bit of reflection, it's a creature every bit as memorable in its own way as Giger's xenomorph designs.

The Story of David

If we can find some common ground on the film's special effects, then we may also find that we agree on Michael Fassbender's performance as the android David. While Noomi Rapace's Elizabeth Shaw is present for most of the movie's most lurid beats, it is David who serves as the true protagonist and our host for the film's most iconic moments. David carefully dying his hair as he sits enraptured by Peter O'Toole in Lawrence of Arabia; David pausing as the holographic character explodes around him; David (or David's head, rather) quietly goodbye to his creator as the remaining Engineer seeks his revenge against humanity. Prometheus is about David's journey from Pinnochio to, well, a real, live boy, and Fassbender has committed himself to this performance in a way we rarely see from most actors.

What's remarkable about David is his humanity, not his inhumanity. There's more than a little Rutger Hauer in Fassbender's performance; the actor lets soft expressions and strict posture keep him at odds with the crew around him, but you never question the character's agency. For most of the film, David gawks at the world around him with a sense of childlike wonder. But even if he weren't programmed to follow the instructions of his creator, you get the impression that David would find his way to betray Shaw and the other members of the crew more quickly than not. It's not personal, after all. It's merely evolution.

His own evolution, of course, explains much of his initially confusing betrayals. Just as the humans in the film are quick to turn on their gods when they discover the Engineers are more enemy than benevolent being, David's own quiet acts of rebellion are those of a child who has discovered his parents' weaknesses for the first time. And once you lean into the bleak worldview of the film, you may find yourself strangely pleased by its uncomplicated resolution. So much of Prometheus boils down to daddy issues, but what else would drive a brain of his ilk? For Prometheus to find hidden poignancy in this narrative would be to undermine the core values that Scott's film holds dear. It is, after all, a film about disappointments.

Anti-Science Fiction

In fact, Fassbender's role leads to one of the great strengths of Prometheus: its rejection of a tradition of science fiction philosophy. In March 2010, just a few months after Scott's Alien prequel was announced, iO9 founding editor Charlie Jane Anders published a piece on why the science fiction and humanism made for odd bedfellows. Futurism has always affirmed the very tenants of what it means to be human; as Anders noted in her piece, this often meant defending humanity's place on a spectrum between gods, who would revert us to "an earlier state of development," and machines, who would cause us to "abandon our humanity altogether." Countless science fiction stories have sent mankind into the stars only to reaffirm the very notion of what it means to be human.

Not Prometheus. The film not only flatly rejects the notion that humanity will earn a spot at the cosmic table, it takes the argument one step further and suggests that our entire existence was a mistake, a rounding error in the space arithmetic of the Engineers. How is it possible that we have a $130 million summer blockbuster that ends with humanity desperately fighting against the genocidal urges of its gods? That suggests that there is no spark of divinity in humanity, only the misguided alchemy of a biological weapon? I don't understand how we ask Hollywood for uncompromising visions and then denounce a film that bares its teeth in contempt toward the entire canon of science-fiction classics. Pick whatever adjective you will to describe Prometheus – bleak, nihilistic, and austere each come to mind – but don't you dare describe the film as playing it safe.

Consider a scene between David and Logan Marshall-Green's Holloway. Holloway, who traveled to the stars expecting a direct confrontation with mankind's creators, has turned to drink at the discovery that the Engineers on LV-223 have been dead for thousands of years. Holloway's relationship with David has been understandably tense through the film; he views David's creation as a bridge too far in the field of robotics and isn't pleased that David is the one who has come to cheer him up. "Why do you think your people made me?" David asks by way of conversation, to which Holloway spits back, "We made you because we could." Pausing a beat, David quietly reflects on this answer. "Can you imagine how disappointing it would be for you to hear the same thing from your creator?"

Damn. I mean, damn. Mankind has always tried to push the boundaries of its creation; we construct artificial intelligences, clone extinct animals, and cryogenically freeze the dying and the dead in the hope that we may one day hold dominion over life and death, all in the name of advancing science. And yet, we never stop to think that our creators might have pursued the exact same course. We created David and his ilk because we could, but our own creation? Sure, surely we must be special, touched by the hand of the divine. That sentiment lasts until the precise moment that David's head is ripped from his body by the remaining Engineer. In space, no one can hear your belief systems shatter.

More Than Just an Alien Prequel

And there is, paradoxically, the film's biggest flaw. The most common complaint by Prometheus detractors is that Ridley Scott's film effectively ruined the Alien franchise. I happen to think it's the other way around. Subsequent viewings of the film make it clear that there are two competing forces at work in Scott's film: there's the philosophical debate surrounding humanity and the cruel nature of gods who construct life simply because they can, and there's the origin story of the xenomorph, the Alien franchise's beloved monster. Only problem? The parts of the movie that work best are the ones that have very little to do with Prometheus' prominent billing as an Alien prequel.

Those with long memories will rightly point out that Prometheus began life as an Alien prequel, but even as the film moved through the development cycle in 2009 and 2010, it became somewhat clear that Scott had other things on his mind. "I'm explaining who the space jockeys were," Scott told MTV News back in 2010, while also noting that his film would be about "the discussion of terraforming." In January 2011, Deadline featured an exclusive report that Scott's film had subsequently evolved into a "more original" story, with Scott himself defending the "grand mythology" that had emerged from the film's development process. According to Scott, Prometheus would be "unique, large and provocative."

Whether those so-called "strands" were included at the behest of Ridley Scott or 20th Century Fox is up for debate; in interviews, screenwriter Jon Spaihts has claimed that it was actually the studio (huh) that pushed for Scott to "focus on the new mythology of Prometheus" and dial the Alien connections as far back as he could. Regardless, Prometheus ends up as the rare project where the monster bits are the least interesting elements of the film. By the time the film was released, fans had spent two-plus years dreaming of a modern Alien film and worrying over the fragmenting narrative surrounding the film. When they sat down to watch for the film for the first time, then, it was all-too-understandable that their opinions were anchored in how Prometheus failed to live up to the Alien hype, not how it managed to excel as an original science-fiction story.

Let me put it to you like this: what are the most frustratingly nonsensical elements of the movie? The scenes where Fiefeld (Sean Harris) and Millburn (Rafe Spall) are attacked by space snakes in the spaceship wreck comes to mind; Fiefeld's inexplicable reanimation and assault on the Prometheus crew; even Shaw's surgical extraction of the proto-xenomorph, while memorable, feels out of sync with the movie going on around it. But which elements of the film also closely resemble the violence of the Alien franchise? Yep. Had Prometheus been given more latitude – by studio, screenwriters, or filmmaker – to step outside of Alien's sphere of influence, we may rightly view this as an important film. Instead, Prometheus is left to people like me to defend it.

Final Thoughts

Perhaps the final piece of evidence for all that I've put forth is this weekend's release of Alien: Covenant. Billed frequently (and loudly) as a return to the horror genre, Alien: Covenant shares many of the same strengths and weaknesses outlined above and suffers a similar fate to its predecessor. As a sequel to Prometheus, Alien: Covenant shines; as a prequel to Alien, it does not. I remain as convinced as ever that Ridley Scott just missed giving us a new science fiction franchise as iconic as his original Alien film by tethering his storytelling to the fate of the xenomorphs; at least now we seem to have reached a point where Prometheus's brush with greatness is getting the attention it deserves. Scott may not have created a perfect science fiction film, but with a little bit of hindsight – and a willingness to bob and weave around the bad bits – you may just find he's made a science fiction film that's perfect for you.