The 15 Best Set Pieces In Brian De Palma Films

Brian De Palma is the undisputed king of the cinematic set piece. He's a technical genius when it comes to filmmaking, and while he's not maintained the consistency of some of his contemporaries, he has proven to be an important influence on later directors including Quentin Tarantino, Terrence Malick, and Noah Baumbach among others. He also has an innate sense of cinematic storytelling, using his technical ability to communicate meaning through the use of creative camerawork and editing.

Where De Palma truly excels is in self-contained cinematic moments. In some cases, these set pieces redeem the film in which they appear, while others are elevated to masterpiece status. There's a kinetic, dynamic feeling to these sequences, where the editing, music, and performances all work together in perfect cohesion. The choices for the best set pieces in this list are not definitive, but rather a handful that stand as quintessential De Palma.

15. Snake Eyes (1998) - The opening shot

"Snake Eyes" has been much maligned over the years, and a lot of this is deserved. That being said, Brian De Palma has always been a director who thrives on the technical side of things, and the opening shot shows he'd lost none of his ingenuity. Beginning with a TV news report on screen, De Palma pulls us back into a stadium and seamlessly merges into a 12-minute seemingly uninterrupted Steadicam shot. It follows corrupt detective Ricky Santoro, played by a wonderfully animated Nicolas Cage, who almost worked with De Palma again on a canceled "Untouchables" prequel. As Santoro interacts with several characters, only breaking from the shot once the assassin's bullet finds its target. It's a sequence full of De Palma's signature style, with incidental details gaining greater significance later on.

There's a sense of misdirection to "Snake Eyes" which gets clearer as the subterfuge of the fight becomes apparent. The pre-fight events are continuously replayed "Rashomon"-style as the film goes on, so it's fitting that we initially see everything in one go. It's like a magician showing you the trick before explaining how he did it. It's a superbly frenetic start to the film, one that draws attention to itself as audacious, unsubtle, and very fun.

14. Blow Out (1981) - Recording sound

Not a particularly dramatic or audacious sequence, but one that feels uniquely suited to De Palma's distinct talents. After a tongue-in-cheek opening that pokes fun at the director's own style, sound technician Jack (John Travolta) is ordered to record some new sound effects. De Palma takes you through the various noises Jack records with his rifle mic, utilizing painstaking attention to detail.

He initially hears a candid conversation between an unsuspecting couple, then picks up sounds from an owl and a frog, and De Palma uses vividly stylized split-diopter shots to illustrate these. It's disarmingly charming, reminiscent of the fairytale aesthetic of "The Night Of The Hunter," until Jack hears a noise he doesn't recognize, a whirring clicking noise that is later revealed to be the wristwatch garotte of the sinister hitman. It clearly unnerves Jack and, as if to amplify this, De Palma stubbornly refuses to cut to the source of the noise, instead showing us a disquieting shot of some bushes. Suddenly, in a chilling moment, the noise stops. The tension is broken by the subsequent car crash that provides the groundwork for the film, but this beautifully edited scene — the calm before the storm — is what sticks in the memory.

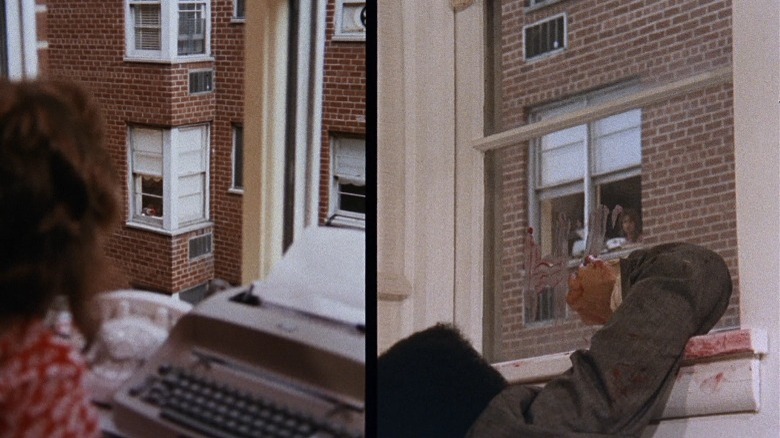

13. Sisters (1972) - Splitscreen

The pivotal murder scene in "Sisters" remains one of the most shocking moments of De Palma's career, and it works largely because all the elements are brilliantly set up. De Palma both lulls you into a false sense of security and carefully builds a palpable dread, with several details coming together amid the fateful moment. The set of steak knives, the pills accidentally knocked down the drain, the argument between sweet Danielle (Margot Kidder) and her unseen sister, all seem incidental until amiable Phillip (Lisle Wilson) is abruptly stabbed to death. It's a jarring, brutal moment, made even more jolting by Bernard Herrmann's piercing score, recalling his own work on "Psycho."

Even more impressive is the subsequent scene, where De Palma splits the screen from the moment Phillip scrawls "Help" on the window in his own blood, witnessed by a neighbor (Jennifer Salt). It's an extended scene, incredibly well-timed and choreographed, and features a surprisingly subtle moment as Danielle catches a brief glimpse of her reflection with a line right down the middle, hinting at her own fractured psyche.

12. Dressed To Kill (1980) - The gallery

Proof that not all of De Palma's set pieces end with a shoot-out or a murder (that comes later), this scene is the perfect demonstration of his command of visual storytelling as he gets into the headspace of the sex-starved Kate Miller (Angie Dickinson). A uniquely cinematic sequence with virtually no dialogue, this is effectively a seduction, with Dickinson and a handsome stranger alternating between predator and prey as they observe each other walking around a labyrinthine art gallery. It's masterfully constructed, with De Palma clearly laying out the geography of the gallery, and Pino Donaggio's emphatic score lending the scene an ethereal, overly melodramatic feel that fits perfectly with Dickinson's frustrated, daydreaming character.

This all feels like a prelude to a murder, and in a way, it is: If you look closely, the film's killer appears in the middle of a long tracking shot, and at the very end of the sequence we see them pick up Dickinson's discarded glove. It's a disquieting end to an enthralling set piece, and feels like the closest thing to an American Giallo, specifically in the way the mundane setting is given an almost imperceptible yet potent sense of dread, where the anticipation of murder is just as important as the kill itself.

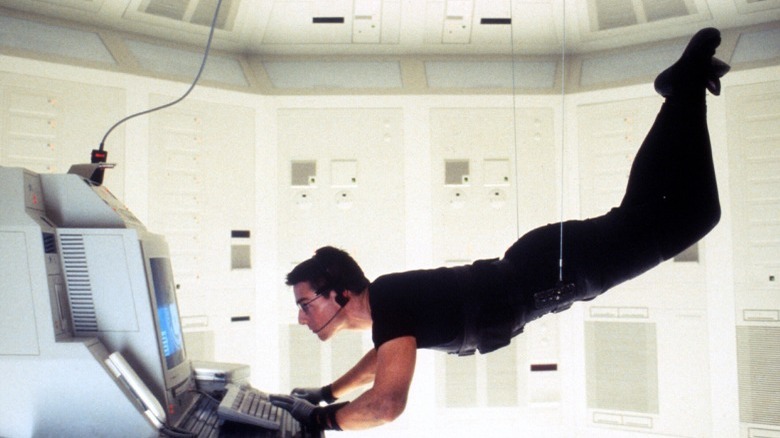

11. Mission: Impossible (1996) - The heist

In many ways, the original "Mission: Impossible" remains the most subversive and unique of the entire series, despite the advances in technology. This is De Palma's most uncharacteristically crowd-pleasing film, and he manages to thrive within the limitations of the studio system all while subverting the very idea of a blockbuster. The heist at CIA headquarters is, fittingly, a seemingly impossible task. The futuristic, sparsely designed vault is equipped with sensors to detect any noise above a whisper, shifts in temperature, and — most importantly — any pressure applied to the floor. That latter detail is where the iconic wire work comes in.

De Palma is clearly influenced by Jules Dassin here – specifically "Topkapi" in the use of wires to get into the vault, and "Rififi" in the way De Palma lets the heist unfurl in silence. This only adds to the tension, as you can hear a pin drop for most of the scene, making the moment where Hunt is accidentally dropped to just a few inches off the floor even more nail-biting to watch. Later films in the series would focus on increasingly spectacular stunts and effects, but it's this relatively simple stunt that provided the franchise with its most enduring image.

10. Scarface (1983) - The chainsaw

"Scarface" is a film that is full of decadence and excess, from the colorful costumes to the melodramatic plot and larger-than-life performance from Al Pacino as Tony Montana, so it's interesting that the most notorious moment is actually an exercise in restraint from the director. In an attempt to make Tony talk, the Colombian gangsters take a chainsaw to the arm of the hapless Angel (Pepe Serna).

While it's admittedly horrific, what's notable is how little we see onscreen. Brian De Palma keeps his camera on Angel until the moment the chainsaw cuts into him. We see a brief bit of blood on Angel's face then it immediately cuts to Tony's disgusted reaction. De Palma manages to get away with a lot by essentially alluding to what's just happened, the only real confirmation of which comes when the lead gangster malevolently says "now the leg." There's a lot of blood, but De Palma never lingers on the violence, instead choosing to show Tony's steely resolve. He's not a nice guy by any means, but this scene establishes him as a character of iron will and determination, and it's difficult not to cheer him on when he takes his revenge.

9. Carlito's Way (1993) - Carlito's trick shot

From the moment Carlito (Al Pacino) enters this seedy basement, filled with dodgy-looking gangsters, we know he and his cousin (John Ortiz) are in danger. The gang's protestations that the toilet is "out of order" ring false, but Carlito recognizes this too, and we immediately want to know how he will get himself and his cousin out of this volatile situation. The answer is ... he doesn't.

It's a sequence that fizzes with kinetic energy as Carlito starts cockily setting up his "trick shot" on the pool table, joking around and moving perfectly in time with the music and the increasingly fast editing. This flamboyance is all an act, a distraction that's methodically laid out by De Palma with characteristic clarity. Carlito sets up his shot so he can keep an eye on the back door reflected in the sunglasses of a gang member opposite. The minute he sees the concealed hood emerging from the bathroom, Carlito springs into action. As the music gets louder, he shoots the leaders and immediately takes cover in the bathroom where, having run out of bullets, he uses his wits and bravado to scare the surviving gangsters away. Carlito does everything he can, but it's too late to save his cousin. At its core, "Carlito's Way" is a film about leaving the criminal life behind, and this beautifully constructed sequence is the perfect distillation of exactly why Carlito needs to get out.

8. Phantom Of The Paradise (1974) - Upholstery

Brian De Palma's rock opera medley of "Phantom Of The Opera," "Faust," and "The Picture Of Dorian Grey" is set to an insanely catchy soundtrack by Paul Williams, who has a lot of fun reworking his own songs into different styles of music, from slick crooners to proto-heavy metal. In this scene, he reworks the film's main "Faust" theme into a frivolous Beach Boys-style song, "Upholstery."

No longer content with emulating Hitchcock (although he does later do a brief homage to "Psycho"), De Palma takes a leaf out of Orson Welles' book by reconstructing the iconic opening of "Touch Of Evil," where the camera follows a ticking bomb in the boot of a car in one long uninterrupted take. Here, The Phantom plants a bomb in a prop car used during rehearsals, as the characters sing the upbeat song with the ticking continuing on the soundtrack. De Palma goes one step further, though, doing all this and adding a split-screen. The result is a virtuoso sequence, as characters chatter and bicker over the song, walking from one shot into the other, all building to the inevitable explosion, as Swan (Williams) catches the briefest glimpse of the Phantom on an opposite balcony. It's an exceptionally choreographed sequence, and De Palma never once loses track of his characters.

7. The Untouchables (1987) - Malone's death

Sean Connery's Irish cop is the irascible heart of "The Untouchables," who's willing to get his hands dirty to put Al Capone (Robert DeNiro) behind bars. Unfortunately, Malone's digging costs him his life, in one of the film's stand-out scenes.

De Palma initially misdirects the audience by showing Capone's chief assassin Frank Nitti (played with a sadistic glee by Billy Drago) waiting outside Malone's apartment, before walking away, leaving his knife-wielding henchman to break in. We are put squarely in the gangster's shoes as he plays a game of cat and mouse with Malone, watching him go from room to room until Malone spins around with a shotgun, seemingly gaining the upper hand. He derides the gangster, telling him he's brought "a knife to a gunfight." He then unceremoniously chucks the gangster out, only to be confronted by Nitti, who's been lying in wait the entire time and mercilessly guns him down.

The aftermath of the scene, as Malone agonizingly crawls to his living room, is contrasted with Capone being informed of the hit while weeping a solitary tear at the opera. His carefully cultivated facade of sophistication is brilliantly undermined by the cuts to Malone bleeding out on his carpet. Subtle? No. Effective? 100%.

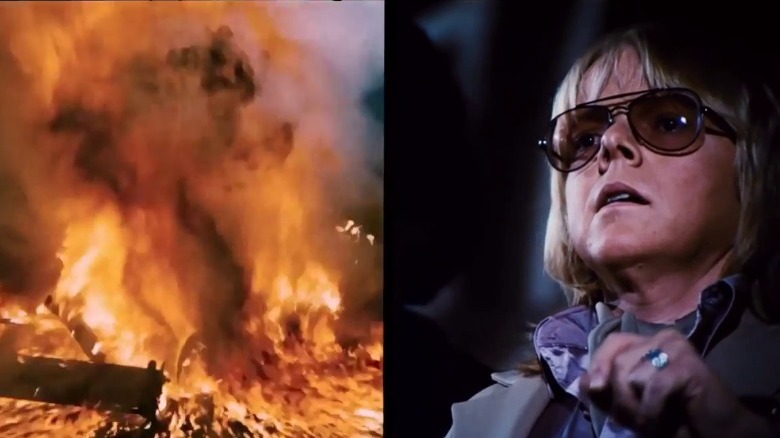

6. The Fury (1978) - The ending

The big finale to "The Fury" (an eclectic hodge-podge of supernatural horror and espionage thriller), is one of the most morbidly satisfying moments of his oeuvre. Throughout the film, Ben Childress (John Cassavetes) has been unapologetically evil, setting up his friend, abducting his gifted son, and ultimately contributing to their deaths. Having taken the similarly gifted Amy Irving into his "care" he comforts her, unaware that she knows of his true nature. What follows is one of the most spectacular death scenes in cinema history, as Irving uses her telekinetic powers to first blind Childress, then blow him up from the inside out. It's horrific, gory, and a technical marvel.

De Palma is showing off here, shooting the explosion from multiple angles (shown 16 times in total) making you feel the full force of it. It's a clear antecedent of the iconic head explosion in David Cronenberg's "Scanners," but unlike that film, this doesn't feel like a horror scene. It's more reminiscent of the Death Star blowing up, as it's actually cathartic to see this abhorrent character's downfall in the most spectacular way imaginable. De Palma clearly agrees as John Williams' score is positively celebratory, as Childress' body parts litter the room in slow motion. A macabre ending to a very strange film.

5. Dressed To Kill (1980) - The elevator

Angie Dickinson's character pays the price for infidelity in the most extreme way in "Dressed To Kill," when her afternoon fling turns into a nightmare. This sequence feels ominous from the start, as we can see Kate being watched from the fire escape by a mysterious blonde, but even then we are so invested in her personal problems that we don't suspect what's coming. De Palma spends so long getting inside Kate's head in this scene as she frets about her tryst, and then leaves her wedding ring and heads back up to the room, that we can almost be forgiven for forgetting the sinister figure on the sixth floor. That is until the elevator doors open.

In a scene that's still hard to watch, the mystery woman brutally slices Kate's hand open with a cutthroat razor before advancing menacingly towards her and repeatedly stabbing her. This murder is made even more chilling paired with the film's resolution, and the knowledge that Kate likely recognizes the killer, which is a terror that Dickinson performs perfectly. The scene ends with a moment that is pure De Palma, when the light glints off the razor into the eyes of the unsuspecting Liz (Nancy Allen), who catches the briefest glimpse of the murderer in the elevator mirror just as the doors close.

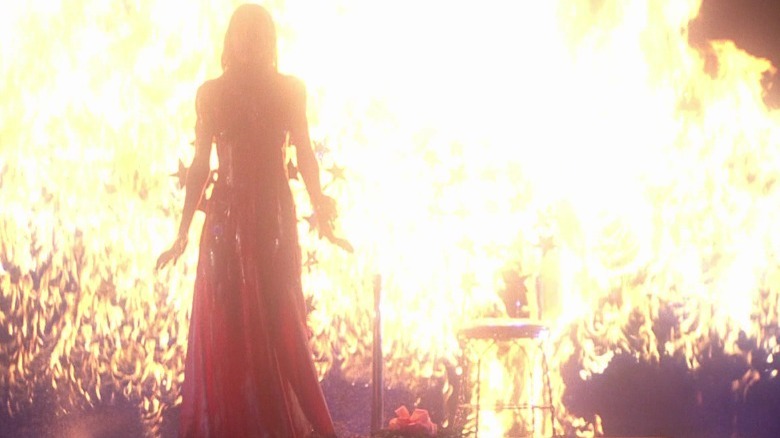

4. Carrie (1976) - The prom

The fateful prom night, where telekinetic social outcast Carrie White (Sissy Spacek) carries out her nastiest revenge, is one of the most iconic scenes in cinema. You're probably aware of it even if you haven't seen the film. It feels like the culmination of all De Palma's work up to this point through its meticulous construction, with every shot deliberately placed exactly where it needs to be. From the moment the bucket of pig's blood empties onto Carrie, De Palma is firing on all cylinders. The sound immediately drops out, as we see her classmates' stunned reactions until her mother's ominous warning begins to ring in her ears: "They're all gonna laugh at you."

In a neat touch, De Palma shows her mother's prediction coming true, even though it's clear that it's only the bullies laughing at her. When it cuts to her point of view, Carrie sees everyone at the prom pointing and laughing. It's a masterstroke that demonstrates Carrie's increasingly fractured mind and explains the indiscriminate revenge she takes on the entire school. Even 50 years later, it still remains one of his most striking set pieces. De Palma uses sound, mise-en-scène, and editing to put you completely in Carrie's mindset, perfecting the split-screen technique he utilized in earlier films to dazzling effect. The sequence is chaotic but nonetheless perfectly coherent.

3. Blow Out (1981) - The final chase

The final chase in "Blow Out" is the most heart-wrenching scene of De Palma's filmography, as Jack (John Travolta) desperately tries to catch up with Sally (Nancy Allen) and the psychopathic hitman Burke (John Lithgow), who is masquerading as a political reporter. Having wired Sally for sound, Jack listens through his earpiece for any clues on where they might be headed.

De Palma's editing and camerawork keep the sequence fast-paced and frantic, putting you squarely in Jack's shoes. He drops the sound out at crucial moments (where Sally says the name of the subway station and so on) and uses split-diopter shots to show him desperately patching the pieces of information together, eventually tracing them to the Liberty Bell Parade. Travolta is brilliant, sprinting from location to location as Sally remains blissfully unaware of the danger she's in until it's too late. Pino Donaggio's score might sound overwrought in isolation, but in context it perfectly captures Jack's anguish as he cradles Sally in his arms, the camera revolving around him as fireworks explode in the background. It's a downbeat, painful set-piece, and leads into that iconic final scene, with one of cinema's all-time grimmest punchlines.

2. Carlito's Way (1993) - Race to Grand Central Station

Certainly the longest sequence on our list, the climactic chase scene in "Carlito's Way" shows De Palma at his absolute best, as Carlito (Al Pacino) desperately tries to make the train that will take him to his new life, while also trying to elude the four vengeful gangsters on his tail. It's an incredibly high-energy foot chase, with De Palma continually weaving the camera around his actors as they move through the various settings, from Carlito's nightclub to a subway train, to the concourse at Grand Central. Every movement is carefully choreographed, right down to the tiniest detail.

The Steadicam is incredibly fluid as Carlito stops and starts his way down to the concourse, all the while avoiding the pursuing gangsters. When he finally makes his agonizing trip down the escalator, right under the eye of his pursuers, it's as if time stands still. We hear the bombastic score, see the final gangster spot Carlito, and register the look of resignation on Pacino's face. This should take a fraction of a second, but each moment is carefully timed for maximum effect. When the inevitable shootout happens, it feels like a giant exhale, as if we have been collectively holding our breath throughout the entire chase, and we're now back on more comfortable ground, watching Carlito dispatch his enemies with relative ease, all of which makes the film's final rug pull even more tragic.

1. The Untouchables (1987) - The pram

When the scripted climax to this gangster epic proved unfilmable, De Palma had to come up with an ending on the fly, and his solution proved one of the most cinematic, beautifully constructed sequences of his career. Out of necessity, it's almost entirely non-verbal, and the build-up is a masterclass in suspense as Eliot Ness (Kevin Costner) and George Stone (Andy Garcia) watch the clock, waiting for the gangsters to arrive, and scrutinizing everyone who enters the station. Ness is distracted by a mother struggling to get her pram up the steps, and in the ensuing gun battle the pram is knocked down the steps in a homage to Sergei Eisenstein's "Battleship Potemkin."

De Palma doesn't go for subtlety here, but the result is pretty spectacular. The geography of the scene is painstakingly laid out, and the shootout is the definition of organized chaos. As the gunmen are taken out, De Palma cuts quickly between Ness, Stone, the gangsters, and the pram without ever losing track of where anyone is. It's the ultimate De Palma set piece, with everything that entails: It's overblown, melodramatic, and fanciful, but also technically flawless and edited with precision and clarity that most directors can only dream of achieving.