Napoleon's Last Stand And The Battle Of Waterloo, Explained

There are a lot of hype moments in Ridley Scott's new film "Napoleon," but perhaps the biggest is in the final act when we get the reveal that the battle Napoleon's preparing for is none other than the showdown at Waterloo. All the ABBA fans in the audience leaned forward at that point, as did anyone unlucky enough to have read through the entirety of Victor Hugo's 1862 novel "Les Misérables" without skimming through that 50-page tangent about the battle in question. It's one of the most famous battles in world history, to the point where the name rings familiar even to those with only a vague recollection of 19th century France. This was the moment when Napoleon fell, after all. It's when the most important man in Europe for the past 20 years was finally forced into exile, for good this time.

But in the movie itself, the battle isn't conveyed particularly well. It hits on the broad points — how Napoleon lost, how the rain messed up his plans — but there isn't that strong a sense of direction throughout the whole thing. It's particularly strange for "Les Mis" readers, because say what you will of the book's Waterloo segment, but it definitely succeeds in making sure the reader knows exactly how and why things went wrong. Hugo presents the battle as one of the most important events ever, a battle that would've created a different world if it had gone in Napoleon's favor. Director Ridley Scott, meanwhile, presents Napoleon's Waterloo loss as just another thing that happened to him.

So, if you're looking for a slightly more in-depth explanation of the Waterloo battle, look no further. Let's start with the biggest point.

The rain really did ruin everything

"Had it not rained in the night of 17-18 June 1815, the future of Europe would have been different," Victor Hugo wrote about the day. "A few drops of water, more or less, were what decided Napoleon's fate." The reason for this was because Napoleon was first and foremost an artillery man, and the artillery weapons couldn't aim or maneuver well enough with the ground still damp and soft. His original plan was to begin his attack early in the morning, which hopefully would've allowed him to defeat the British army before the Prussian army could arrive with reinforcements. Instead, he had to wait until around 11:30 AM before the ground was dry enough, which made quite a big difference.

Although most historians agree that Hugo exaggerated his account of Waterloo slightly to make Napoleon look more favorable — not only was Hugo a Bonapartist, but he was a writer trying to make the battle as fantastical as possible — they still agree that he was pretty much spot on about the weather point. Not only did Napoleon have to delay, but the ground was still damp enough that mortars were less effective on impact. Napoleon's biggest strength, the thing that so easily led him to victory in an earlier battle, was effectively cancelled out.

Napoleon himself also had no trouble blaming the rain for his defeat in the years afterward. According to Andrew Roberts' 2014 biography "Napoleon," the emperor told a general a year afterward: "Perhaps the rain of the seventeenth of June had more to do than is supposed with the loss of Waterloo... Events that seem very small often have great results."

Napoleon might have had hemorrhoids

In addition to the weather, there were also some pre-existing health issues that might have played a role in Napoleon's questionable performance throughout the battle. "This might be the reason why he spent hardly any time on horseback during the battle of Waterloo," writes Andrew Roberts, "and why he twice retired to a farmhouse at Rossomme about 1,500 yards behind the lines for short periods." It's also noted that Napoleon had a record of suffering from bladder infections, narcolepsy, and general sleep deprivation, although it's unclear exactly how much any of this was bothering him at the time. "By June 18 he also had had only one proper night's sleep in six days," Roberts notes. This all might sound trivial, but considering how much of Waterloo's loss is blamed on unforced errors on the part of the French, it's worth keeping in mind.

Another pre-battle thing to note is that Napoleon made the criminal mistake of not taking a service worker's words seriously. His brother had told him that the waiter at a nearby inn, where the British commander dined mere days before, had heard news that the Prussian army was already on its way to join forces with the British. Napoleon ignored this "devastatingly accurate" information, Roberts writes, insisting that it wasn't possible for the armies to link up so quickly. Based on the version of Napoleon Joaquin Phoenix has just given us, it's easy to imagine the real Napoleon making the same blunder.

It just goes to show that you should always listen to your waiter. If they grimace when you order the fish, don't order the fish. If they tell you your enemies' armies are reuniting faster than you expected, don't just continue about your battle plans as you were before.

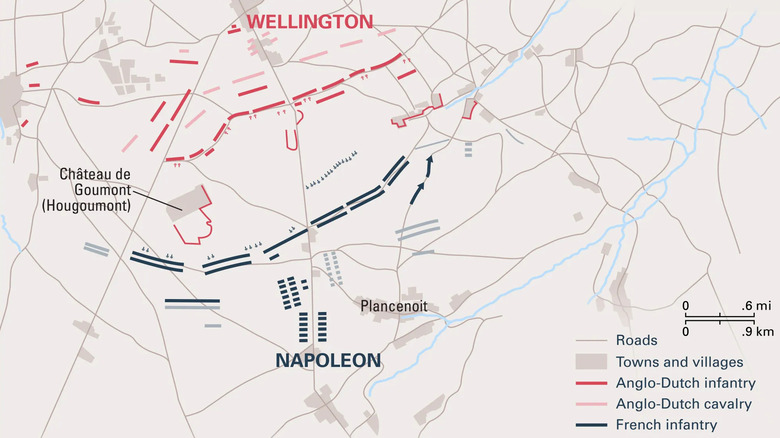

The attack on Hougoumont

One of the first unforced blunders on Napoleon's part was that he allowed his enemy to pick out the battlefield. It was the British commander, the Duke of Wellington, who had scoped out the area first and settled on it as the place to fight. The first area that Napoleon had attacked was the British-controlled Hougoumont, which was a manor well-fortified and garrisoned, which the French never managed to overtake at any point in the battle. "It was a fateful place, the beginning of disaster," Victor Hugo wrote, "the first obstacle encountered at Waterloo by the great tree-feller of Europe whose name was Napoleon, the first knot to resist his axe."

Hougoumont stood strong and Wellington continually reinforced it throughout the day to great success, turning it into "an invaluable breakwater that disrupted and funneled the French advances." Although the attack on Hougoumont was at least partially intended as a diversionary attack, designed to keep Wellington focused on the area at the expense of the positions in Wellington's center left, Hougoumont ended up being perhaps the most important part of the battle. At the very least, it definitely took the lives of a massive number of Napoleon's men. His brother Jérôme's division, which led that initial attack, lost more than half of its battalions.

Attacking the Anglo-Allied center

Soon, Napoleon had his General Comte d'Erlon attack "Wellington's centre-left," with "the hope of smashing through and then rolling up each side of Wellington's line," Roberts writes. "It was the correct place to attack, but the execution was faulty." Despite the fact that one of Napoleon's most famous maxims was that "Infantry, cavalry, and artillery are nothing without each other," d'Erlon failed to effectively combine the three forces. He failed to properly protect his infantry attack, which resulted in said infantry soon "fleeing back to the French lines."

What made things worse was that at around 1:30 PM, the first of the Prussian army began to arrive. While not entirely unexpected, Napoleon's choice to lie to his army about the circumstances only ended up making things worse in the long term. He ordered that his men be told the army on the horizon belonged to French general Emmanuel de Grouchy, who was separated from them at the time, but as Roberts explained, "As time wore on this falsehood was gradually revealed [to his troops], with a corresponding drop in morale."

Failing to take advantage of Le Haye Sainte

Despite the rain and the dropping morale, there was one last chance for Napoleon to still win the day, and that was the capturing of Le Haye Sainte, a walled farmhouse compound, as well as the "nearby excavation area known as the Sandpit in the center of the battlefield." If Napoleon had sent more troops to the area as soon as it was captured, there was still a chance they could've overpowered the British army "before the sheer weight of Prussian numbers crushed them," Roberts writes.

But even though Napoleon had 14 available battalions at the time, he didn't send them right away. When he did finally decide to send them half an hour later, the opportunity had passed. Wellington had already shifted his strategy in response to the capture of the compound, and sending in those reinforcements was no longer as effective as it would've been.

Napoleon didn't fully accept that the battle was over until around 8:00 PM that day, when his Imperial Guard made its final attack and was quickly forced to retreat. "Sauve qui peut!" soldiers were crying out, or "save yourself if you can." According to Roberts, Napoleon told a nearby general, "Come, general, the affair is over — we have lost the day — let us be off."

A deadly affair

In the end, Waterloo was the second deadliest battle in the Napoleonic Wars. "Between 25,000 to 31,000 Frenchmen were killed or wounded," Roberts writes, whereas there were over 24,000 casualties on the other side. It was a long, brutal mess, one that Ridley Scott's movie doesn't seem that interested in depicting. Perhaps the battle will be expanded a lot more in the four-hour cut we've been hearing so much about, and maybe we'll get to see some of the many other battles Napoleon commanded over his career (most of them victories fro the French emperor).

Then again, it's possible that the lack of extended focus on Waterloo comes down to the point Ridley Scott is trying to make with his main character. "Napoleon" is very much a critique of the Great Man of History trope, constantly subverting our idea of Napoleon as this brilliant charismatic genius every step of the way. Was Napoleon the best man to attempt this sort of subversion? Considering how popular (and factually inaccurate) it is to portray the guy as a short angry insecure dude, maybe not, but it at least explains the lack of emphasis on Napoleon's final battle.

This movie was never going to take Victor Hugo's approach of depicting Waterloo as a big, romantic, tragic clash between armies, because unlike Hugo, the creators of this movie don't seem to hold Napoleon in a high regard. This is a vain man doomed by his own ambitions, the movie tells us, so of course he's not going to win this one. In real life, Waterloo was a dramatic affair with lots of twists and turns for a movie to take advantage of, but in this movie? The battle is just karma for Napoleon's arrogance, not much more.