Every Main Character In Blonde, Ranked Worst To Best

Andrew Dominik's "Blonde" has finally made its worldwide debut, bringing with it the expected controversy. A success at the Venice International Film Festival, the film became one of the most critically polarizing arthouse dramas in years, inspiring both fervent defenders and mortified detractors to talk about it, write about it, and tweet scorching hot takes about it.

The reason for all the hubbub is plain: The film, adapted from Joyce Carol Oates' much-celebrated novel, takes a fictional approach to the life and times of one of the greatest Hollywood icons of all time, Marilyn Monroe — a stage name that "Blonde" pointedly positions as such, instead referring to the woman and listing her in the credits as "Norma Jeane." As if the artistically liberalized, proudly fantastical way Oates imagined Norma Jeane's life wasn't enough to stir the pot, "Blonde" makes a series of abrasive, potentially off-putting decisions in the way that it brings that story to the screen, largely reducing it to a mournful Passion of the Christ by way of Old Hollywood, with Monroe as the martyr who suffered for all of America's sins.

It's a concept that gets claustrophobic at points, and it's up to each viewer to determine whether that's a good or bad thing. On a pure craft level, at least, "Blonde" is frequently astonishing, starting with the many actors who clock into Norma's stations of the cross. Here, we've attempted to rank those actors' performances — with the caveat that all of them are, at a minimum, good.

11. Dan Butler as I. E. Shinn

"Blonde" is filled with men who abuse Norma Jeane: Men who beat her, men who rape her, men who drug her, men who put her through years of psychological torture, and men who force her to get abortions. And then there's I. E. Shinn, Norma Jeane's agent, who abuses her by providing service, offering up a reassuring smile, and then being utterly indifferent to her suffering.

The cheerful normality with which Shinn leads her into being sexually exploited at the hands of "Mr. Z" is icky enough, but then he keeps one-upping himself, openly belittling her request to re-do an audition (while pretending to support her), ignoring her concerns about her career, and screwing her over financially. He's the embodiment of all the harm done to Norma by the film industry, hiding under the guise of adulation.

You'd be excused for not picking up on the character's importance to "Blonde" on a first go-round, given that Shinn only shows up physically in three scenes, with two additional appearances via phone call. Every time that he appears, however, Dan Butler makes his small role count, fully committing to a weaselly performance-within-a-performance that never drops below the level of acceptable patriarchal manhandling. It's very small but quite solid work.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

10. Evan Williams as Eddy Robinson Jr.

Every relationship of a romantic or sexual nature that Norma Jeane has in "Blonde" turns out to be exploitative in some way. Many of those relationships are, indeed, nothing but exploitative — part and parcel with the cavalcade of endless misery the film puts Norma through. But there are also those relationships that give her, and us, some hope of respite, only for it to be snatched away, making the sting that much harder in the end. In "Blonde," Norma isn't just denied happiness; she is repeatedly made to mourn it.

Norma's relationship with Cass Chaplin and Eddy Robinson Jr., for example, appears to toe the line between exploitation and bliss, only for later scenes to make the case that she's actually having just as much fun as the boys. The lingering source of tension in those scenes is Eddy, whose connection to Norma isn't explored very deeply, rendering him as a sort of mystery. What does he want? How does he feel about their arrangement? What is Norma to him?

Evan Williams plays Eddy so that those questions are never answered, and his wry, ever-so-slightly bitter smile suggests that he has a harder time than Cass getting over his existential hang-ups. When the boys show their true colors, Eddy's betrayal is both more and less shocking than Cass'; his opacity is striking, but somewhat frustrating from a narrative standpoint.

9. Sara Paxton as Miss Flynn

No one but Norma stays in "Blonde" for long; her life is made up of transient connections and fragmented memories. The film makes it so that we, like her, need to scramble for something to grasp on to, something to give shape to the shifting sands of her life. Like Norma, it's particularly easy for us to become attached to Miss Flynn, the neighbor who takes her in and cares for her after her mother proves unfit to do so. She enters the movie like a beam of light, a glimmer of the love Norma has long lived without. And then she exits just as swiftly, sending Norma down the next curves of her twisted path.

Every actor in the movie has the challenge of making a strong impression with a limited number of scenes, but few cast members make as much of an impact with their brief screen time as Sara Paxton. When we first see her, she's de-emphasized as Norma darts desperately into her house to escape Gladys. Only after Miss Flynn has had a chance to calm Norma down do we register her as the nurturing, calming presence that she is. One gets the sense, through Paxton's performance, that Miss Flynn genuinely wishes she could do more for Norma. The pain, guilt, and exasperation that flash across her face as they part ways feel achingly real and irreconcilable.

8. Bobby Cannavale as Ex-Athlete

Given how violently Norma Jeane gets jerked around by the patriarchy, it stands to reason that her efforts to find stability should be marred by chauvinistic violence. Out of all of Norma's partners in the film, Joe DiMaggio — referred to as "Ex-Athlete" in the film's credits, as in the novel — is the one who makes the most concentrated effort to "protect" Marilyn Monroe, and also the one who's most directly and aggressively abusive towards her. Such is the hand that Norma has been dealt in life.

Bobby Cannavale is no stranger to playing charming scumbags, as demonstrated by diverse projects like "Boardwalk Empire," "Spy," and "Homecoming." In that sense, the role of Ex-Athlete finds him in his element; Cannavale nails both the gallantry and sense of security in DiMaggio's early interactions with Norma, and the destructive rage and jealousy that ultimately make him yet another calvary in her life. If there's anything that makes him less memorable than the other men in Norma's orbit, it's that DiMaggio, despite how much of a presence he is both in terms of screen time and plot, is a bit of a one-note figure. There's not much more to him than the man-of-the-house routine, with its inevitable possessive disenchantment. Cannavale is a great performer, but there isn't a lot for him to sink his teeth into.

If you or someone you know is dealing with domestic abuse, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.

7. Caspar Phillipson as The President

"Blonde" doesn't actually come out and say that the U.S. president Norma Jeane becomes involved with is John F. Kennedy. Not only is the character never referred to by name — Caspar Phillipson is credited only as The President — but their encounter is so impersonal that it could have been just about anyone. But, of course, we know that the "president" in Marilyn Monroe's story is Kennedy, and "Blonde" makes no attempt to hide it, either. In a way, this the most subversive direction the film could have taken its depiction of Kennedy. The JFK in "Blonde" is every bit as cruel, predatory, and just plain creepy as any other man in the movie's conga line of monsters. He's not some uniquely Machiavellian villain; he's just like all the others.

Kennedy shows up in a single scene, but it's a searingly upsetting one in which he forces himself upon Norma with the cavalier casualness that only the status of "most powerful man in the world" could permit. Phillipson, the Kennedy look-alike who previously played the 35th president in "Jackie" and on History Channel's "Project Blue Book," delivers his most chilling take on the character yet — a dead-eyed void of humanity, scruples, feelings, or anything, really. His performance makes the film's strongest and most direct case for Norma's status as a victim of American myth-making.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

6. Toby Huss as Whitey

The best scene in "Blonde" is the one that reverses the polarity. The vast majority of the film depicts Norma Jeane as a perpetual sufferer, a woman for whom even the lighthearted comic charms of the greatest Marilyn Monroe performances came at a great emotional cost. At one point, however, we see Norma in her dressing room, accompanied by her team, trading banter and listening to fan mail. In that moment, she's happy, snarky, and self-aware; it's a brief glimpse of the quick-witted, endlessly charismatic comic genius the real Monroe was known to be. In that moment, she's also being teased by her personal makeup artist, Allan "Whitey" Snyder, who effortlessly makes her laugh like only an old, trusted friend can.

Every scene with Whitey in the film carves out a similarly blissful space amidst the Passion of Marilyn. He's the only man in Norma's life who truly sees, understands, and respects her, warts and all. He's the one who holds her hand through breakdowns and laughs with her when she's recovering from drunken dazes. Toby Huss' performance is unshowy, much like Whitey's support for Ms. Monroe. But it's also just about perfect. The warmth he exudes is almost alarming; I kept expecting the other shoe to drop, but it didn't. Watch for the details whenever Huss is in the background of a big scene — his constant attention to Norma, and his instinctive responses to how she feels. It's impeccable character building.

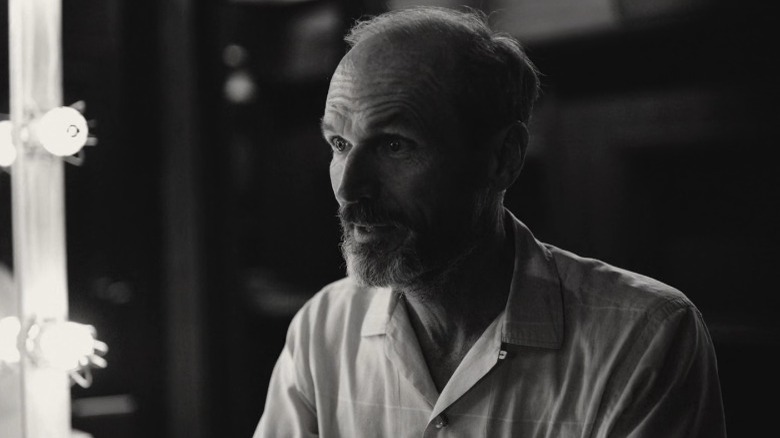

5. Adrien Brody as The Playwright

Even though "Blonde" could be credibly accused of underestimating Marilyn Monroe — let a woman be in charge of her artistry, Andrew Dominik! — the movie does go out of its way to depict her as an intelligent, cultured person who deserved to be taken more seriously, specifically by way of her relationship with Arthur Miller, aka The Playwright. The scene in which Miller is floored by Norma Jeane's interpretation of his play is among the best in "Blonde," and the relationship that unfolds from it is arguably the film's most complex.

The movie's Arthur Miller is a soulful, world-weary man who has seen enough to know that he needs to grab happiness when he finds it. Adrien Brody gives an enormous performance in the role, one full of layers that make themselves apparent without having to be obvious. He has a quiet, incorrigible arrogance; a lingering grief hardened into artistic panache; a gentleness that he's actively working for at all times. He loves Norma, he wants to be more for her than others have, he accepts her projections onto him, and he hates her for what she's doing to herself. All that coexists in Brody's chemistry with Ana de Armas, which refreshingly scans like two adults forging an imperfect bond, as opposed to a flat victim-villain dynamic. It's rich enough work that, by the time that Miller has unceremoniously vanished from the film, we can infer what might have happened between them based solely on what we've seen.

4. Lily Fisher as Young Norma Jeane

Besides Norma Jeane, the character who appears most prominently in "Blonde" is ... Norma Jeane, but as a seven-year-old girl. Like most children, pint-sized Norma is sensitive, observant, and a lot more aware of what's going on around her than others assume she is. The mistreatment she suffers at the hands of her mother, Gladys, manifests most clearly not in the behaviors of Gladys herself, but in Norma Jeane's anguished, powerless, and increasingly desperate reactions. We feel every pang alongside her, and the experiences of young Norma become a map to the woman eventually known as Marilyn Monroe.

Getting that much pain and trauma across without falling into rote repetition is no small job, especially for a child actor, but Lily Fisher aces it. Seven-year-old Norma is never just one thing — she loves her mother and longs for her affection, but also recoils at the sheer absurdity of the things Gladys puts her through; she puts on a brave face as children from abusive households often do, but the pain and confusion always simmer underneath it; she's sweet and innocent, but asks questions with enough clear-eyed authority to stun adults. Most of all, she feels it all so, so deeply. Fisher allows Norma's feelings to come through on her face with haunting, undeniable clarity; her close-ups are almost difficult to watch.

3. Xavier Samuel as Cass Chaplin

Who exactly is Cass Chaplin? It may be because of the lack of an answer to that question that the film's playboy douchebag has fallen into his ways. It's hard to understand what he expects from Norma Jeane, what he's getting out of their relationship, whether he really loves her at any point, and whether he actually sees her like he says he does. There's no telling if Cass is an irresistible love guru with a poet's soul, or the exploitative, gratuitously cruel antagonist his later actions reveal him to be. Maybe, at different points in his life, he's both. Who's to say?

Xavier Samuel's performance doesn't give the game away, and therein lies its power. Cass has his own tragedy to work out, to be sure, and the shame and regret of a life lived under his father's shadow is intelligible in Samuel's every languid intonation. But the logic of it, the mystery of how and why Cass presents himself to Norma the way he does, remains intangible. Each of Samuel's rhapsodic monologues, delivered with eyes trained on the camera, has a gravitational pull of its own. It's the very definition of a star turn, doubly heartbreaking because of how effective it is as a performance that Cass is giving to Norma.

2. Julianne Nicholson as Gladys

Few movie characters in recent memory have been mass centers of omnidirectional pain to a more upsetting degree than Gladys. She suffers and dishes out suffering with the intensity of a tragic figure in a particularly mean melodrama — one of those shocking, blazing Sirkian figures that us viewers are unsure of what to do with. "Blonde" implicitly argues that Gladys is but one of who-knows-how-many women on the outskirts of Los Angeles who's driven to ruin by their proximity to, and ultimate exclusion from, the glamor of Hollywood life, but that's not to say it positions her as a mere allegory. Everything about Gladys and her relationship to Norma Jeane is searingly specific.

Julianne Nicholson has always been a fearless actress, but "Blonde" finds her reaching for new depths of naked, unglamorized human horror. The character is excessive and Nicholson plays her as such, never holding back during any of Gladys' outbursts or tempering the uncontrollable anger she feels towards her own daughter. At the same time, she makes Gladys' own victimhood plain, adding nuance to her mostly unsuccessful efforts to be a decent mother. This dizzying feat of muscular yet perfectly controlled acting is only made more impressive by the scenes in which Gladys reappears in a nursing home. She's a shell of her former self, unassailable to Norma yet every bit as capable of dealing existential damage.

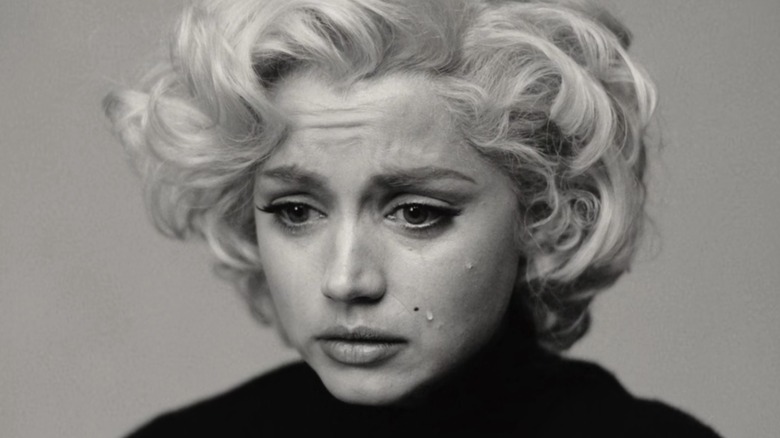

1. Ana de Armas as Norma Jeane

"Blonde" doesn't piece Norma Jeane together; it leaves the pieces on the floor, and leaves us to assemble them on our own. The film technically conforms to the narrative boundaries of a conventional biopic, but offers so little connective tissue between the big moments that "Marilyn Monroe" remains no less of an enigma by the end of its run time. One can take issue with the pieces Andrew Dominik chooses for his puzzle; many have argued that the movie focuses too much on moments of suffering, as though Norma Jeane's existence were nothing but a series of those.

I will say that it's hard not to get a little up in arms about the borderline perverse decision to cast the perfect actress as Marilyn Monroe, have her painstakingly refine her performance, and then make her spend all of her time hitting the same two or three emotional notes over and over. But the indignation spurred by that decision is only a testament to Ana de Armas' work. In the few moments where she does get to show more sides of Norma — such as the aforementioned dressing room scene — she is breathtakingly, astonishingly perfect. Whatever limits there may be to the representation of Norma Jeane in "Blonde," they're certainly not de Armas' fault; she fights tooth and nail to honor the woman in her totality.