15 Movies Like Heat That Are Definitely Worth Watching

When director Michael Mann was cutting the iconic downtown LA shootout for his blue-hued 1995 neo-noir masterpiece "Heat," he initially set the scene to a foley mix of faux gunfire. But it just wasn't right. He swapped out the track for sound captured on location. "We shot with full-load blanks," the auteur told Vulture. "We were in these glass and steel canyons and the gunfire reverberated in a certain real way, so they had an authenticity to the place that really was unique."

Mann has claimed to "reject realism," but it's that close attention to detail, merged with his overall expressionistic brilliance, that turned "Heat" into a genre of its own. "Heat" isn't just a heist movie — it's the heist movie. It's the platonic ideal on which all other modern films about clever crews of crooks and the cops who chase them are based.

But "Heat" is also a mood, more than a neo-noir both aesthetically and tonally. Robert De Niro's bank robber never unfurls any silly schematics. Al Pacino's jittery major crimes detective (who Pacino himself says he was playing as if high on cocaine) never utters a word of narration. There are no tedious expository characters. A lot of the dialogue — particularly from Jon Voigt's fence — is barely even audible. Absent too are irritating tech-related cliches: holograms, touch screens, the wacky hacker in a van doing a digital deus ex machina, and so on. "Heat" is a completely convincing simulacrum of high-end crime, but one with painterly chiaroscuro style to spare. Here are 15 films in that same spirit.

Collateral (2004)

"Collateral" isn't just worth watching, it's worth re-watching, as Michael Mann's second-best film delivers much of his indelible style, with some notable new wrinkles. "Collateral" is smaller and less ponderous than "Heat," mostly taking place around the claustrophobic cab of an aspiring limousine entrepreneur played by the excellent Jamie Fox. The film's suspense is carried by a menacing backseat driver, a typically intense Tom Cruise playing against type as a grey-haired, cold-blooded contract killer who enlists Foxx, against his will, for a one-night rampage through L.A.

"Collateral" is not a heist movie, and it is decidedly from the portion of Michael Mann's canon where he got very into adding Audioslave songs to his soundtracks. The film still works. In fact, it more than works, and contains tons of the director's signature middle-stage flair. This includes the then-novel use of mixing old-fashioned film stock with first-generation digital cameras that, frankly, weren't that capable in 2004. But the intermittent digital grain, with the attendant soap-opera-style frame rate, gives key scenes an unsettling sense of lo-fi voyeurism.

After "Heat," Mann became more interested in cinéma vérité, a less stately style with more handheld shots and disorienting wide-lens close-ups. That change is also very noticeable in his other great film, 1999's "The Insider." And, as always, Mann is again the master of painting a dark yet freshly striking vision of the high-level crime that he imagines unfolds in Los Angeles just after the sun goes down.

Ronin (1998)

John Frankenheimer's "Ronin" might be the closest analogue to "Heat" in that it's a competent caper film and stars Robert De Niro as a hard-boiled thief extraordinaire. Bobby D. plays Sam, a former intelligence officer who uses his spycraft for ill but is unable to shake a classically American sense of honor, even as he's plotting an international crime with a newly assembled team of crooks.

And that's what makes Sam worth rooting for. The film's opening credits explain that a ronin is a "samurai whose liege was killed." These wayward warriors are thus forced to wander the land as "hired swords." "Ronin" is certainly saying something about a crumbling American empire whose soldiers have lost their purpose, but not their knightley sense of duty. Isn't that the formula for a great anti-hero?

Of course, given the film's spy-inspired plot, there's plenty of double-crossing, and De Niro's Sam is so quietly cool under pressure that he's easy to root for even without the mild political subtext. Upon the release of "Ronin" in 1998, critics weren't wild about it. The Washington Post called it, "a disappointingly conventional thriller ... whose pretensions of exoticness are ultimately thwarted by a nagging mistrust of its audience's sophistication." "Ronin" does lack the stylistic panache of Michael Mann's masterwork, but Frankenheimer's less arty approach also lets the plot wash over you unencumbered. No heist film is going to rival "Heat." You'll be chasing that dragon for the rest of your days. "Ronin" at least gives you a taste.

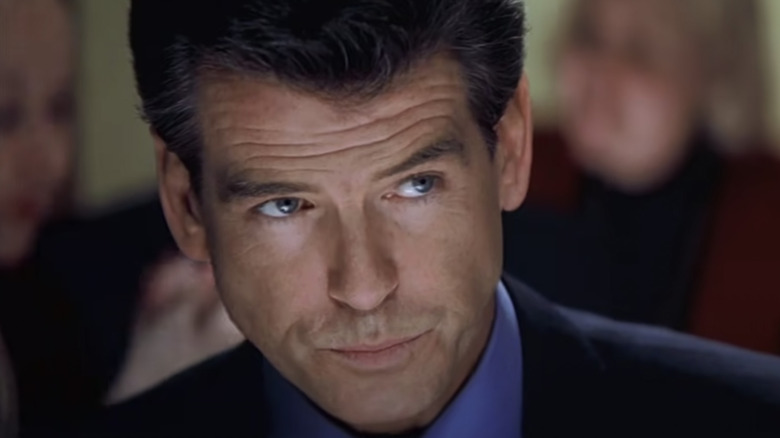

The Thomas Crown Affair (1999)

"The Thomas Crown Affair" is a lot more fanciful than the gritty "Heat." After all, it stars the smirkingly handsome and irrepressibly dashing Pierce Brosnan as the titular character in this 1999 remake of the 1968 original. Brosnan is tremendous playing an independently wealthy English gentleman who steals high-end art just for kicks. He's basically rehashing that bourgeois charm that made him such a compelling James Bond, so even though the spiffy flick has been called a neo-noir, there's nothing too dark about this jaunty big-budget delight.

"The Thomas Crown Affair" is really more interested in clever plot mechanics than moody stylishness, but the maze is so well constructed that it still lets you believe all this high-wire heist stuff is actually possible. The movie also has a compelling romantic plot as Rene Russo tries to pin Crown down in more ways than one. But it's apparently not so easy to catch a crook who loves high art almost as much as he loves to steal it.

Tommy Crown is a Robin Hood figure, and his only partially concealed passion for toying with the world that curates priceless oil paintings is infectious. The only thing truly criminal about this film is how underrated it is, at least according to its merely solid critics' aggregate. These C to C+ scores really fail to reflect how fun it is to spend two hours with Brosnan when he's up to no good.

The Town (2010)

In 2010, Ben Affleck decided he would just remake "Heat" and call it "The Town." Los Angeles becomes Boston, Affleck becomes a sportier version of Robert's De Niro's Neil McCauley, and Jon Hamm plays an FBI good guy as a somewhat relaxed imitation of Al Pacino's manic detective Vincent Hanna.

The film works best if you haven't seen "Heat," argues MTV News critic Laremy Legel in an otherwise friendly review. Jeremy Renner is the film's loose cannon and a total standout. He plays Affleck's hair-trigger ride-or-die bestie, who Ben's bank robber can always count on to have his back, if not to keep things quiet. Renner is sort of taking the Waingro role here. He's loyal, yet similarly sociopathic, and so represents the fly in the ointment that could muck up even the best-laid plans for a Beantown bank job.

Audiences liked "The Town." Critics mostly did, too. Mann already perfected the form, and imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, so leave "Heat" behind when you pop on this flick and give Boston's own big Ben some credit. Not only did Affleck direct this film, he also penned the script, along with Aaron Stockard and Peter Craig. To the trio's immense credit, the plot is piano-wire taut and has the kind of satisfying ending that, much like the perfect crime, is only possible when no loose ends are left behind.

Casino (1995)

"Casino" is a heist film in the sense that it delves deep into the way the mob once made its millions. Also, it stars Robert De Niro as Sam "Ace" Rothstein, a mobbed-up Jewish gambler who once again treats his vocation with incomparable professionalism — at least until the pressure cooks him. "Season after season, the prick was the only guaranteed winner I ever knew," explains Joe Pesci's brutal Cosa-nostra enforcer, Nicki Santoro, "but he was so serious about it all I don't think he ever enjoyed himself."

It's Scorsese's fidelity to explaining the actual inner workings of mob economics that puts this film on par with "Heat." "Casino" is a real how-to for running a crooked casino business. Perfectly pitched narration from key characters explains the scam down to the silk-tied Sicilians skimming the take from inside Sin City cash rooms.

Most of all, "Casino" is Scorsese's apex achievement as an artist. Sure, "Goodfellas" will always get that "The Godfather" grace over at the AFI 100. It came first, and given the overlap of Joe Pesci playing an identical psychopath in both, it will be derided in some quarters as a sort of lesser sequel. Reject these notions. Just as Michael Mann peaked with "Heat," "Casino" is the movie where Scorsese put it all together: the gilded glow of the down-lit cinematography, the innovative editing, a superfluous script, and pitch-perfect performances. This is the auteur's most self-actualized work at the helm of a great Hollywood film.

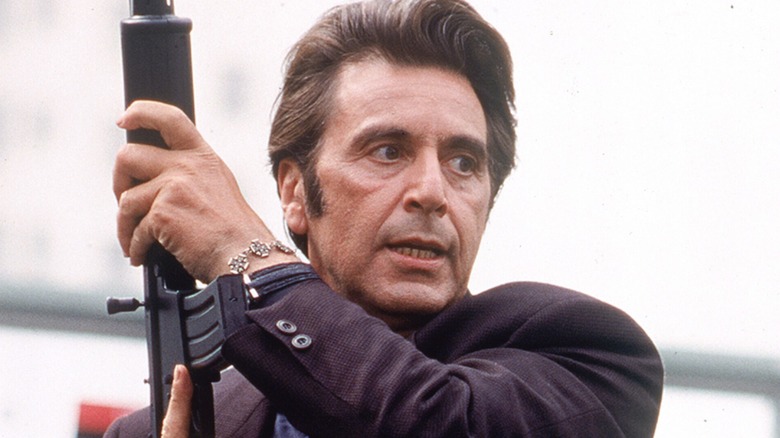

Carlito's Way (1993)

Brian De Palma has always been the eccentric rogue among his more famous squad of friends: Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and Francis Ford Coppola. Maybe as a result, he's had fewer hits than his peers, and there are no Oscars inscribed with his name. Yet, at his best, he may be the group's alpha. "I'm not part of any establishment," De Palma defiantly declared in the eponymous 2015 documentary "De Palma."

Unlike Marty (as his familiars call him), De Palma stans need not start a Scorsese-style dispute about which work is his ultimate achievement. "Carlito's Way" is right next to "Heat" on the list of the all-time most rewatchable movies, a gritty crime noir that checks all this manly genre's boxes. The director himself has acknowledged that this is his masterpiece. After the film opened in Berlin, some critics dismissed the film as standard gangster fare. De Palma disagreed. As he says in "De Palma," "I don't think I can make a better picture than this."

Like "Heat," "Carlito's Way" also stars the chameleonic Al Pacino, this time playing a Puerto Rican ex-con just paroled thanks to his crooked, coked-up lawyer, brilliantly embodied by Sean Penn in a frizzy wig with a fake receding hairline. All Carlito wants is to go straight, win back his ex, and literally sail into the sunset. But as Pacino himself so famously said in "The Godfather Part III," "Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in!"

The Usual Suspects (1995)

Bryan Singer's "The Usual Suspects" felt revolutionary in 1995. This virtuosic and mesmerizing modern noir is flawless front to back, then kicks you in the teeth with a twist that made the film more meme than movie. The plot is so air-tight that it's a wonder that the perfectly imagined characters didn't suffocate — it was almost a given when writer Christopher McQuarrie picked up the Academy Award for best original screenplay.

The script's hook is a terrifying bedtime story for underworld goons about a crime boss so mythic that the mere mention of his name turns hardened criminals into blubbering wretches. Then, Singer sprinkles on style with the finesse of Salt Bae standing over a sturgeon. The suspects' dreamlike aura quickly takes away your equilibrium, setting you up perfectly for that sucker-punch finish. Kevin Spacey also justifiably took home an Oscar in 1996 for his cat and mouse games in the brilliant scenes he shares with Chazz Palminteri's lead detective.

If you haven't revisited "The Usual Suspects" recently (and, given the allegations against both Singer and Spacey, that would be understandable), try to think of the last time you saw a visually jaw-dropping film that didn't rely on a graphic novel as a storyboard. Though Singer imbues the violence with gravity — despite a psychopathic Stephen Baldwin cracking wise — he can't help but beautify the bloodshed. "The Usual Suspects" might be the modern noir "Heat" fans will most admire.

Training Day (2001)

Michael Mann's films are nothing if not manly. At its core, "Heat," like "Collateral," is about a battle of wills between two very cool dudes. That's also the beating heart of "Training Day," and Denzel Washington and Ethan Hawke are more than up to the task in this good cop-bad cop standoff.

"Training Day" is the creation of another serious L.A.-ologist, writer David Ayer, also responsible for the verité excellence of 2012's "End of Watch." That film might even merit an honorable mention here had Ayer, that time serving as director as well, not opted for the whole shaky-cam "Cops" aesthetic.

Ayer earns his auteur status in the fullness of his vision of L.A. The Illinois native's bloody take on the City of Angels is more diverse than Mann's, and more sinister, too. He's not just interested in high-line prowls, but lowly street toughs. Ayer's L.A. is basically overflowing with cartel-connected killers and neighborhoods so neglected that even the police dare not enter. That leaves a lot of room for anti-heroes to run wild.

In some ways, this whole "Heat" genre is more western than noir. "Training Day" perfectly puts this in perspective. Pistols are replaced with Glocks, horses with American-made gas guzzlers. "Training Day" is the fantasy of a sprawling urban wilderness so utterly untamed that one man must take the law into his own hands.

Drive (2011)

Nicolas Winding Refn's "Drive" is another neo-noir masterpiece that replaces the logistical realism of "Heat" with a more lyrical version of organized criminal violence. But unlike Michael Mann's film, with its somewhat underdeveloped love stories, "Drive" is probably the most openly romantic film in this genre.

Ryan Gosling plays a part-time Hollywood stuntman who moonlights as a getaway driver for crooks who don't want to be left in the lurch. He's like Uber Black for bank robbers, minus the aux cord and box of mints. In quite the noir-genre reversal, especially considering the motor-mouthed heroes who pioneered the genre, Gosling's character is so tight-lipped that he doesn't even have a name — the credits simply refer to him as "Driver."

Neo-noir heroes aren't at all like the blab-happy city slickers of noirs past. Gosling courts co-star Carey Mulligan's soulful single mother amidst a backdrop of absolute mayhem. The actors even collaborated on cutting their own lines to better set the mood for this laconic love affair. "We would sort of sit around in the morning and Nic would say, 'Do you want to say this?' And I would say, 'No.'" Mulligan told Uproxx. "And Ryan would go, 'I don't wanna say that.' So we'd end up with four words..." Gosling added at a junket in 2011, "I don't think you need all this talking in movies. Sometimes, it's easier to get the point across if you're not saying something. The audience is smart. They can see how somebody feels."

Hell or High Water (2016)

The only real difference between a neo-noir like Michael Mann's "Heat" and an "anti-western" like "Hell or High Water" is like the difference between Taylor Swift the pop star and Taylor Swift the country star: One wears cowboy boots. Modern westerns are mostly just noirs with a twang, but director David Mackenzie's excellent anti-western two-steps into territory "Heat" and its imitators don't broach: politics.

"Hell or High Water" is, blessedly, an original screenplay. It sprang from the mind of Texas native and actor-writer Taylor Sheridan, who also penned "Sicario." The scribe says he sees these films as part of a trilogy about "the modern-day American frontier." As he told IndieWire, "I was exploring the death of a way of life, and the acute consequences of the mortgage crisis in East Texas."

The film came out in 2016, but Sheridan obviously had the 2007-2008 financial crisis on his mind. For a refresher, that was when big banks gave out so many home loans that, after ordinary folks got buried under their own bad bets, a crooked derivatives market built atop this house of cards toppled the global economy. Against that larger context, Chris Pine and Ben Foster play brothers trying to even the odds and save the family farm by knocking off those purportedly predatory banks. Jeff Bridges plays the old-salt sheriff tasked to stop them. Even though this film is overtly political, it sticks with the "Heat" genre's most humanist convention: You root for everybody, no matter what color hat they wear.

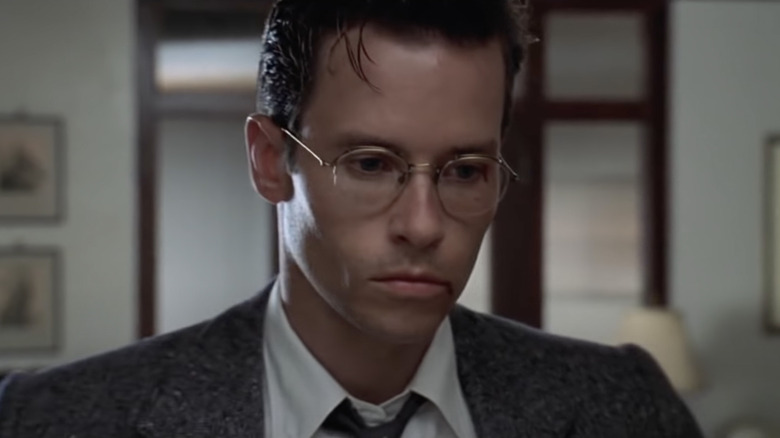

L.A. Confidential (1997)

If you like a hard-boiled detective story with a sprawling ensemble of legendary Hollywood actors and a twisty L.A.-based crime plot, you might also vibe with this modern-era movie posing as a noir from Tinseltown's golden age of flatfoots and private dicks.

One of the hallmarks of classic noirs is how hard they are to actually follow. In the '40s films that gave birth to noir, like "The Big Sleep" or "The Maltese Falcon," Humphrey Bogart talks so fast, and so often says the opposite of what he means, that it's a bit much to keep up with. The stumble of the more static filmmaking of that era — and of "The Maltese Falcon" in particular — is that Bogie uncovers a slew of non-visual clues in quick succession, making it hard to keep the parade of characters straight and reducing cinema to a puzzle. As Alfred Hitchcock famously (and derisively) explained, this kind of plot-clotted movie is an emotionless — and thus boring — "intellectual process" instead of an emotional one.

Many highfalutin lists of Hollywood's greatest films claim that Roman Polanski's 1973 classic "Chinatown" is the go-to neo-noir about corruption running through 1930s Los Angeles. More populist lists endorse "L.A. Confidential," which depicts an equally corrupt City of Angels 20 years later. Critics correctly concur. The Washington Post called it, "roundly entertaining." The New York Times dubbed it a "resplendently wicked ... tough, gorgeous, vastly entertaining throwback to the Hollywood that did things right."

The Dark Knight (2008)

It's not like you haven't seen this film, but many Batman fans don't realize that "The Dark Knight" and its realistic and gritty take on the Caped Crusader isn't conceivable without "Heat" as an inspiration — at least according to director Christopher Nolan.

Following the success of "Batman Begins," Nolan wanted to expand the scope of his DC universe for the sequel. The problem was that, budget-wise, he'd already gone all in. He needed artistic inspiration for how to build out Gotham. "One of the biggest epic films I have ever seen is Michael Mann's 'Heat,'" the action auteur said during an interview for the book "The Nolan Variations" (via No Film School). He went on to explain, "That is a true Los Angeles story, just wall-to-wall within the city. Okay, we'll make it a city story."

Nolan even screened "Heat" for the "Dark Knight" department heads before shooting. "I always felt 'Heat' to be a remarkable demonstration of how you can create a vast universe within one city and balance a very large number of characters and their emotional journeys in an effective manner," he said. Nolan's "The Dark Knight" is full of indelible images of Chicago (standing in for Gotham) thanks to director of photography Wally Pfister, but "Heat" was always the duo's architectural muse. As Nolan explained to GQ, Mann simply understands the "grandeur of a city and how it can become a kind of epic playground."

To Live and Die in L.A. (1985)

If "Heat" is missing one thing –- and truly only one thing –- it's Willem Dafoe. All films without Willem Dafoe are missing Willem Dafoe, but "To Live and Die in L.A." is not one of those films. Dafoe portrays Rick Masters, a master money launderer who is hotly pursued by Los Angeles Secret Service officer Richard Chance (William Petersen) for killing his partner. If you're looking for a similar cat-and-mouse chase anchored by two solid performances, this will scratch your itch. Dafoe is effortlessly menacing as Masters, while Petersen is so brash that he makes Vincent Hanna look like Judy Hopps (in a good way).

The film, directed by the late William Friedkin ("The French Connection"), is a far cry from "Heat" in terms of style. It was released in the heart of the '80s, punched up by a pulsating electronic score from the band Wang Chung and filled with enough unintentionally hilarious one-liners to fill an IMDb Quotes page. However, it's just as intense a crime thriller, if not more so. What "Live and Die" lacks in bank heists it makes up for with its central car chase, which may hold the record for a single scene with the most driving into oncoming traffic. Chance, alongside new partner John Wukovich (John Pankow), gets into his revenge spiral so deep that any way out is bound to be dirty, and the results will genuinely shock you. The film's final stand-off may not be as patient as "Heat," but it sure will stay with you.

L.A. Takedown (1989)

Before "Heat" became "Heat," it was "L.A. Takedown." In the late '70s, Michael Mann wrote his first draft of the film as a 180-page screenplay. However, he struggled to get it produced. When NBC called looking for a new series, Mann slashed 70 pages, raised funds, and filmed the script as a television pilot. Though the network never picked it up, the film remains a rare and fascinating case study in second chances. "L.A. Takedown" is a perfectly serviceable crime thriller, but it's especially worth watching to appreciate how a number of key aspects make "Heat" a far superior version of the same story.

For one, you have two different stars. Though Scott Plank as Vincent Hanna does exert a brazen confidence reminiscent of Al Pacino, Alex McArthur as Patrick McLaren –- a stand-in for Neil McCauley -– is no Robert De Niro. The New York-born duo inhabit their characters with far more nuance than Plank and McArthur and Mann's condensed script leaves far less time devoted to the two actually interacting, leaving the film's central relationship a bit flat.

Not only is the story compacted, but the entire film feels rushed. Shot over the course of 19 days and clearly on a limited budget, Mann simply didn't have time for polish. Shot in limited locations with a run-and-gun pace, "L.A. Takedown" lacks the sense of atmosphere that is present in "Heat" from the jump. Watching one of the many side-by-side comparisons posted on YouTube, the difference is night and day.

Ambulance (2022)

Michael Bay may get a lot of flack, but he knew what he was doing with "Ambulance." The film's inciting bank heist is incredibly "Heat"-coded: a jacked-up Jake Gyllenhaal channeling Pacino, a crew of wise-cracking assailants, and a rampant shootout on the streets of Los Angeles that leaves their driver in the dust. However, while Mann keeps his climax centralized, Bay widens his scope to include medical personnel, which leads to the film's eponymous getaway vehicle. As robbers Danny (Gyllenhaal) and Will (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) are pursued from all corners, Bay takes a Mann-esque tension and sustains it for his entire running time, which makes it enough to recommend for anyone looking for their "Heat" fix.

Now, of course, Michael Bay is no Michael Mann. The L.A.-born filmmaker still feels the need to overcompensate much of his action, this time with an overabundance of staged car destruction and high-flying drone photography, both of which go from simply vapid to ridiculously excessive and distracting. However, without the CGI flair of his "Transformers" films, Bay gets to keep his focus on the ground. The impressive in-vehicle cinematography never feels too claustrophobic and the stunt work during the film's several intermittent car chases is clearly an achievement. These chases have the characters swerving in and around L.A.'s highways and backstreets, making the city its own character in the film. It's a locale pulsating with life –- and law enforcement -– in a way any "Heat" fan will surely appreciate.