Indiana Jones And The Dial Of Destiny Spoiler Review: A Safer, Less Exciting Indy

The specter of 21st-century movies featuring the intrepid adventurer and archeologist Indiana Jones has raised the question: what is an "Indiana Jones" movie without Harrison Ford? The end of the 2008 film "Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" was a playful tease regarding whether or not Indy's long-lost son Mutt Williams (Shia LaBeouf) would be the next Indy-style hero, taking on the mantle and literally about to wear Indy's fabled fedora before our hero snatches it up and walks off into the sunset with his now-bride Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen). Indy was getting on in years then, and even more so when we meet him in the fifth (and supposedly final) entry, "Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny." Here, too, the question is asked, but within the film itself: what is the world without Indiana Jones? Unfortunately, "Dial of Destiny" winds up asking another question and comes up somewhat short: what is an "Indiana Jones" movie without Steven Spielberg?

Now, it's true that Spielberg is a credited executive producer, and no doubt had some level of insight and feedback to share with the man who took over behind the director's chair, James Mangold. And it's equally true that Mangold is no stranger to working with iconic characters, as in the 2017 film "Logan" with the mutant Wolverine, and that his filmography is littered with solidly entertaining fare, such as "Logan," "3:10 to Yuma," and the recent "Ford v. Ferrari." Yet as enjoyable as those films are, and as generally capable as he is, it's just extremely difficult to measure up to Spielberg's shadow. As unfair as it may seem to compare the two directors, "Dial of Destiny" is not often shy about recalling the past. Though Ford is the only actor to have a truly substantial returning role — John Rhys-Davies returns as Indy's faithful friend Sallah, but only for about 5 minutes — the past weighs heavy on the events of this film. (The script, credited to four writers, makes explicit references to previous entries in the series, as when Indy bitterly recalls having to drink the blood of Kali in "Temple of Doom".)

The film opens with an extended prologue set in Indy's past; this time, unlike the opening of "The Last Crusade," we're not watching a younger actor playing Indy, but a de-aged Harrison Ford himself. The upshot of the opening, set in 1944, is that Indy and fellow archeologist Basil Shaw (Toby Jones) are trying to wrest away a couple of valuable trinkets from the Nazis, with an ensuing nighttime battle culminating on the top of a moving train. But to accomplish the various mini-setpieces within the larger section, we have to see a younger version of Ford through the same type of CGI that's brought back to life young versions of Carrie Fisher in "Rogue One" and Michael Douglas in "Ant-Man." The difference is how much more time we get with the younger Ford, an effect that sometimes approaches being convincing, but often falls on the wrong side of that balance. The fact that so much of the opening fight is set at night speaks to the sense that these effects are shaky — it's easier not to see the virtual seams if the lighting's not great. (The other thing that sinks this effect: as much as Ford may look younger here, his voice sounds the same throughout the entire film, as opposed to its grizzled edges being audibly softened.)

The future and the past

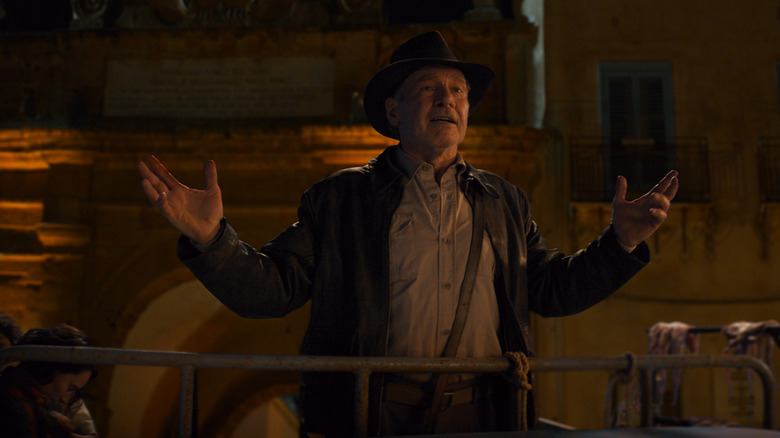

Once the opening stretch is done, we see the current Indy in the summer of 1969, and he's not doing so hot — where once Indy cut a figure of dashing and debonair heroism, he's now a grizzled old man shouting at his youthful hippie neighbors to turn down their rock music. (Because it's "Indiana Jones" and Disney, they were able to spring for "Magical Mystery Tour" as the song being played so loud as to infuriate Indy.) Indy is also wrapping up his final go-round as an archeology professor, now to a few handfuls of students who seem unable to stay awake during his class. It's only a visitor who raises his interest when she's able to answer questions about the life and times of the famed scientist Archimedes. But then, as Indy learns, that visitor ought to know about Archimedes — she's Helena Shaw (Phoebe Waller-Bridge), the daughter of the now-deceased Basil. She's also Indy's god-daughter, though Indy hasn't exactly hung around lately, in favor of keeping to himself after his marriage to Marion hit the rocks (he's got some divorce papers at home he tries to ignore). Helena is the spark that sets the adventure in motion, as she informs Indy that Archimedes' fabled invention the Antikythera needs to be located and procured before the prying hands of ex-Nazi scientist Jurgen Voller (Mads Mikkelsen) gets there first.

The Antikythera is the film's MacGuffin (and also the dial noted in the film's title). And what does it do? Well, Voller believes it's a device whose two halves — when combined — can enable its owner to travel in time. Voller wants very badly to travel back in time 30 years to 1939 so that he can ensure the Nazis will win World War II. (As Voller says in one of the few truly unnerving moments to a hapless hotel porter, the Americans didn't win the war so much as Hitler lost it.) In the post-war environment, Voller has done well by inserting himself into American culture as a professor and as one of the scientists aiding America in the space race to the moon. But his true goals are selfish and evil; he's aided by a couple of toughs, including a trigger-happy American named Klaber (Boyd Holbrook) and a young Black CIA agent (Shaunette Renee Wilson).

It's not that the pieces aren't there for a truly rip-roaring adventure in "Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny." In many ways, it's true that this relatively straightforward film is a less enervating one than "Crystal Skull." None of the film's action sequences are as groan-inducing as the bit in "Crystal Skull" where Mutt Williams swings in and around jungle vines with a series of monkeys, and the film-to-digital shift is less annoying once the film settles into the year 1969. And frankly, compared to so many superhero movies, it's close to a breath of fresh air watching Ford, Waller-Bridge, Mikkelsen, and the others interacting with each other either on location or in sets that don't make it seem like the actors are just a few inches away from greenscreen or bluescreen backgrounds.

A low bar to clear

But those are not immense bounds being leaped, or massive mountains being climbed. That "Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny" is simply not terrible is only a cause for so much celebration. While "Crystal Skull" is — for many of us, at least, its defenders aside — not a high point in Steven Spielberg's career, it's still a film directed by one of the most gifted helmers to have ever graced Hollywood. In the same way that "The Last Crusade" felt somewhat like a corrective to the much darker "Temple of Doom," there's something of a similar feeling to "Dial of Destiny." Both "Crusade" and "Destiny" start with a lengthy prologue at a point earlier in our hero's life; both films re-establish Nazis as the bad guys; and both films attempt to conclude our hero's life in a way that is presumably most satisfying. But the action scenes are generally a little weaker in "Dial of Destiny," either because there is a sense of elasticity instead of tactility in the goings-on or because the staging and choreography feel a little flatter.

The most interesting aspects of "Dial of Destiny" are those that seem to quote its predecessors, either intentionally or not. Much of the arc for Helena, whose intentions are quickly revealed to be less noble than initially presented, mirrors that of Indy in "Temple of Doom." For Helena, it's more exciting to pursue the notions of fortune and glory as opposed to Indy's now-common refrain that certain items belong in a museum. (She, like Indy in "Temple of Doom," has a wisecracking kid sidekick, this one played by Ethann Isidore.) By the end of the film, she's come back to the lighter side, but when we see her barter with Voller over the pieces of the Antikythera, she seems much more willing to be seduced by venality as opposed to selflessness. And Voller — in part because Mikkelsen's character wears glasses — is less a tough-guy thug and more in line with the bespectacled Nazi from "Raiders of the Lost Ark" who winds up with his face melted off in the climax. While it's intriguing to see these new characters as echoes of those Indy's dealt with, or been similar to, in the past, all that does is remind you of how much better the other films in this series truly are.

"Dial of Destiny" does admittedly become legitimately affecting if only because it's surprising in the final act. Earlier in the film, Indy revealed that a large part of why he and Marion went their separate ways is because Mutt enlisted in the Vietnam War and died soon after, and the grief was too much for them to bear. In the climax, he and Helena try and fail to stop Voller from using the Antikythera to travel back in time. But the good news is that Voller's calculations were wrong — though they have traveled in time, they've gone to the historic Siege of Syracuse, which occurred in 213 BC. In the ensuing melee, Voller and his men are killed, and Indy finds himself meeting Archimedes in person, the latter of whom is understandably baffled at the arrival of these outsiders. Indy is all too willing to lie down and accept his presumed fate, choosing to die in the past as opposed to living in the future.

Leaving the hat behind

Whatever else is true of "Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny," it cannot be said that Harrison Ford isn't giving his all. Considering that he's now in his eighties, you have to figure that this really is the last time he's going to play Indiana Jones. (And when you think about his recent filmography, this is likely the last time he's going to play any of the iconic characters that established his stardom in the 1970s and 1980s.) The weight of his past and of this character is evident in how Ford plays the role, no less so than in the finale. Seeing as this is a chapter in a largely upbeat adventure series — and also, y'know, a Disney movie — it's not shocking that Indiana Jones does not die in the past. But it's not because Indy realizes his mistakes or listens to Helena's exhortations that he should come back to his own time; Ford makes the resigned choice quite effective even in a mildly goofy setting.

But again, this is not a movie to end on a downbeat note. Helena takes matters into her own hands, knocking Indy out so that they can return to 1969. And once they do, Indy is brought back to health in his apartment to be greeted once more by the visiting Sallah and Marion herself. The movie concludes with two bits that are moderately effective in their own right — first, Indy and Marion return to their romantic ways by echoing a tender scene from "Raiders" where Marion kisses the only parts of Indy's body that aren't in pain, and second, Indy grabs his fedora off a clothesline right before the credits roll. There's something about the closing scene that showcases the film as a whole, both in what works and what doesn't. Ford and Allen fall right back into their old style, which is nice to see, but the script can't help but give them material that's nudging the audience in the ribs to remember what came before.

Perhaps there was no way that "Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny" was going to feel even as good as the '80s-era films from director Steven Spielberg. As much as Spielberg may be a better action filmmaker than James Mangold, it's not as if the iconic director was able to pull off a great entry with his 2008 film. "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade" ended with our hero literally riding off into the sunset, which would have been more than enough for the character. The book could have closed then. "Dial of Destiny" does not tarnish the reasons why we love Indiana Jones. It reminds us that Harrison Ford is a great actor and that the original films are quite excellent. But that's all it does; it reminds us of the past instead of establishing itself as an appropriate final chapter.