12 Underrated Biopics That You Need To See

The biopic has a long and successful history. Cast a net over the last 60 years and you'll find all manner of enduring works, ranging from "Lawrence of Arabia" and "Bonnie and Clyde" to "Serpico," "Amadeus," and "Schindler's List."

You needn't look back that far, though. The last two decades have seen biographical dramas such as "A Beautiful Mind," "The King's Speech," "12 Years a Slave," and "Green Book" all take home the Oscar for best picture. Then, there are the best actor winners. In the last 10 years, Daniel Day-Lewis, Matthew McConaughey, Eddie Redmayne, Gary Oldman, and Rami Malek have all won Oscars for biographical performances.

However, none of the biopics below won a "big five" Oscar. These films may have earned critical acclaim and even found a small audience, yet they have been left in the rough compared to such films as "The Imitation Game" and "Darkest Hour." Here are 12 underrated biopics that you need to see.

My Friend Dahmer

In 2022, Jeffrey Dahmer became something of a dubious cultural icon with Netflix's curiously titled "Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story." The 10-part miniseries proved to be a skin-crawling experience with strong performances and an unflinching gaze that told a compelling account of the killer that was far superior to earlier projects such as "Dahmer" and the low-budget scuzz-fest"The Secret Life: Jeffrey Dahmer."

However, the hyped Netflix series is not the first successful dramatization of Jeffrey Dahmer's life. That distinction goes to "My Friend Dahmer," the brilliantly understated drama adapted from a graphic novel by John Backderf, who knew Dahmer as a young man. "My Friend Dahmer" focuses on the serial killer's high school years, tracing the roots of his pathology with foreboding dramatic irony. There are no cheap shocks, just a slow-burning tension that leaves you queasily unsure of what's going on in Dahmer's head. We all know where this will lead, and we're looking for the signs everywhere.

Ross Lynch is the anchor of this unnerving story. His performance as Dahmer may be less developed than that of Evan Peters, the brilliant lead of "Monster," but he does a fine job with the narrower focus of this origin story. Lynch's pathos puts the viewer in something of a moral quandary. Dahmer is a troubled young man with no friends and no life, yet our knowledge of his eventual brutality complicates our sympathy and empathy, to say the least.

Christine

"Christine" is about all-consuming anxiety, angst, and depression. This is not an enticing synopsis, but if more people knew the sad, shocking story of Christine Chubbuck, this critically praised but publicly neglected work may get the attention it deserves.

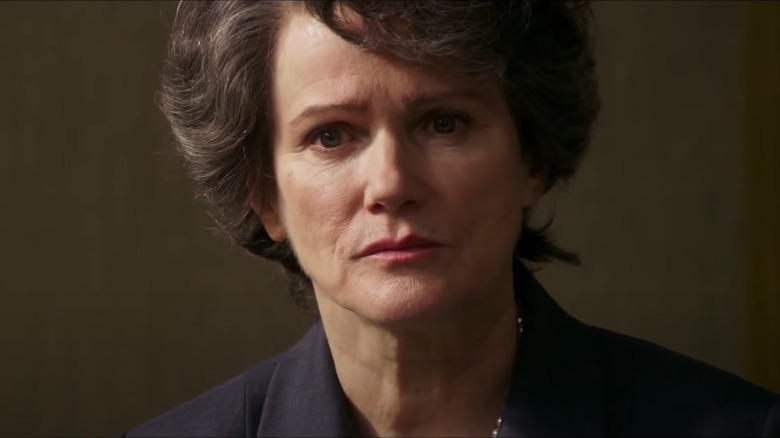

Chubbuck was a television news reporter based in Florida who, after several years of mental health issues, shot herself live on air in July 1974. It is an appropriately bleak story for director Antonio Campos, whose earlier work includes "Afterschool" and "Simon Killer," both of which are dark, brooding films. Campos directs "Christine" with a similar deliberate pace, capturing the slogging burden of Chubbuck's psyche. It is a character study that requires a measured and introspective performance, and Rebecca Hall succeeds.

Hall shows us that Chubbuck was smart and ambitious but also aloof and overly earnest. She was as conscientious as they come, but she scoffed at the station's tabloid nature and clashed with her manager (Tracy Letts), whose editorial guideline was "If it bleeds, it leads." This was at odds with her strident brand of journalism, and it got in her head. Deeper in her head, though, was the presence of George (Michael C. Hall), her colleague and unrequited love interest. Sadly, Chubbuck never found love or intimacy.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt was a philosopher best known for her reaction to the trial of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi bureaucrat who authorized the deportation of approximately 440,000 Jews from Budapest, Hungary. The film, directed by Margarethe von Trotta, focuses on this episode in Arendt's life. It is a story of one woman defying a hive of arrogance and plain lazy thinking in New York City's intellectual circles.

The point of contention was Arendt's impression of Eichmann, who was standing trial in Israel. Unlike both the public and her peers, she did not believe Eichmann to be an evil monster. To Arendt, such a sentiment aggrandized the Nazi figure. Instead, she saw him as merely a bureaucrat and a rule follower — an embodiment of her now-famous idea of "the banality of evil."

Alas, Arendt's stance proved that hate mail and knee-jerk reactions existed long before Twitter. Absurdly, because she refused to view Eichmann as some sort of fire-breathing devil, Arendt was attacked as a "self-hating Jew" and a "Nazi defender." She would not be cowed, though, and von Trotta's film, which features a commanding lead performance by Barbara Sukowa, shows the value of individual, contrarian voices.

Hitchcock

"Hitchcock" currently has a Rotten Tomatoes score of 60 percent, which means it is hanging on to its "fresh" status for dear life. If it drops by just 1 percent, that ripe tomato will turn into a green, ignominious splat. Of course, the "Tomatometer" is not the be-all and end-all, but a rotten fruit would still be a slight against this highly entertaining biopic.

The film recounts the making of "Psycho," Alfred Hitchcock's infamous mid-career classic. We see the production's controversies and the risks Hitchcock took in committing to it, namely an eye-watering financial investment. We also see moments on set, with Scarlett Johanson and James D'Arcy appearing as Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins. The force of the film, though, is the relationship between Hitchcock (Anthony Hopkins) and his wife, Alma Reville (Helen Mirren). Reville was not just Alfred Hitchcock's wife. She was his advisor, editor, and collaborator. She also carried Hitchcock through domestic life, especially finances, which he handled terribly. Hopkins and Mirren share an enjoyable chemistry, depicting an often one-sided marriage with a lack of intimacy that belies a deep, meaningful bond.

Despite Mirren's performance, Sacha Gervasi's film is all about Hopkins, who plays the Hitchcock of "Alfred Hitchcock Presents," a wry, charismatic Englishman with a mischievous, knowing twinkle in his eye. It may not be the Hithcock that Tippi Hedren knew, but it's not a performance without anguish, either. It may be a bit light and frothy, but "Hitchcock" is still a bit of fun.

Tucker: The Man and his Dream

After "Apocalypse Now" in 1979, Francis Ford Coppola's career fell along with New Hollywood. Indeed, his 1982 film "One From the Heart" is sometimes named alongside "Heaven's Gate" as one of the death knells of the period, owing to the musical's disastrous box office performance.

Coppola followed that misfire with a series of further bombs such as "Rumble Fish," "The Cotton Club," and "Gardens of Stone." Before the director returned to his roots with "The Godfather: Part III," Coppola released "Tucker: The Man and his Dream," which was yet another financial dud.

This is a pity because "Tucker" is a biopic brimming with charm and energy. It tells the story of Preston Tucker, a Michigan entrepreneur known for the Tucker 48, a chromed, glossy sedan that was a small marvel of automotive engineering. Indeed, marvelous enough to threaten Michigan's industrial establishment, which set its sights on the plucky entrepreneur.

In the role of Tucker is Jeff Bridges, who strides across the screen with all-American charm. Decent, confident, and individualistic, Tucker is the personification of the American dream, and his force of character is complemented by warm lighting, swinging music, sharp tailoring, and nostalgic locales. Coppola's film is essentially a Norman Rockwell painting at 24 frames per second — and that's a good thing.

Chopper

Society has long made celebrities of criminals. America had Al Capone, Britain had the Kray Twins, and Australia had Mark "Chopper" Read, the notorious jailbird and self-described "garbage disposal" expert. By garbage, Chopper was referring not to household waste but to the thugs and drug dealers of Melbourne, Victoria. Chopper claimed to have killed 19 such people in elaborately cruel ways (knives, guns, bolt cutters, cement mixers). Despite his capacity for violence, Chopper was not to be taken too seriously. The man was a showman and a liar whose favorite idiom, "Never let the truth get in the way of a good yarn," served as a winking caveat to every grisly detail.

After a string of memoirs and books in the 1990s, Read's story became the subject of "Chopper" in 2000. It was Andrew Dominik's debut feature and it demonstrated the harsh realism of the filmmaker's aesthetic and innovative use of sound and image to heighten ambiance, often to macabre, unnerving effect.

However, "Chopper" belongs to Eric Bana. Sometimes, an actor who aligns with a biographical role so well that it is as if they were "born to play it." Bana's brilliant turn as Chopper is an example of this cliche. His likeness is nearly perfect and so are his mannerisms, namely the crude loquaciousness and the haywire violence that swells beneath his disarming and rather comical politeness.

Bernie

Director Richard Linklater is best known for "Dazed and Confused" and "Boyhood." Both are worthy of their reputations, but what about "Bernie," the quirky true crime biopic with Jack Black and Shirley MacLaine? The film concerns the relationship between Bernie Tiede (Black), an affable mortician, and Margie Nugent (MacLaine), a wealthy, cantankerous widow. They had very different standings in the small town of Carthage, Texas. Tiede was beloved by all who knew him, while Nugent isolated herself in a cold, rude manner.

Despite this, the pair was inseparable. They lunched together and traveled the world, spending many thousands of Nugent's dollars. This came at a price for Tiede, though. He was effectively her bellboy, running countless errands and enduring her obnoxious moods. Eventually, after some time of perceived imprisonment and abuse, Tiede shot Nugent dead.

In telling this story, Linklater invited Carthage locals to appear on camera and even act. The result is a novel docudrama of uncommon heart and charm. Yes, it's a film about the murder of an 81-year-old woman, but the complexities of personality, bias, and justice skew your moral compass. He should never have picked up that .22 rifle, but does that negate Tiede's winsome nature? Jack Black is the lynchpin in all of this. Dorky, portly, and mustachioed, his performance is a career-best. There's so much fun, sass, and infectious energy in him. The character allows Black to play to his mischievous, theatrical flair while flexing his dramatic chops but never in a showy, self-indulgent manner.

Kinsey

Liam Neeson has been taking out the trash for years now, killing countless terrorists, kidnappers, and wolves. Yet, there was a time when Neeson appeared in sensitive biographical dramas like "Schindler's List," "Michael Collins," and "Kinsey," the Bill Condon-helmed biopic from 2004. Neeson assumes the role of Dr. Alfred Kinsey, the sexologist famed for his sweeping studies of human sexuality in the 1940s and 1950s. Kinsey's two leading works, "Sexual Behavior in the Human Male" and "Sexual Behavior in the Human Female," are based on interviews with thousands of subjects whom we see in numerous montages.

These people include naive newlyweds, chaste middle-aged men, and an older lady who, when asked about masturbation, claims, "I invented it, son." There are many moments like this that treat sex with openness while recognizing that it can be, well, quite funny. It's not all red cheeks and double entendres, though. Dr. Kinsey and his team meet deviants who challenge the limits of their work and methods. The doctor has tyrannical moments, too, namely an argument at the dinner table in which he resembles his abusive father, whom the young Kinsey had once dubbed "a prig, a skinflint, a petty tyrant, and a hypocrite to boot."

Condon's take on Kinsey may skew positive, but his film is not a hagiography. We see the biologist's obsessiveness and questions are raised about his methods, albeit fleetingly. Ultimately, "Kinsey" credits the man for his help in shifting conversations about sex away from fear and into a place that was altogether more open and understanding.

Pasolini

"Pasolini" is Abel Ferrara's love letter to Pier Paolo Pasolini, the controversial Italian director best known for "Salo," which took the Marquis de Sade's "120 Days of Sodom" and repurposed it for Fascist Italy.

Now, anyone who wants to see Ferrara's film is likely aware of "Salo" and Pasolini's other works. Yet, this biopic is a niche experience even for those with a passing knowledge of the late Italian filmmaker. It does not follow the beats of a conventional biopic. It is instead a meditative vision that is more interested in the filmmaker's ideas than the narrative threads of his life. In short, it is an art film about a maker of art films.

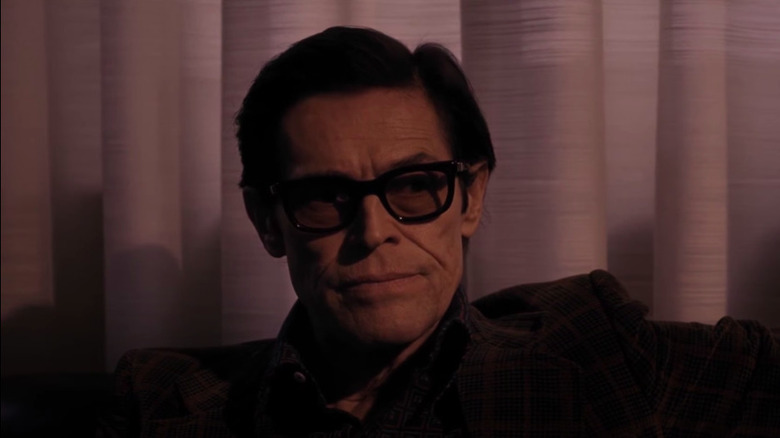

With his lean frame and high cheekbones, Willem Dafoe has the right physicality for the role. He has the range and curiosity, too. Is there anything Dafoe doesn't have as an actor? Yes, actually, and that is the ability to speak Italian or affect an Italian accent, which can be a distraction in a film about an Italian cultural figure.

First Man

"First Man" should have been huge. It should have grossed hundreds of millions of dollars and joined the ranks of "Apollo 13," "Gravity," and "Interstellar." However, during its run in the fall of 2018, Damien Chazelle's film earned just $105 million on a $59 million budget. Perhaps that has something to do with Neil Armstrong. Ryan Gosling is distant and unflappable as the first man on the moon, interpreting his private nature in a performance that official Armstrong biographer James Hansen called a "great job." It may make for better history, but Armstrong's severity could be a surprise — and a downer.

There is a procedural manner to Chazelle's film, too. We feel the danger and sacrifice of the mission but not necessarily the excitement. Instead of a technicolor adventure à la David Lean, "First Man" is a film of mourning, preparation, and stern conversations. Then, there are the bone-rattling flight sequences, which are chaotic masses of warping metal, sparking cables, and head-crushing physics.

Don't take any of this as criticism. Chazelle's vision may be less fun than whatever Steven Spielberg could have come up with, but it is no less worthy of your attention. Even if you consider "First Man" to be hard work, your investment will be rewarded by the landing sequence. It is matter-of-fact like the rest of the film, but there is real cinematic awe to it.

Nixon

How did one of Oliver Stone's best films become such a footnote in his career? The director may be famously on the left of the political aisle, but he recognized the complex humanity in Richard Nixon's character. Fortunately, so did Anthony Hopkins, whom Stone approached for the role. Together, they created one of the finest biographical character studies of the last 30 years. Hopkins negates his lack of physical likeness to the disgraced president by focusing on Nixon's mannerisms and complexes, which were shaped by his poor upbringing in rural California.

Nixon was an intelligent and motivated student but, by many accounts, an awkward, introverted presence who harbored much resentment toward establishment circles, which he saw as charmed, arrogant, and overrated. He took this angst and alienation into the White House, where it manifested in anger and paranoia that led inexorably to the Watergate scandal.

Hopkins embodies this character arc, and it is simply fascinating to watch. Sometimes, there is no greater cinematic pleasure than watching a great actor in a great role.

Capone

Part of Tom Hardy's appeal as an actor is his sketchy, off-beat energy. That sounds like an insult, but it isn't. It was this energy that made "Venom" enjoyable for me, and I pretty much hate the MCU. However, Eddie Brock's sweaty unkemptness is positively hygienic compared to the bodily morass we find in "Capone," the maligned gangster biopic.

The film is set during the twilight of Al Capone's life in Florida, a period in which his mind and body were destroyed by advanced syphilis. Hardy interprets this in the most corporeal way imaginable, reducing Capone to a growling husk of a man who can barely stay lucid and repeatedly soils himself. I'm not sure whether this is Hardy being faithful to history or just indulging his flair for going goblin mode. Either way, it makes for an interesting performance and an off-beat, alternative entry in the Al Capone canon.