The 15 Greatest Clint Eastwood Movie Moments

Clint Eastwood's work has spanned the sports, music, drama, and romance genres, but he's best known as the antihero who takes out the trash with fists, bullets, and a few quips to boot. Eastwood took the baton from John Wayne, his spiritual predecessor, and revitalized the western with laconic bravado. Then, with "Dirty Harry," the actor kicked off the loose-cannon cop trope, spawning countless imitators.

However, some critics were less than impressed, especially early on. Pauline Kael wrote, "[He] isn't an actor, so one could hardly call him a bad actor. He'd have to do something before we could consider him bad at it." According to the late Sonda Locke, Eastwood's former lover, the actor dismissed Kael's barbs as psycho-sexual vengeance.

Eastwood may not be one of the great actors, but he is one of our great stars, and there are many "great" moments to draw on, accordingly. So, from "A Fistful of Dollars" and "High Plains Drifter" to "Unforgiven," "Gran Torino," and "The Bridges of Madison County," etc., here are the greatest Clint Eastwood movie moments as an actor — which include moments from movies he directed and more than one moment from a few of the same films.

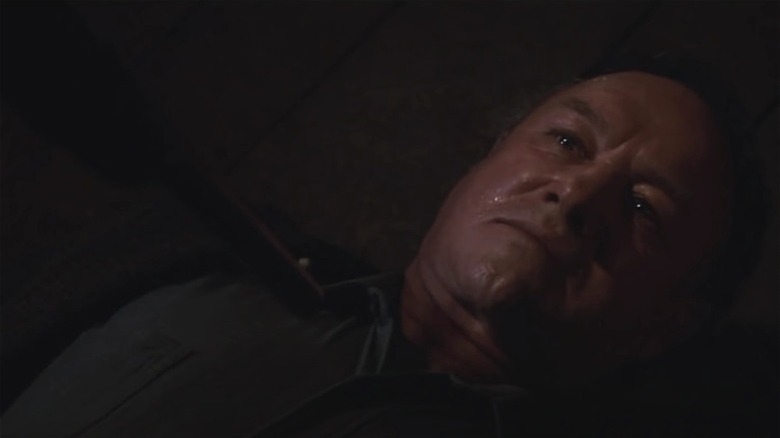

Standing in the rain - The Bridges of Madison County

"The Bridges of Madison County" is all the weepy proof you need that Clint Eastwood does in fact have feelings, and the zenith of this weepiness occurs in the film's closing moments. But first, some context.

Robert Kincaid (Eastwood) is a photojournalist visiting the historic covered bridges of Madison County, Iowa. He has a truck and a camera but little sense of direction, so he asks at the farm of Francesca Johnson (Meryl Streep), a housewife whose husband and children are away at the state fair.

The attraction is immediate, perhaps even "love at first sight." Francesca rides with Robert to Roseman Covered Bridge, where she shows him around and even poses for the camera. Any pretense of friendship quickly becomes untenable and the pair embark on an intense four-day affair, but it is not to be. Francesca is unwilling to desert her family and her mind questions what may be her heart's excesses.

They last meet eyes at an intersection in town with the heavens open for full dramatic effect. Such a moment would be gooey treacle in other circumstances, but Eastwood dilutes the melodrama with a wistful, elegiac tone.

Confronting Little Bill - Unforgiven

There's a lot of violence in "Unforgiven," but most of it is heard, not seen. We're told that William Munny (Eastwood, a best actor Oscar nominee) was about as violent as a man could be before he retired to his Kansas farm. We're told that he was a drunk, a scoundrel, and a murderer of women and children. Some of it is hearsay, but most of it isn't; Munny recalls the people he maimed and killed without filter. He's not a boastful man but not a repentant one, either. Instead, he is an amoral nihilist who grinds through life with little thought paid to purpose or meaning.

Munny is washed up at the start of "Unforgiven"; he can't shoot straight or even mount a horse with any dignity. But by the film's end, after a bounty has sharpened his aim and his nerve, Munny returns to his lethal default, and there are few better targets it could find than "Little Bill" Daggett (Gene Hackman), a bellicose small-town sheriff.

The confrontation between Bill and Munny is the final deconstruction of this revisionist western. Munny is not an honorable figure of American folklore. We see him kill men regardless of whether they're armed or even facing him. His violence is steered not by honor but by vengeance, spite, or nothing at all. There are no good guys or bad guys here, just shades of immorality. It's a compelling send-off to an icon of the western genre.

Get three coffins ready - A Fistful of Dollars

If Eastwood is known for anything, it is the vengeance fantasy sequence. These moments are found throughout Eastwood's career and they invariably concern one of Eastwood's antihero characters and a group of men looking to cross him. Naturally, such men never fare well and Eastwood barely breaks a sweat. All of these moments, from "Dirty Harry" to "Gran Torino," have their roots in "A Fistful of Dollars," the film that introduced Eastwood to the world.

The first of the "Man With No Name" trilogy casts Eastwood as an enigmatic drifter who arrives in San Miguel, a small border town split between two warring families. The stranger's presence turns heads and attracts the attention of three rogues who fire shots at his mule, scaring it off.

Most men would lay low or skip town, but the stranger is not most men. He collects himself, asks around, and approaches the men when the time is right. "Get three coffins ready," the stranger says, addressing a wizened old coffin maker. Moments later, the stranger begins his confrontation with the three men — and a fourth one to boot. All the spaghetti western tropes are there: spitting, staring, and cackling laughter that gives way to an intense, hand-hovering staredown before the inevitable staccato of gunfire.

Right turn, Clyde - Every Which Way but Loose

Critics were never kind to "Every Which Way But Loose," the curiously titled orangutan comedy from 1978. Janet Maslin dismissed it as, "the slackest and most harebrained of Mr. Eastwood's recent movies." I don't think I'd be that rude, but she does have a point: it's not great. Audiences didn't care, though. Eastwood's offbeat gamble became one of the most successful films of his career, earning $104.3 million.

The 114-minute running time of "Loose" may be too long and baggy, but this article considers only "moments" of Eastwood's career, and with Clyde the orangutan being such a charismatic performer, there are several to choose from.

The only plot detail you need to know here is that Philo Beddoe (Eastwood) is a trucker, a bare-knuckle fighter, and the owner of an orangutan called Clyde. Beddoe is capable of handling himself, but Clyde has the stronger right hand and he will use it at the command of, "Right turn, Clyde." The best example is the first one. A biker gang rides alongside Beddoe's truck and taunts him with inane jibes. Ignoring them, Beddoe gives the cue and Clyde throws his hairy orange fist into the lead biker's face, sending him and his crew sideways like a set of dominoes. World-class cinema? No. Funny? Yes.

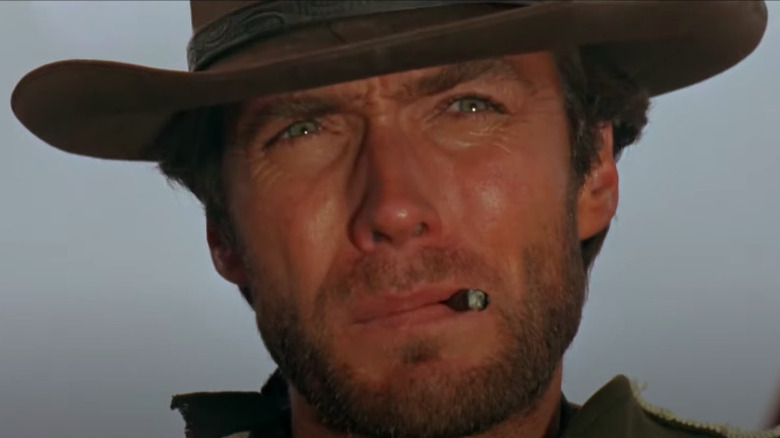

Mexican stand-off - The Good, The Bad and the Ugly

Here is a defining moment of Eastwood's career, the western genre, and movie history. Blondie (Eastwood), Angel Eyes (Lee Van Cleef), and Tuco (Eli Wallach) have crossed the American Southwest in search of Confederate gold and the end is finally in sight. Each man possesses a thread of information about the treasure's whereabouts and they are led, inexorably, to a desert valley cemetery shouldered by mountains. Blondie has Tuco under control; the "Good" shoots, the "Ugly" digs. But when Angel Eyes appears moments later, the solution can no longer be peaceful.

What follows is a Mexican standoff and about five minutes of cinematic majesty — a sun-beaten amalgam of sweeping vistas, anxious close-ups, and one of the finest scores in all of cinema.

You may think that the cemetery is in a remote corner of Mexico, but it can actually be found in Burgos, a northern province of Spain. Built for the film by Spanish soldiers, the cemetery fell into disrepair until the mid-2010s, when a team of volunteers restored it in anticipation of the film's 50th anniversary.

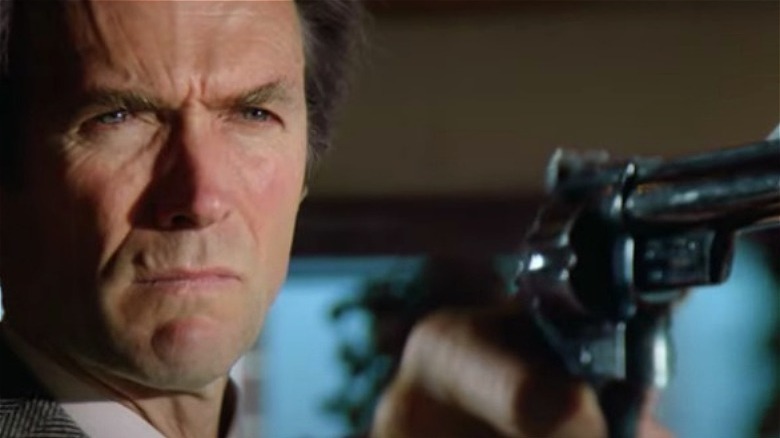

Do you feel lucky, punk? - Dirty Harry

The first utterance of "Do you feel lucky, punk?" occurs early in "Dirty Harry." Inspector Harry Callahan (Eastwood) is enjoying a hotdog when robbers shoot their way out of a bank across the street, forcing Harry to end his lunch break and confront them with his .44 Magnum revolver.

After a brief shootout, Harry takes a moment to swallow his hotdog and approaches one of the injured hoodlums. "Uh-uh," Harry says, as the criminal reaches for his shotgun, "I know what you're thinking. 'Did he fire six shots or only five?' Well to tell you the truth in all this excitement I kinda lost track myself. But being this is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world and would blow your head clean off, you've gotta ask yourself one question: 'Do I feel lucky?' Well, do ya, punk?"

Harry delivers this not with anger but with levity. He may be "dirty," but Harry wouldn't endanger an unarmed, garden variety thief (and he's too good a marksman to forget how many shots he fired).

However, there is no such levity during the second utterance of this line, when Scorpio (Andrew Robinson), a deranged serial killer, looks down the barrel of Harry's gun. By this point, Callahan has lost all faith in the SFPD's ability to stop this man. So, after narrowly saving the life of Scorpio's latest victim, Harry addresses him in a distinctly bitter tone, goading the killer to pick up his gun so that he can end him. It's all part of the film's troubling, noirish morality.

Get in the truck - Gran Torino

Eastwood was nudging toward 80 when "Gran Torino" began shooting in the summer of 2008; he knew he could still kick ass, he just had to do it the right way. As Walt Kowalski, a jaded widower and Korean War veteran, Eastwood could have locked, loaded, and blasted his way through Detroit's Highland Park neighborhood, a place blighted by decay and gangs. However, such a gung-ho tact would've been predictable. Instead, Eastwood played with the threat of his violent on-screen reputation without going full-blown "Death Wish," making "Gran Torino" a suspenseful exercise in vigilante brinkmanship.

The film is typified by a clash between Kowalski and some street-corner thugs who taunt Sue (Ahney Her), Kowalski's neighbor, and Trey (Scott Eastwood), Sue's date. Kowalski pulls up in his truck and announces himself, "Ever notice how you come across somebody once in a while that you shouldn't have f***ed with? That's me."

Hearing this from a gnarled, 78-year-old misanthrope is pretty funny and Eastwood is fully aware of it. "Gran Torino" is no vanity piece. He presents Kowalski as a curmudgeon who doesn't care what people think of him. In fact, Kowalski plays up to notions of senility by shaping his hand like a gun and pointing at the hoods as if they're playing a child's game. He's not, of course, and Kowalski makes himself clear with his military-issued Colt 1911. With millions of views on YouTube, it is perhaps the last great Eastwood "badass" moment.

Frank consults his priest - Million Dollar Baby

Eastwood may personify the "strong silent type," but tenderness, though rare, does not elude him as an actor. In "Million Dollar Baby," Eastwood stars as Frankie Dunn, a tough and taciturn boxing trainer who's a comfortable fit for the actor's range. However, what begins as an underdog boxing story ends as a harrowing issue drama about euthanasia, and Eastwood rises to the dramatic challenge.

Frankie rejects Maggie (Hilary Swank) when he sees her flailing against a heavy bag in his Los Angeles gym. She's too small, too old, and a woman. But Maggie's eagerness forces his hand and, very quickly, she becomes a formidable fighting force. All of that is history when Frank consults his priest, though. Maggie can no longer fight. She can't even lift a finger. The basics of life are now beyond her control, and Frankie is the only person she trusts to do what she feels is right for her.

Father Hovark (Brían F. O'Byrne) listens quietly as Frankie explains his anguished dilemma. Eastwood displays a range that some wouldn't have thought possible. His voice breaks, his lips tremble, his nose runs and so do his eyes. Such details wouldn't be a big deal for most actors, but seeing them in Eastwood is a novel — and powerful — experience, and he earned the second of his two best actor Academy Award nominations for his performance.

Go ahead, make my day - Sudden Impact

After "The Enforcer," the last Dirty Harry film of the 1970s, Eastwood took the directorial reins of "Sudden Impact" and smashed into the 1980s with an outrageous slap bass score by Lalo Schifrin and a brand-new catchphrase: "Go ahead, make my day."

Inspector Harry Callahan's day begins like any other. He drops by his local diner for a large black coffee poured by Loretta, his dutiful server of some 10 years. However, as he walks back to his car, Harry finds that his coffee is sitting on about a pound of sugar. Alarmed, he returns to find a group of armed punks casing the joint for wallets, watches, and anything of value.

Clearly, Harry will handle these guys, no problem. There's no doubt (or tension) about that. But the pleasure here is in the dialogue, penned by Joseph Stinson and script doctor firebrand John Milius. My favorite line arrives just before the famous one. "Who's we, Sucka?" asks a robber when Harry suggests he is not alone. "Smith & Wesson and me" is the ridiculous answer.

"Go ahead, make my day," comes a short while later after he's cleared the diner of all but one of the criminals, who has backed himself into a corner with a gun and a hostage. Milius must have sipped a beer after he came up with that one. The pithy riposte is so versatile that even President Reagan used it at the 1985 American Business Conference.

Bus destruction - The Gauntlet

"The Gauntlet" is a big '70s action road movie that sacrifices plot for car chases, gunfights, and fiery spectacle. It also features Eastwood playing against type as Ben Shockley, a bumbling detective prone to drowning his sorrows.

Shockley is tasked with transporting Augustina Mally (Sondra Locke), a so-called "nothing witness," from Las Vegas to Phoenix. However, it transpires that she's not a "nothing witness" at all but a mobbed-up sex worker with kompromat on Commissioner Blakelock (William Prince), Shockley's corrupt boss.

A cat-and-mouse plot ensues involving cops and criminals armed with all sorts of weaponry and equipment. Again, it's light on sense and plausibility but it is an expensive showcase of practical effects that are few and far between in our age of computer-generated imagery. When things went boom, they really went boom. The most indulgent of these occurs in the final scene when an armor-plated bus driven by Eastwood must endure a gauntlet of the state's best marksman, who rain a seemingly never-ending hailstorm of lead into it.

Hell of a thing, killing a man - Unforgiven

"Unforgiven" is a western rich in revisionist themes; its characters, dialogue, and imagery conspire to deconstruct the genre and the myths of the American West. Perhaps the most enduring moment is an aphorism delivered by William Munny (Eastwood) on a windy, Wyoming landscape: "It's a hell of a thing, killing a man. You take away all he's got and all he's ever gonna have."

It is a simple yet poignant line. It humanizes an act –- murder –- that can be so thoughtless and so terribly easy. Killing a person often requires little more than the movement of one's index finger. In an instant, decades of character and experience are reduced to a memory that will fade and then likely die with those who knew them.

It is curious that William Munny, a self-confessed murderer, would say such a thing. There may be contrition somewhere in Munny's psyche, but his dominant perspective is one of cold, hard amorality.

Barber shootout - High Plains Drifter

"High Plains Drifter" is one of Eastwood's best westerns and a particular scene helps explain why. The barbershop is a common fixture of the western genre, and it's usually a sanctuary, but nothing is quite right in the mining town of "High Plains Drifter," a film with a dark, supernatural quality.

Eastwood is the titular drifter and he rumbles into town looking for a shave. The local barber obliges, but three hired gunmen don't take kindly to his presence. It's familiar stuff, granted, but it's a case of execution over originality. Vital to this scene is William O'Connell as the barber. A longtime Eastwood collaborator, O'Connell gives a supporting turn that's much better than it "needed" to be. The scene lasts for all of three minutes, but the character actor loads his screen time with oddball anxiety and reactive detail. He is the connective tissue that ratchets up the tension between the drifter and his enemies, whom the drifter dispatches with typically high-impact flair.

Hangman scheme - The Good, The Bad and the Ugly

Here's another piece of classic Eastwood. Blondie (aka The Man with No Name) may be the "Good," but he's still pretty bad. Not to the extent of Angel Eyes (Lee Van Cleef), of course, but Blondie is every bit as crooked as Tuco (Eli Wallach), the titular "Ugly." He's in cahoots with the man, after all. Their scheme is for Blondie to present Tuco to a sheriff, collect the bounty, and then shoot the hangman's noose moments before execution and flee to safety. They will then share the loot before moving on to the next town.

We see this racket unfold with that brilliant spaghetti western magic: the music, the scenery, the sound effects, the slapstick gunplay. "The Good, The Bad and the Ugly" concludes a trilogy that begins well, gets better, and then stands over just about everything in the canon.

Waiting for Scorpio - Dirty Harry

This moment gives me chills. Scorpio (Andrew Robinson) is already a killer of men, women, and children, but he manages to up the ante by hijacking a school bus with about half a class of children on it. With the bus heading north into Marin County, Scorpio paces the aisle cajoling the kids with nursery rhymes and other weird, child-like gestures. When some children begin to question him, the killer breaks into a frenzy and even hits one child for his lack of enthusiasm. It's an intense scene that's not lost its disturbing, haywire energy. In fact, Robinson's performance was so convincing that it attracted death threats from those who struggle to separate fiction from reality.

Meanwhile, back at City Hall, the mayor speaks limply about appeasing Scorpio's demands. Inspector Callahan (Eastwood) always took a hard line on the killer, but now he's outright disgusted by what he's seeing. He refuses the mayor's request to deliver Scorpio's ransom and leaves the room without stating any intention.

Back on the bus, Scorpio continues to terrorize the children and the homely woman driving the bus, screaming obscenities and waving around a pistol. Lalo Schifrin's score builds, too, rising to a crescendo that breaks when Scorpio, dumbfounded, spots Callahan in the distance waiting for him on a railroad bridge. Finally, this dreadful, spiraling situation has its savior — and it's brilliant, fist-pumping cinema (metaphysically, of course, I don't get that carried away).

Harry jumps onto the bus - Dirty Harry

The iconic moments come scene by scene in "Dirty Harry." As Scorpio takes control of the bus and speeds under the bridge, Callahan positions himself and jumps onto the vehicle's roof, hanging on for dear life as Scorpio shoots at him from within. Such a maneuver would be an intermediate task for a stuntman, but there was no stand-in for 40-year-old Clint, as he did it himself. Misjudging the bus's speed would have seen limbs meet tarmac from a height of about 15 to 20 feet.

Eastwood tested his physicality throughout the 1970s. He dangled from the hood of a car in "Magnum Force," scaled treacherous rock faces in "The Eiger Sanction," and raced a motorbike for the chase sequences in "The Gauntlet." If there was one man who could dissuade Clint from a stunt, it was his long-time double, Buddy Van Horn. "There's been a couple of times that he's wanted to do something and I talked him out of it," Van Horn told the Independent. "He's a pretty physical guy and likes to do his own stunts ... He's been banged up a few times."