15 Best Films Of The 1930s

Just a few short years after the introduction of sound, 1930s cinema would explode with possibilities. Filmmakers creatively experimented with not just musicals, introducing song and dance to the big screen, but screwball comedies, which featured fast-paced, witty dialogue that title cards in silent film never would have been able to keep up with. As Hollywood experienced an early golden age, the world was plunged into an economic depression, which the movies would respond to with both social issue films as well as glittery escapism. Indeed, the films of this decade seem to fall largely into those categories: Movies that were made to shine a light on the problems that their audiences faced and those made to distract them.

From horror to comedy, romance to war, the 1930s saw Hollywood diversifying and churning out films that catered to fans of different genres. With the studios operating like well-oiled machines (often at the cost of their stars' happiness and well-being), their biggest obstacle was making sure nothing they made would run afoul of the newly implemented Hays Production Code, which dictated what films could and could not show. A decade of contrasts, the turbulent 1930s produced some of the most interesting and creative films of the 20th century.

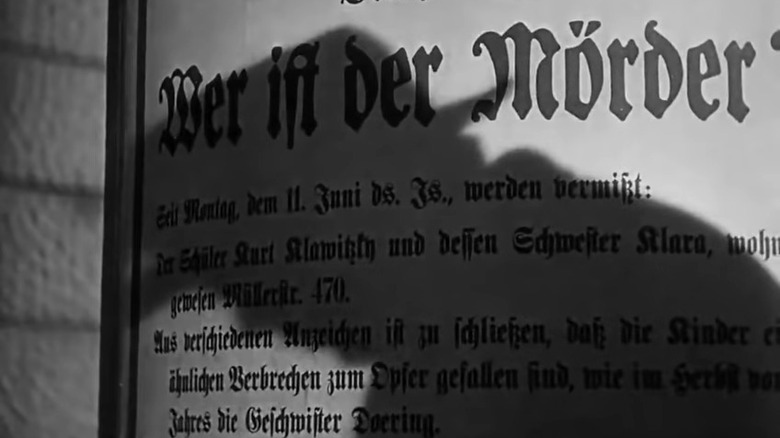

M

Fritz Lang's "M" remains one of the darkest cinematic entries of the 1930s, with Peter Lorre playing a child murderer who spends the entire film attempting to evade justice for his crimes. "M" creeps along the seedy underbelly of Berlin (both Lang and Lorre would eventually go on to have successful careers in Hollywood, but in 1931 were still working within Germany), so deeply disturbing that it almost feels like a precursor to the criminal antics of film noir a decade or so later.

Lang cultivates an atmosphere that is foreboding and distasteful, and it's shocking to realize that he doesn't include violent content at all, relying on the gruesome imaginations of audiences to fill in the blanks. Graham Greene described Peter Lorre's expressive face in the film, saying that his "marbly pupils in the pasty spherical face are like eye-pieces of a microscope through which you can see laid flat on the slide the entangled mind of a man: love and lust, nobility and perversity, hatred of itself and despair jumping out at you from the jelly."

Death Takes a Holiday

Do you remember the Brad Pitt movie "Meet Joe Black," in which he stars as Death himself, who decides to explore the world for a little while in a human body? It's actually a remake of "Death Takes a Holiday," a 1934 film starring Fredric March, who takes a break from escorting souls to their eternal rest to learn a bit about this whole humanity business. He poses as a foreign prince and, having been human for all of five minutes, he promptly falls in love with a beautiful young woman.

Now that he has someone he cares about and by extension, something to lose, he understands a bit more why he and his veil of death are so feared. "Death Takes a Holiday" was a financial success for Paramount, and its philosophical musings seemed to have struck a chord with audiences — the studio reportedly received thousands of letters from fans who claimed that the film's depiction of death helped them come to terms with their own mortality.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

Animation existed well before Walt Disney started putting together storyboards with adorable, cheery animals, but "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" would prove that animated films could serve as more than just brief entertainment to be doled out before the main feature. In the right hands, these movies could be as artistically inspired and (perhaps more importantly, to studios) financially viable as their live-action counterparts. "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" is a classic fairy tale about a beautiful princess who is cast out by her jealous stepmother and finds a home in the woods with a troupe of eccentric miners.

The animation is delicate and incredibly detailed, giving the film an old-world atmosphere, and each of the dwarfs has such a distinct personality and unique relationship with Snow White that nearly 100 years later, we still know each of their names. "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" was the first feature-length success for Walt Disney. It earned him an honorary Academy Award (which, charmingly, featured one full-sized Oscar and seven miniatures) and to this day, it holds the record for the highest-grossing animated film (adjusted for inflation and accounting for several re-releases, that is).

City Lights

By the time "City Lights" came out in 1931, Charlie Chaplin had been one of the biggest stars in Hollywood for over a decade, having transitioned from comedy shorts into feature-length films that he directed. "City Lights" is one of his better films and undeniably his most romantic. He takes the character of the Tramp and casts him as an unlikely romantic lead, falling in love with a blind flower girl (Virginia Cherrill) who mistakes him for a millionaire.

Their relationship is allowed to blossom unhindered until she is given the chance to have an operation that will restore her sight and reveal his deception once and for all. Despite the raggedy outfit and ill-fitting shoes, Chaplin's Tramp usually seems comfortable in his skin, but in "City Lights," he is shaken by the knowledge that he isn't good enough for the woman he loves. It's this emotional note that makes the performance so emotionally affecting.

Scarface

"Scarface: The Shame of a Nation" stands at a crossroads in film history. It marks the transition between the pre-Code era and the censorship of the Hays Production Code better than any other movie. It stars Paul Muni as a Chicago gangster (loosely based on Al Capone) who climbs the ladder of a criminal bootlegging syndicate until he essentially runs the South Side. But he's ambitious, perhaps too much so, because the temptation to pick a fight with the North Side gangs is too powerful to resist.

His crimes catch up with him (as they must do, according to the Hays Code), leading to a standoff with the police that will inevitably end badly for him. Muni's performance as Tony would define the gangster genre, creating an almost animalistic figure whose presence is equal parts magnetic and ominous. The cynical depiction of the American Dream (the film ends on a twinkling billboard proclaiming that "The World Is Yours") in "Scarface" is a reflection of a 1930s cultural landscape that had lost its sense of optimism.

Ninotchka

A film that feels somehow incredibly ahead of its time, "Ninotchka" is a clash of juxtapositions — capitalism and communism, utilitarianism and decadence, femininity and masculinity — cheekily bound together in a way that only director Ernst Lubitsch could pull off. Greta Garbo stars as Ninotchka, a stern-faced Soviet who travels to Paris to conduct a study on Western engineering. However, it isn't long before her strong communist ideals are shaken by both the relentless temptations of capitalist opulence and the appeal of a certain charming French count (Melvyn Douglas).

The film portrays a gently satirical interpretation of Soviet Russia that still manages to capture an atmosphere of paranoia and intrigue in which neighbors turn in neighbors to the secret police. Garbo is at her best here, bringing humor and poignancy to Ninotchka's internal struggle with two incredibly distinct cultures. Despite any offense it may have caused Stalin and his cronies (it was, unsurprisingly, immediately banned in the U.S.S.R. and its satellites), it was a tremendous critical success and was nominated for four Academy Awards in 1940.

The Wizard of Oz

It would simply be impossible not to include "The Wizard of Oz." It's not just one of the most important films of the 1930s. It's one of the most important films of all time. With so many iconic moments — the dramatic transition from dull sepia to full Technicolor, Judy Garland's melancholy rendition of "Somewhere Over the Rainbow," the harrowing flight of the Wicked Witch of the West's troupe of monkeys — "The Wizard of Oz" has embedded itself into the cultural landscape in a way that few movies have.

Garland plays Dorothy, a young girl from Kansas who is swept away to the land of Oz in a tornado and must confront the Wicked Witch of the West to find her way back home. The charm of Garland's performance made her a Hollywood star, and she grounds the film in a plaintive, earnest reality whenever it starts to feel overwhelmed by its more fantastical elements. Visually imaginative and brimming with vivid color, "The Wizard of Oz" evokes a sense of magic in its world of make-believe.

Holiday

In 1938, Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant teamed up on two screwball comedies that went on to define the genre. The first was "Bringing Up Baby," which is arguably the more famous of the two, and the second is "Holiday," which is underrated but delightful in its own way. Grant stars as a self-made man who has worked his entire life and is determined to retire while he's still young and can enjoy himself.

So what's the problem? His fiancee, Julia, to whom he has rather impulsively proposed after meeting her on vacation, expects him to take on a respectable position at her wealthy father's company. After meeting her family, it becomes clear that the woman with whom he has the most chemistry is not Julia but her sister Linda (Hepburn), the black sheep. They are a delight together and have such a joyful camaraderie on screen that it's easy to see why they would become one of the most memorable pairings of the 1930s.

It Happened One Night

"It Happened One Night" is remembered most distinctly for two things, both of which highlight the tightrope of sexuality that films from this period were forced to walk. The first is Claudette Colbert, as Ellie, famously lifting up her skirt to expose her leg in an effort to attract a ride as she and Peter (Clark Gable) hitchhike — a move that was so scandalous that Colbert used a stunt double (until she realized that her legs were sexier than the double's, and she agreed to do the scene).

The second is the iconic "Wall of Jericho," a sheet hung between Ellie and Peter to divide the room that they share, preserving some modicum of respectability and making it clear to audiences that there was no funny business going on between the characters. This veneer of propriety made their chemistry all the more electric, and Gable's shirtless scenes had such an impact on viewers that it was believed that he tanked the undershirt industry overnight. "It Happened One Night" was also a massive critical success, winning the big five Academy Awards: best picture, best actor, best actress, best director, and best writing.

Freaks

When Tod Browning turned in his cut of "Freaks," a disturbing morality tale set against a backdrop of a carnival freak show, MGM didn't know what to make of it. The film stars a cast of real-life carnival show workers and tells the story of a trapeze artist who schemes to marry Hans (Harry Earles), a wealthy little person in the show, but when the community of "freaks" learn of her plans to steal from and humiliate him, they take their revenge on her — with grotesque consequences.

When the film was released, it horrified audiences, even after Browning allegedly cut an alternate editing that was even more gruesome than what eventually made it into the final version. Art director Merrill Pye said of a test screening, "Halfway through the preview, a lot of people got up and ran out. They didn't walk out. They ran out." Despite this, "Freaks" has since gone on to develop a reputation as one of the most interesting films of the 1930s thanks to a surprisingly empathetic portrayal of its "freak" characters that showcases their strong sense of loyalty to their community and their ability to adapt to their disabilities and lead largely independent lives.

The Adventures of Robin Hood

With the advent of sound and more sophisticated film techniques, 1930s Hollywood was suddenly awash with huge, splashy adventure films. And each of these needed a handsome, outrageously charismatic leading man, preferably one who knew his way around a sword. Enter Errol Flynn, one of the most iconic swashbucklers of the 1930s. Here, he plays the legendary Robin Hood, freshly returned from the Crusades and eager to right the wrongs of the evil Guy of Gisbourne (Basil Rathbone — who else?) and King John, who have launched a campaign of heavy taxation.

With exciting, imaginative fight sequences and a tremendous amount of chemistry between Flynn and his co-star Olivia de Havilland as Maid Marion, this is perhaps the definitive version of the Robin Hood story. It was a significant success upon release, winning three Academy Awards for best art direction, best film editing, and best original score.

The 39 Steps

You've probably had a few bad days in your time, but we're willing to bet that you've never accidentally found yourself embroiled in an espionage plot, forced to flee London to evade both the police and foreign spies who want to kill you for the information you now have. Alas, that's the fate of Richard (Robert Donat) in "The 39 Steps." When a female spy is killed in his apartment, he is tasked with finishing her mission — all while being implicated in her murder.

Not only is "The 39 Steps" one of Alfred Hitchcock's most effective thrillers (and that's saying something), but it also has a special place in the history of romantic cinema. To the best of our knowledge, it's one of the first on-screen examples of the trope in which an initially hostile couple is handcuffed to each other and forced to work together until they inevitably fall in love. Fast-paced, clever, and packed with twists and turns, "The 39 Steps" is a true gem of the era.

All Quiet on the Western Front

"War is hell," is a sentiment that we've all become acquainted with over the past century or so, but at the time of World War I when battles were supposed to be glorious, it was still something of a novel thing to say. "All Quiet on the Western Front" is based on a German anti-war novel by Erich Maria Remarque released in the 1920s. It follows the experiences of a group of German teenagers as they are sent to the front. Initially, they're full of patriotic zeal but quickly learn of the horrors of the trenches.

The scope of "All Quiet on the Western Front" is incredibly impressive. It is visually expansive while still managing to remain intimately focused on the lives of the young soldiers. Their growing disillusionment is heartbreaking to watch, especially when the characters return home on leave and have to witness the ignorant saber-rattling of the older generations. It would, perhaps inevitably, go on to be banned in Nazi Germany for its perceived anti-German message.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

Starring Fredric March and Miriam Hopkins, "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde" is one of the most interesting pre-Code horror films of the 1930s. March stars as the titular scientist, obsessed with the idea of splitting man into the two opposite sides of his nature: the good and the evil. One night, he drinks a potion that separates the two aspects of his personality. Dr. Jekyll remains the pure-of-heart, sexually repressed gentleman he's always been, and Mr. Hyde, a bestial, lascivious creature, roams the night in search of pleasures to soothe his id.

The film serves as a commentary on the duality of man and makes the argument that suppressing the darker impulses of his nature only serves to make them that much more powerful. However, the most impressive component of "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde" lies in its groundbreaking special effects. There's an incredible sequence in which Jekyll drinks the potion and, with the use of specific lighting and carefully applied makeup, his face morphs on-screen into that of Hyde. March would win an Academy Award for his performance in the film, making it the earliest horror movie to receive awards attention.

Design for Living

Polyamory seems like a thoroughly modern invention, a trend only possible in the socially liberated present when relationships outside the traditional heterosexual, monogamous marriage are embraced. At least, it would seem that way if you hadn't seen "Design for Living," a pre-Code gem that, in its depiction of a romantic threesome, feels very much ahead of its time. Gary Cooper and Fredric March star as George and Tom, a pair of American artists (one a painter, the other a playwright) living in Paris when they meet the beautiful Gilda (Miriam Hopkins) and quickly fall in love with her.

The only issue? She isn't interested in deciding which of them she likes best. Despite their best efforts to woo her, she seems to be most in love with whichever one happens to be around her at that given time. So rather than risk losing her or their friendship, they finally embrace the idea of one big, happy romance between the three of them. As radical as the film seems, it was toned down from the original play by Noel Coward, which more explicitly explored the romantic attraction between George and Tom.