Christopher Nolan On His Approach To Time In Oppenheimer And That Memento DVD Commentary [Exclusive Interview]

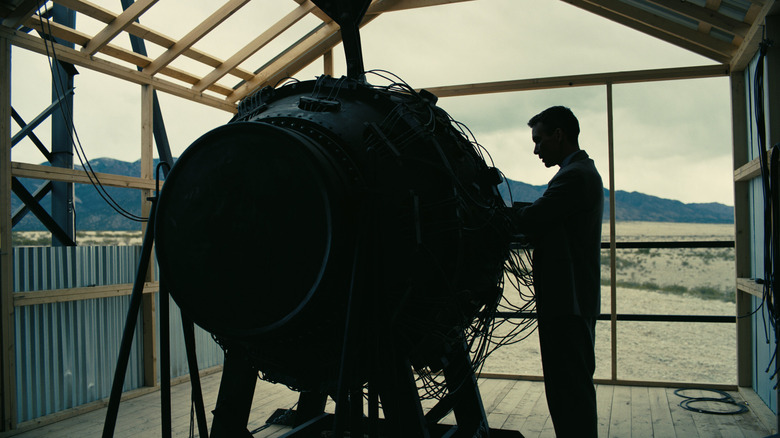

How do you make a movie like "Oppenheimer?" Given the film's massive box office success and cultural cache, it seems like a sure thing now. Yet, on paper, a three-hour biopic about the father of the atomic bomb who rushed headlong into creating our never-ending nuclear nightmare and then was pushed into ignominy by his own government, made primarily using practical special and visual effects, starring a huge ensemble of actors and shot on precarious (and prohibitively loud) IMAX cameras, sounds like anything but an easy bet.

But it's getting increasingly foolish to bet against filmmaker Christopher Nolan. With each successive film he makes, Nolan pushes the cinematic envelope stylistically and narratively without alienating general audiences, making him one of the relative few directors of his generation whose name has become synonymous with both artistic quality and financial success. While his more analog predilections may no longer be the norm in Hollywood, there's no denying he takes a great deal of care with his work, and that care extends to his films' home releases.

On the eve of the 4K UHD, Blu-Ray, and Digital release of "Oppenheimer," I had the pleasure of speaking with Nolan a bit about how he came to construct this massive film and how it functions as a culmination of his work thus far. I also got to pick his brain on the topic of cinema and its relationship to time itself, along with prodding to see if he'll ever record a commentary track for one of his films again, especially one like the innovative tracks he did for "Memento" and "Insomnia."

Note: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

'You don't want to feel stifled by a sense of responsibility'

There's a huge theme of accountability and responsibility in this movie. I know that tackling real life people and historical subjects artistically can be almost overwhelming if you let yourself get inundated with, "Oh, but what about my responsibility to the survivors?" or all of those other things. Did the book "American Prometheus" help you get over that hurdle?

Very much. Very much. No, you're quite right, and I don't know what your background is or what you're referring to in your own work, but it can be absolutely paralyzing. I first dealt with that on "Dunkirk," really. And my solution on that film was to invent the characters and say, "Okay, the bigger events I get from the research, but I'm just going to invent fictional characters to take you through the real events." This was kind of the opposite. It's like, "All right, we've got to get in the head of the man," if we have the information and research to do that, which "American Prometheus" provided. Martin Sherwin worked on that book for 25 years. Kai [Bird] worked with him for the last five years of it.

It's funny, I was having a conversation with Kai in New York recently. He asked me how long it had taken me to write the script. And when I really parsed out from when I actually started physically writing the actual screenplay, it was a matter of months. And he thought that was a very short period of time. And I said, "Yeah, I did 25 years of research before I started." [laughs] So that's the thing is they were ... my co-writers did 25 years' worth. So it frees you up emotionally as well.

It's also, weirdly, there's all kinds of feelings of responsibility. There's also legal concerns, copyright, those kind of things. Where, if you have a book that has everything you need, it's very freeing. It's a playground you play in. And you say, "Okay, I read that book and I trusted their interpretations of the fundamental issues." I thought their approach to it, their approach of just looking at things from Oppenheimer's point of view, the balance between the personal and the global, felt really good. So it really gave me the confidence to sort of dive in. And then I looked beyond, when I went outside the book, guided by things in the book, I went to primary sources. So I went to the transcript of the security hearings, for example, and the record of the Senate confirmation hearings, things like that. So yeah, you don't want to feel paralyzed. You don't want to feel stifled by a sense of responsibility. I think you have to exercise that sense of responsibility in your choice of subject and your choice of approach, and then you have to just go for it.

'A snowballing effect'

Your films tend to ride like a cresting wave, and "Oppenheimer" is a shining example of it. You're just inexorably pulled towards that conclusion, towards that last scene. Is that a pace that you set for yourself right away on the page, or is it something you bring to the set, or is it something you just only get in post?

I think it's there at the very beginning as I write the script, and then it's there in post. Filming, you're sort of trying to give yourself the tools and you're mindful of it, but really you have to sort of forget about the mechanics when you're there with the actors on set. You have to let each scene breathe in the way that it should to have the reality and truth that it should have. And then you reimpose the mechanic in post, if you like. But the original conception ... I used to refer to it as a snowballing effect towards the last act, because you're trying to gather momentum more and more and more to lead to the end. That's a pacing and narrative technique I've used in a lot of different films in a lot of different genres, but the essential mechanic's the same. So it's there at the very beginning and I try to forget about those mechanics while shooting, and then it's there again at the end.

'There's always a reason that every one of these characters is there'

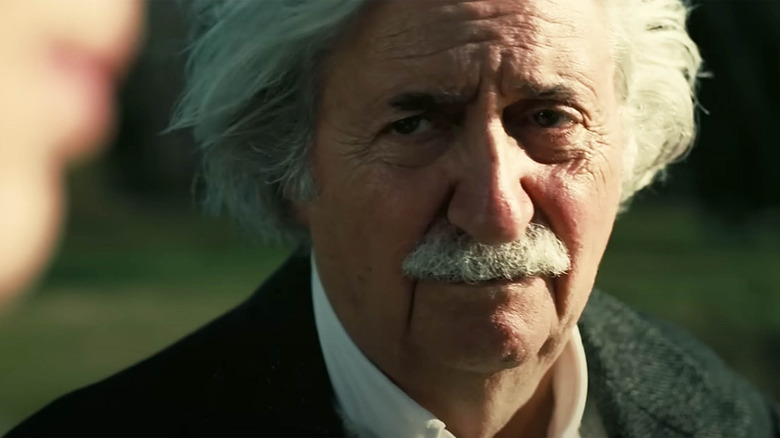

Much has been said and can still be said about this incredible cast, this ensemble, but one of the tenets of this movie is that it's got a moment for everyone to shine in it. Is that something you were cognizant of when you were writing the script initially? "Oh, I should give Bohr a little bit more here." Or was it something you found later?

I mean, I tried not to be too self-conscious about it, but when you're writing a multiplicity of characters and I didn't want to make composite characters, so then you're in a position of saying, "Well, why is this person in my script?" Well, Louis Alvarez is in there because he reproduced the experiment to split the atom, and I don't want to give that to someone else. And he ran out of the barbershop and he ran out as he did. I took the gamble that rather than create composite characters, just casting interesting actors, an Alex Wolff or Jack Quaid for these faces that you need to be there, that you'd remember those if you don't remember the names of who the scientists are. You're picking up on their particular energy and what they're bringing through threaded through the film.

And so I think naturally as I'm writing, the theatrical conceit, "Why is this character here?", that gives them a little moment. You know what I'm saying? You sort of feel that moment there. And I think certainly with Feynman, I think with Jack, he sort of grew a little bit in the making of the film, because of what this actor was able to bring in terms of their energy. So I knew there would be, for example, there was always a scene in the corridor of the T section when they're hearing the radio broadcast from Truman, but I didn't know which scientists [would be there] or how or whatever.

Then you get to the staging and realizing that we've seen Feynman in a couple key moments. He's somebody that we've seen a particular mood of, and we sort of see that mood shift. There's a wonderful very moving sort of little thing that he does there that's there in the film. So some of these moments are found with individuals just in the way it's filmed, but there's always a reason that every one of these characters is there, I suppose I would say.

'I think the relationship between film and time is exciting'

One of the things that moves me about your work over and over again is your seeming interest in time, and the way cinema has this ability to have an elasticity of time. And certainly in "Oppenheimer," you apply that technique to history. Is that elasticity of time something that draws you to cinema in particular as a medium? Is it something you really want to explore?

Yeah, I mean, it's interesting. I think the relationship between film and time is exciting, and it's one of the things that as you start to make films, you get excited about. I mean, I started with Super 8 film and splicing it together, and you're literally physically holding the timeline and watching it spool through [the projector], if not spooling it through yourself. So that part of it, and I think the elasticity that you refer to, it's very analogous to the flexibility of the screen itself. So the screen, the proscenium arch, the shape of the screen, the size of the screen, is irrelevant. You see through that screen and that screen could show you a massive landscape or it could show you a face or a tiny detail of something. That doesn't bother us in the slightest. We don't think of there being a physical size to the screen that's displaying the image.

It's very similar with time in film. It can be any timescale. So "Dunkirk," for example, we have three different timescales running against each other and then interacting, and that's using the elasticity of time that the cinema can provide. One of the interesting things about the relationship between movies and times, I think, is that — call it conventional films, romantic comedies, regular films — the use of time in those films is incredibly sophisticated and complex. All kinds of illusions, all kinds of different pacing, different jumps forward, but nobody thinks about it in a regular film. It just works. I make films where I draw attention to that mechanism, hopefully for dramatic effect. So in a way, my films, their approach to time is simpler than other films, but in being simpler and being exposed, it engages the audience with the mechanism of the film.

'I would never say never'

I'm a huge supporter and fan of physical media. I love that this 4K release of "Oppenheimer" sees you doing what you typically do on your home releases, with the shifting aspect ratios. My collecting your films goes all the way back to owning that "Memento" special edition DVD and trying to hear all the multiple endings of the commentary that you did. That was a beautiful moment in my dorm room in college. And on your special features, you are so erudite, you're so forthright with your process without totally giving up the ghost. Can we ever expect another commentary track from you in the future?

I find, actually, it's interesting — the tyranny of time as running through the projector, you never feel that more as a filmmaker than when they make you do a commentary track. Just trying to keep pace with the imagery, trying to say all the appropriate things as your movie unspools at 24 frames a second, until you get to an action scene or something. It's pretty punishing, and I've found it's not always the best way to approach the film itself. So we've taken different approaches over the years. This film has a more documentary approach to it.

I mean, I would never say never, but even when you do it, they tend to cut it together from multiple takes, because you lose sync with the material. Some of the earlier commentaries we tended to do as a scene by scene version, if you like, particular scenes we honed in on. They've tried a lot of different things over the years with approaches to the behind the scenes material. But there is something about the commentaries, because they run in sync with the films, which makes them difficult. But it does mean that they tend to have more of a life, because they get stuck on an extra audio track in different subsequent releases. So unfortunately, with the "Memento" one that you referred to, I think they literally [went] with one ending [on subsequent releases]. So my whole thing about not having a definitive ending [to the commentary] kind of bit me when they started just dropping the other two endings but, you know. [laughs]

"Oppenheimer" will be available on 4K Ultra HD, Blu-Ray, and Digital starting November 21, 2023.