Ludwig Göransson Crafted The Oppenheimer Score Through Emotion And Experimentation [Exclusive Interview]

There are two general schools of thought when it comes to composing music for films. One says that the music should be completely its own thing, an artistic work in its own right that's inspired by the characters and material in the movie it's for, and whether it's scene-specific or not doesn't matter. The other says that the score should be somewhat invisible, there in the background of the movie only to support the emotion that's occurring on screen, something that should not stand out and take over.

Like any schools of thought, rules, guidelines, and the like, the real innovation and magic only comes when such things are bent or broken. Composer Ludwig Göransson has been breaking new ground with his TV and film scores since 2009, when he brought a surprising sonic and emotional range of music to the similarly innovative sitcom "Community." Ever since then, he's gone on to do such things as win the Academy Award for his work on Ryan Coogler's "Black Panther," lend a distinctive sound to the "Star Wars" spin-off series "The Mandalorian," and collaborate with Christopher Nolan on "Tenet."

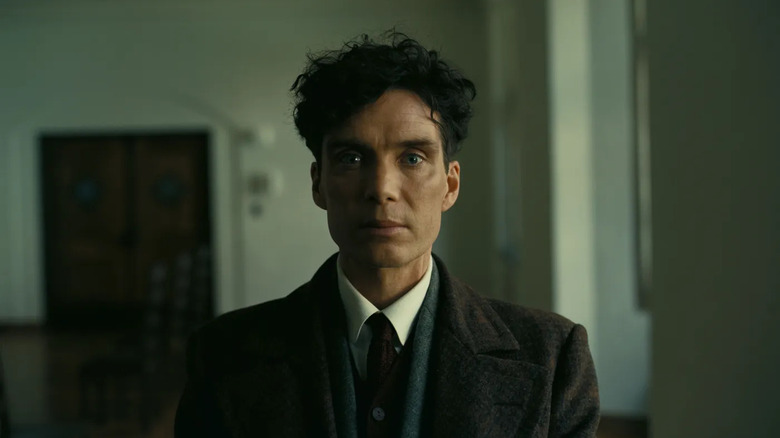

That collaboration continued with this year's "Oppenheimer," and for Nolan's ambitious, experimental, incredibly taut and tense film about the father of the atomic bomb, Göransson created a score that encapsulates all of that emotion, ambition, and more. I had the opportunity to speak with the composer on the eve of the film's physical and digital release, and he told me about how he constructed his sonic palette for the film, how experimentation leads him through his work, and that there may indeed be an expanded soundtrack release of the score on the horizon.

Note: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

'The only feedback Chris gave me in the beginning was to use the violin to embody Oppenheimer's personality'

This film has such a wealth of material in it: the historical events, the huge ensemble of characters, the subjective POV, the political repercussions. Yet it's one of the most propulsive movies ever made, and your score's such a big part of that. How did you establish that pace? I know you wrote a lot of your score before you ever saw a frame, but was it a push and pull with how you saw some of the edit come together? Or was it something that you had in your mind right away from when you first started working? How did that come about?

No, I would say it came about through a lot of experimentation, and also early on after reading the script, understanding that the music needs to put the audience — I mean, the script put myself, when I read it, into Oppenheimer's shoes, and I was feeling what he was feeling, I was seeing what he was seeing, and the music needed to do the same. And the first two months after reading the script I spent with Chris Nolan — this is pre-production, before he started. So I had one meeting every week and I'd write music and we'd meet up and we'd talk about it and we'd listen to it together and we'd go through the details of the cues, listen to certain sounds, listen to certain themes.

The only feedback Chris gave me in the beginning was to use the violin to embody Oppenheimer's personality, because the violin is a fretless instrument, so you can go from something beautiful and intimate and romantic, to something horrific and neurotic within a split second, depending on the vibrato or the intensity of glissando up and down. So that's how we built the song world, just using that instrument, experimenting, and throwing almost anything at the wall and see what stuck.

'This is pretty special'

Were there any particular influences for you going into this musically, from any facet of music? Was there anything you were trying to steer away from or emulate?

No, the only musical input that was in the script was in the first montage when he listens to The Rite of Spring, [Oppenheimer] put on that record. That was not very kind of Chris to put the bar that high. [laughs] Obviously, I'm not going to be able to write anything better than Rite of Spring. But it was interesting because he really helped putting me into the brain and the musical ideas of what Oppenheimer was listening to at the time.

But otherwise, my wife, Serena, she's an accomplished violinist, so we were sitting down the first couple of days just recording microtonal glissandos up and down, trying to sound almost like making sirens. Remember those 1950s black and white commercials when they have those siren tests, nuclear reactor –

Air raids, yeah.

Air raids, where you see the kids hiding under a table. "This is what you're going to do." But trying to create some sort of air raid and then a whole day went by and we're creating those glissandos and making tracks and stacking them on top of each other. We were really tired and we were just about to wrap, and then I got an idea with a super simple melody, and I brought a bassline to it and Serena performed it in such a beautiful, intimate way with a really fragile tone, no vibrato. And we recorded it and I knew immediately, "This is pretty special." And I sent it to Chris and he called me 10 minutes later and was like, "This is it." Then you hear that constantly through the movie, different iterations.

'I always want to use new methods to find my way and to get inspired'

When you're composing a score for a film, what is the first thing that motivates you? Is it a sonic palette that you want to create, sort of a "put all your paintbrushes down" sort of thing? Or is it a theme that can key you in and then you go from there? Do you have a typical way of working, or is it different every time?

It's always different. I'm always trying to make it feel like I'm doing something new, I'm doing something for the first time. I always want to use new methods to find my way and to get inspired. And with "Oppenheimer," I knew that the most important part of the music was going to be through its emotional core. So I didn't want to start with sounds. I didn't want to start with production. I didn't want to start hiding behind technology or sound manipulation. I really wanted to get out with the emotional, with the theme, with the melodies first, just with the solo violin. And I knew if we got that right, it would be easier to get that then the synths and the manipulation and the strangeness, and the production would be easier after if we got the emotional core right first.

There's a propulsiveness to your work that I find so invigorating, and really, it's like a cresting wave that you're riding throughout the movie. You're always carried by it, as well as emotionally involved and getting the characters and being in their world. Is that a focus for you, or is it something that just sort of happens naturally in your process?

I think it's both, but I'm not constantly thinking about it as I'm doing it. That was something that was interesting with "Oppenheimer," emotionally, I wasn't thinking about it as I was doing it. And it's not until later, like now, like a year later, when I'm reflecting over the process and reflecting over how these themes came about and thinking about some of the places I had to go emotionally to be able to put that music in his feelings was pretty dark at times. And it's not until now, a lot later, where you're able to reflect with that.

'Oh my God, there's so much material'

When I read about your process of creating this score in terms of writing it, I saw you made suites, or at least large swaths of material, before ever seeing the footage. Does that mean there were a lot of ideas or even motifs or themes or material that didn't end up in the film?

Yeah, there were a lot of things that I think some of it didn't end up in the film, but there's about 2 hours and 40 minutes of music in the film. So we tried out a lot of things. In the beginning, we just threw everything at the wall when I was just experimenting. But most of it, the larger pieces and the big DNA of the score was created in the beginning. So when Chris has the first cut and he sits down with Jennifer Lame and they take all that music and put it into their first cut and they do a really great job together, just road-mapping out some of the core of the score using the music that we've already written. But then obviously there's a bunch of stuff missing. So that's really when my job really starts.

Do you think there might ever in the future be an expanded version of the soundtrack with more of this material?

I remember we talked about that when we started making the score. Chris is also very active when we put the score together. We were like, "Okay, we'll make it 60 or 90 minutes long." And then we started going through all the music and we're like, "Oh my God, there's so much material and we're not really repeating a lot." There's a lot of new information, there's a lot of themes, different themes, different feelings, and we wanted to get that all on the soundtrack. So the soundtrack is pretty long, but eventually there might be something coming out. I don't know.

"Oppenheimer" will be available on 4K Ultra HD, Blu-ray, and Digital on November 21, 2023.