Skinamarink Is An Early Contender For The Scariest Horror Movie Of 2023

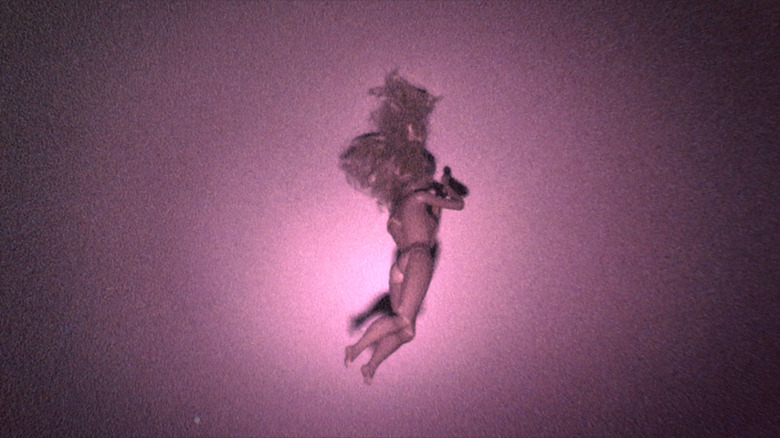

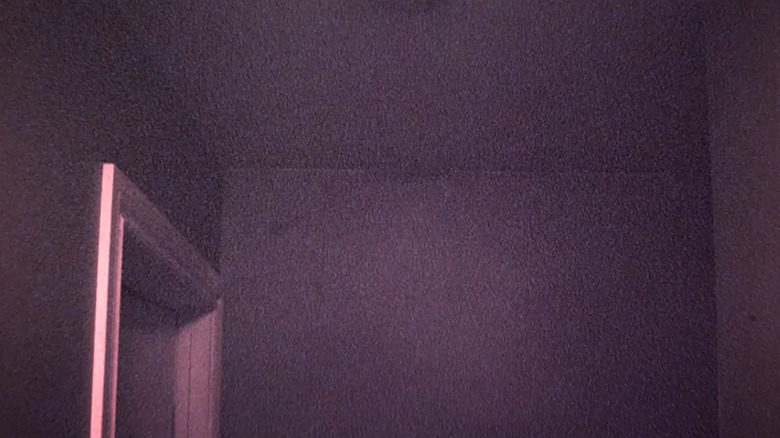

Kyle Edward Ball's experimental horror movie "Skinamarink" demands patience. Filmed in the director's childhood home in Edmonton, "Skinamarink" is about a pair of children, only four and six, who creep around their house to find that its doors and windows have vanished. Their father also appears to be missing. The rooms are lit only by the flickering cathode ray tube TV, constantly broadcasting public domain cartoons, offering no distraction. The audience rarely sees the children's faces, and no one can speak above a whisper. The cinematography, by Jamie McRae, is scratched and grainy, and the audience is often entreated to peer — for minutes at a time — into the blackened, writhing abyss of an empty, empty hallway. The film's soundtrack features the kinds of shifts and thumps one might hear from another room, carried along by a terrifying, pervasive white noise that seems to get louder as the film progresses. It becomes clear after a while that there is indeed someone ... or something ... in the house with the children.

There is no plot, as such, although there is a steady progression of events. Key lines of dialogue reveal new nightmare scenarios unexpectedly unfolding in the dark. When the four-year-old boy Kevin (Lucan Paul) calls 9-1-1, we can't really hear his voice, and the operator's dialogue is subtitles. You cut yourself and now you feel sick? What is happening?

If one can push through the film's slow pace and quotidian setting, one might find one of the most terrifying cinematic experiences in many years. Ball has tapped into something recognizably primal with "Skinamarink." He delves deep into the recesses of a suburban kid's childhood mind, dredging up long-forgotten fears and nightmares. "Skinamarink" recalls a time in one's early years when 3 a.m. didn't exist.

Your childhood nightmares, captured

Prior to "Skinamarink," Ball ran a YouTube channel called Bitesized Nightmares, wherein viewers would write in describing their scariest dreams, and Ball would adapt them to film. In many of the letters, viewers described the common dreamed childhood experience of waking up in your own home, but finding it twisted in some way. The hallways no longer lead anywhere, or there are stairs leading to rooms that weren't there before. Many described absent parents, or being alone as a kid. Ball distilled these real-life nightmares into what might be the most accurate, uncut fright experience seen since the days of David Lynch's "Eraserhead." Lynch's 1977 film was also notoriously slow-paced, and also seemed to take place within a nightmare. "Eraserhead," however, did have scenes of dialogue and incident. "Skinamarink" is a more abstract experience. It does away with the pesky constructs of plot, character, and other such useless fineries of screenwriting 101. It delivers, instead, fear unadulterated.

Comparisons could be made to Daniel Myrick's and Eduardo Sánchez's 1999 film "The Blair Witch Project." That film was shot largely on tape, and followed a trio of filmmakers through the woods of Maryland. Despite maps, they still got lost, and were hounded by strange noises and physical encounters at night. Was there a witch in the woods? "Project" caused a sensation in 1999, and famously made about $250 million worldwide on a scat $200,000 budget. After watching it, many had trouble sleeping.

Ball, in shooting in his own childhood home, involving scant actors, and editing himself, was able to construct "Skinamarink" for a mere $15,000 (Canadian). In the United States, that's about the price of a 2014 Volkswagen Jetta with 150k miles on it.

After watching it, I had trouble sleeping.

Bear with it

Like "Project," "Skinamarink" is a difficult film to sell. It's lo-fi filmmaking, slow pace, and Jungian imagery are certainly terrifying, but it may still repel audiences in the mood for action, mayhem, blood, and jump scares. This author is old enough to recall the backlash that arouse after the explosion of popularity experienced by "The Blair Witch Project." Rowdy young audiences, hearing that it was the scariest film of all time, were disappointed to find a distinct lack of "oogity boogity" style scares. One can immediately sense an already-incoming backlash on "Skinamarink" as well. It's not a film that leads audiences through a story, but lets them drift through an experience. Long, long half-visible sequences lead children into their parents' bedroom where a disembodied voice whispers "look under the bed ..." Or a mom, motionless and facing the wall, merely whispers "Kaylee, I need you to close your eyes."

These whispered incantations are the "payoffs" in "Skinamarink." If you can get onto the film's surreal wavelength, those moments will penetrate deep into your brain. You will not jump out of your seat. You will be pressed into it.

A few years ago, audiences flocked to see a pair horror movies about a killer sewer clown that ate children. These were the two chapters of "It," based on a novel by Stephen King. The two "It" movies were constructed like thrill rides, presenting childhood fears like bloody, noisy amusement part attractions. Those movies were better watched in large groups, with whole audiences shrieking in unison, and then laughing as the fear dissipates.

"Skinamarink" may be best alone at night with the lights out. You must do the work. You must push yourself into the film grain to see the nightmares shimmering inside. You may also find a profound terror experience.