American Fiction Review: A Dizzyingly Funny Literary Satire Featuring A Never Better Jeffrey Wright [Austin Film Festival]

The relationship between art and commerce has always been a prickly one for creative people. Making a living — a good living — in an artistic field requires skill and talent, yes, but it more often than not also requires the artist to tailor their work to popular trends or to stifle one's own thornier aspects to satisfy a mass audience. Now, when I say "mass audience," what this invariably means is a mass white audience. Just as heterosexual people are seen as the baseline norm of the sexual spectrum, white people are seen as the baseline norm when it comes to cultural consumption. For a piece of art to be considered widely successful, it is that white audience that movie studios, record labels, and book publishers so desperately want, and anything beyond that is basically just thought of as found money.

For Black artists, connecting with that lucrative audience poses even more challenges. Just as white people are seen as the baseline for the populous, they are also seen that way for artists. A Black artist isn't an artist. They are a Black artist, and every piece of work they create will be looked at through the lens of how it reflects the Black experience, even if the intention behind the work has next to nothing to do with the Black experience. And, of course, that lens isn't actually the Black experience. It's white people's idea of the Black experience. So, if you want to be a successful Black artist, how do you reckon with wanting to express yourself creatively when the best course of action for financial prosperity is to pander to what those white people expect of you?

This is the dilemma at the heart of Cord Jefferson's sterling feature directorial debut "American Fiction." Reading that layout of the themes, you might be under the impression that this film would be some dry academic exercise of naval gazing about art, but that couldn't be further from the truth. "American Fiction" is a rollicking satire of commercial artistic enterprises that stands joke-for-joke against any of the best comedies in the last five years.

Tipping the scales of reality ever so slightly

Thelonious "Monk" Ellison (Jeffrey Wright) works as a literary professor in Los Angeles and has managed to publish several acclaimed books over his career, though no one would call him a major commercial success. His work would fit far more aptly in the "Mythology" section of Barnes & Noble than the "African-American Studies" section, though the bookseller categorization would never give him that credit, much to his chagrin. His agent (John Ortiz) struggles to shop his new book around to publishers because the work doesn't fall into one of those predetermined boxes for Black voices.

Monk finds himself returning to his hometown of Boston, and his life gets turned completely upside-down when he learns that his mother (Leslie Uggams) has Alzheimer's and requires constant — and expensive — care. Partly as a joke and partly inspired by the work of author Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), whose latest novel "We's Lives in Da Ghetto" has become a bestseller, Monk assumes the pseudonym of on-the-lamb convict Stagg R. Leigh and writes the most pandering, stereotypical "Black" novel he can imagine called "My Pafology," complete with gangsters, murder, cops, a tragic father-son dynamic, and over the top, phonetically written dialogue. It immediately becomes a sensation.

What makes the satirical bent of "American Fiction" so impactful is that it isn't a complete cartoon interpretation of the literary world. Cord Jefferson firmly places this film in the real world but just turns the notch on the outrageousness knob about 10-15 percent. The more real the obliviousness of the white publishers (Miriam Shor and Michael Cyril Creighton) or the white filmmaker (Adam Brody) who wants to adapt the novel for an awards-bait movie feels, the harder the laughs are. To some, the tropes are all too recognizable, and all we need is that slight adjustment for the jokes to land. For those who don't realize how much their vision of Black artists lines up with the white people in the film, this could serve to be a rather eye-opening experience that hopefully allows them to realize they are laughing at themselves.

The comedy isn't entirely confined to the artistic world. Monk and his family, which includes the likes of Tracee Ellis Ross and Sterling K. Brown, are all smart, passionate people who don't mince words when it comes to trading witty barbs with one another, and Jefferson isn't afraid to let his characters go to dark places for the humor, either. They don't have what you would call a close family, but any family has its special brand of camaraderie that allows for unexpected relationships to mine for both comedy and drama.

Not drowning out the pathos

The other important reason "American Fiction" doesn't exist in its own fanciful universe is because that would very easily render much of the human drama far less effective than it is. The literary world only makes up about half of the film, as this is also a proper character portrait of Monk as a man. His mother's Alzheimer's diagnosis isn't just a financial burden on him, but an emotional one as well. Compounding things, he is dealing with a recent death in the family as well as the suicide of his father, with whom he was the closest, several years before the film's beginning. Monk operates in a very solitary fashion, keeping people at an arm's length at a minimum, and his closed-off nature can be quite the turn-off for people who just want to accept and love him. Juxtaposing the pitch-perfect laughs with proper character drama makes "American Fiction" a far richer experience, not just emotionally but also in demonstrating all the different facets of what makes a Black artist.

The one area I have to ding "American Fiction," though, comes from this more serious side. While caring for his mother, Monk strikes up a relationship with their neighbor Coraline (Erika Alexander). She and Jeffrey Wright have a lovely chemistry, and seeing a courtship between two people in their 50s on screen is such a rarity when it really shouldn't be. Coraline reveals to Monk that she has read some of his books and particularly admires how he writes female characters. But I don't think the same can be said for this character. She isn't poorly written, exactly. Coraline just falls into the unfortunate space of being "the girlfriend," who is basically only there to emotionally open up the protagonist. We get so little sense of what her life is like when she's not sharing a space with Monk. This pretty archetypal character in a pretty archetypal relationship does set up one of the best jokes of the whole film towards the end, but nothing about how the rest of that story is played makes us think it is anything other than entirely sincere. With most films with this type of character, you'd simply shrug and begrudgingly accept the rote nature of it, but "American Fiction" directly calls out the strength of female characters through the voice of someone who isn't living up to that strength. It's a rare false note in a movie that otherwise has such a firm grasp on its tone, characters, and themes.

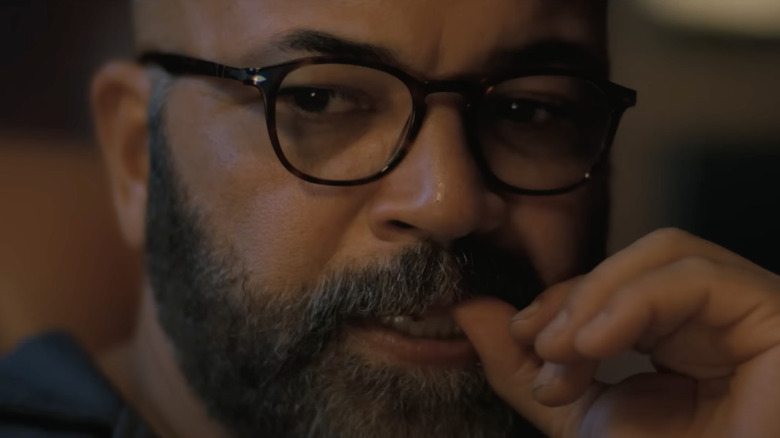

The magic of Jeffrey Wright

At the center of all of this is Jeffrey Wright. As a character actor obsessive, I always long for movies where performers I love so dearly are given opportunities to be the focal point of the story. This isn't the first time Wright has been able to lead a picture, but I believe it to be the greatest work he's ever done on film. The idea of a totemic film performance usually amounts to showy pyrotechnics and full body transformation, both of which Wright is fully capable of delivering. Monk doesn't require any of that. Instead, the power and joy of his work here is in confinement.

Monk is a challenging figure. Though he has a valid point about Black people's place within the artistic community, he is also unquestionably a condescending elitist that would make people who agree with his worldview steer clear of him. The film even opens with him being placed on mandatory leave from his teaching job for upsetting a white female student who is uncomfortable with a certain word in the title of Flannery O'Connor's short story "The Artificial N*****." Monk doesn't suffer fools and isn't interested in making friends. Wright could simply make a man like that repellent or charmingly grouchy, which would be a familiar type of cinematic author. What Wright aims for instead is someone aware of how he turns people away even while his nature cannot help him from doing so. Deep down, he clearly wants to establish connections with people, but his brain always makes second guesses, assuming the worst of people even in their most helpful state.

Making the performance even more extraordinary is Wright's ability to precisely nail every single gag in the picture. Sometimes that means putting on the voice and demeanor of his newfound Stagg R. Leigh persona to convince others what a hardened criminal he is, or it could also just be a completely silent look of him realizing a relationship between two people. Both ends of the spectrum had me howling, and without someone as skilled as Jeffrey Wright in that position, I don't know how effectively those jokes land, either because they'd be overplayed too much or way too underplayed.

Though he has long been a television writer on shows ranging from "The Good Place" to "Watchmen," directing a feature film is another beast entirely, and Cord Jefferson establishes himself as a filmmaker with a lot to say and a unique way of saying it. Tackling such big ideas with a film that tonally switches back and forth between wacky comedy and heartfelt drama would be the death knell for so many first-time directors, but Jefferson, Wright, and every single craftsperson who worked on the film have such a firm grasp on the story being told that the result is one of the more joyous experiences I've had in a theater this year. "American Fiction" fully understands that you don't have to sacrifice art or politics for entertainment, satisfying those who want a rich thematic experience or to just have a laugh in a crowded theater.

/Film Rating: 8.5 out of 10